Science is awesome. And, as we all already know, so are Jewish women. Thus brings me to the question: Why not combine both? Luckily for us and the entire world, there is no shortage of amazingly inspirational female Jewish scientists—you just may not have heard of them yet.

We can all be inspired by these intelligent, glass ceiling-breaking, status quo-pushing, and society-changing Jewish women. After all, to be Jewish is to persevere.

In no particular order, the following are five Jewish female scientists you should know:

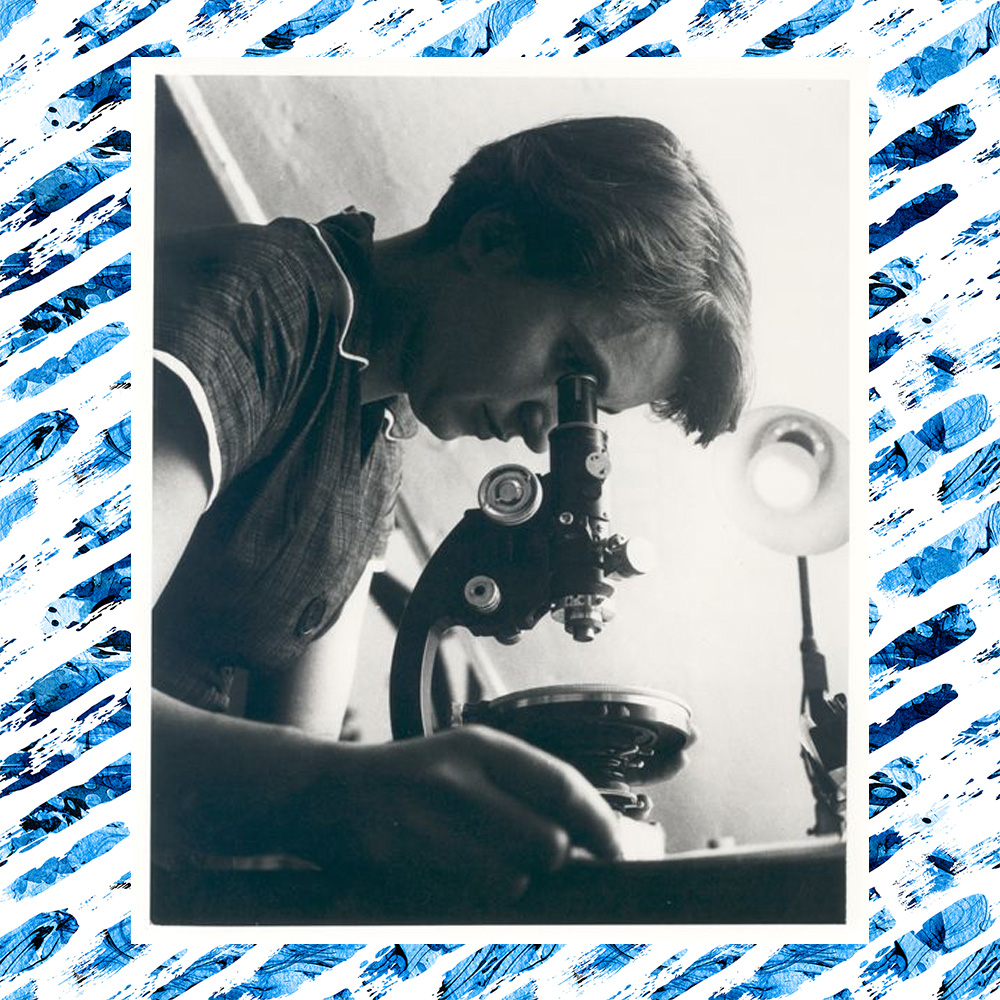

1. Rosalind Franklin

You may remember Rosalind Franklin for her unfairly cast secondary role in your high school biology curriculum. (Or is that just me?)

Rosalind Franklin was born to a prominent Jewish family in London, England in 1920. Her family helped settle Jewish refugees during World War II—even taking in young children from Kindertransport to live with them. Franklin was an agnostic; she once even said as a child to her mother regarding God, “Well, anyhow, how do you know He isn’t She?” (the O.G. Ariana Grande’s “God is a woman”). Yet, she remained culturally Jewish and was “always consciously a Jew.”

Franklin attended Cambridge and graduated in 1941, and eventually completed a PhD there in 1945. She then went to Paris, where she learned X-ray crystallography techniques, which she later used to study DNA. Franklin and her research partner, Raymond Gosling, discovered two forms of DNA, A and B, and found that both types were helical. Meanwhile, there was a major competition to discover the structure of DNA.

James Watson—who is credited with discovering the DNA structure with his partner Francis Crick—attended a lecture given by Franklin in late 1951, where she revealed key details about DNA. But, Watson failed to pay attention and created an inaccurate model in his notes. Watson later sought out Franklin in 1953, but proceeded to insult her by suggesting that she did not know her own work. The audacity!

References to Franklin in Watson’s book The Double Helix are overshadowed by his critiques of her (like calling her unattractive and aggressive while referring to her with the diminutive “Rosy” against her spoken dislike). Eventually, Crick, Watson, and Wilkins won the Nobel Prize in 1962—with Franklin’s contribution completely overlooked.

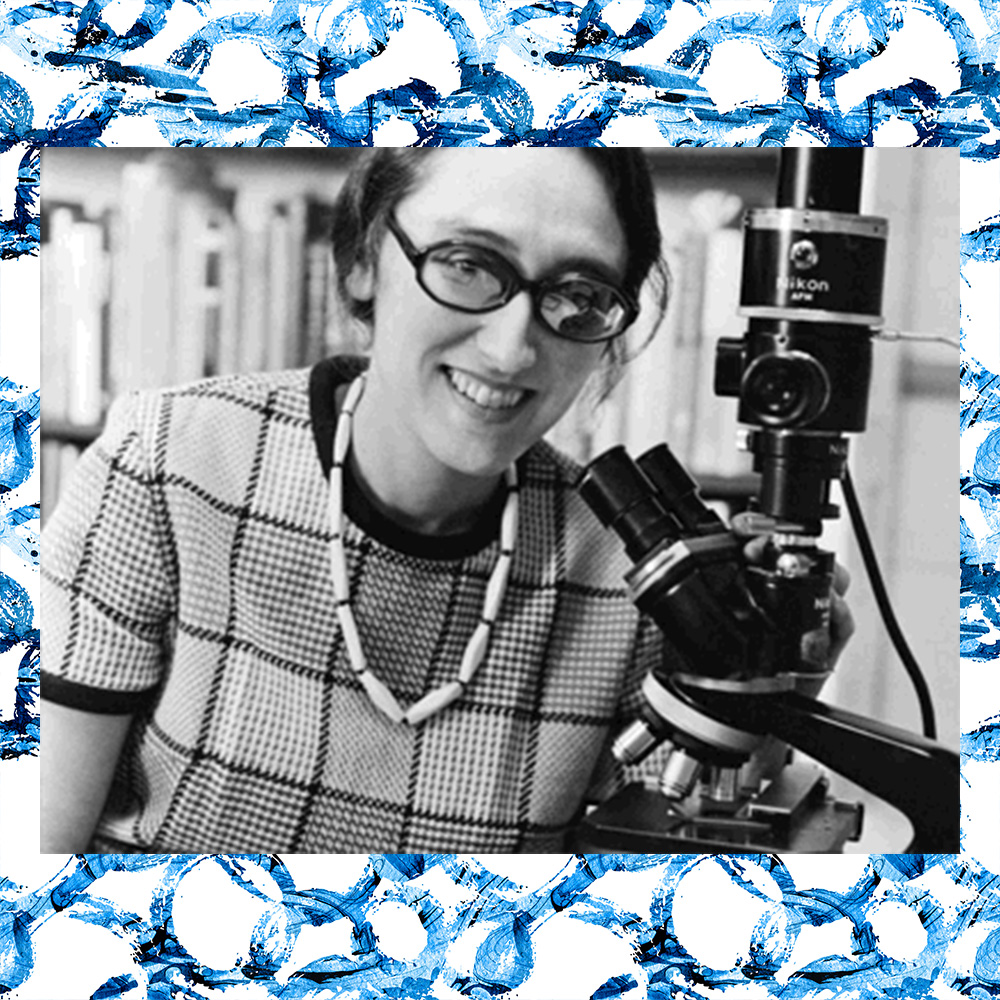

2. Lynn Margulis

Lynn Margulis (née Alexander) was born in Chicago in 1938 to a Jewish family. At only 19, she earned a BA from the University of Chicago and followed this with a master’s in genetics and zoology (at only 22!). But she didn’t stop there; Margulis obtained her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1965.

Margulis furthered something called endosymbiotic theory, but her findings were “rejected by about fifteen scientific journals.” She was even told, “Your research is crap, do not bother to apply again.” Without getting bogged down in the nitty gritty, the basis of her theory was that eukaryotic (read: animals, plants, fungi, etc.) cells originated and evolved from prokaryotic (mostly bacterial) cells. The scientific community rejected her theory up until the 1980s because it questioned Neo-Darwinism and how we understand evolution. Yet, it has since become widely used in biology education.

She passed away in 2011 at the age of 73. Even in death, her theory lives on; Margulis was a radical, rebellious iconoclast for her continued belief in her theory and resistance to the scientific status quo.

3. Mathilde Krim

Mathilde Krim (née Galland) was born to a Catholic mother and Protestant father in Cumo, Italy in 1926. In 1945, horrified by the Nazi terrors, she became active in Zionist causes—helping smuggle guns to British Mandatory Palestine. She converted to Judaism before marrying an Israeli man, Avid Danon, in 1948. (They moved to Israel shortly afterwards, and their marriage would end in divorce.)

In 1953, Krim earned a Biology PhD from the University of Geneva, specializing in viruses. In Israel, working at the Weizmann Institute of Science, she pioneered tests for prenatal determination of sex (so I guess we have her to blame for those gender reveal parties).

In 1958, she married entertainment lawyer and political adviser Arthur B. Krim, and she dedicated herself to civil rights, gay rights, and the independence of Rhodesia and South Africa. With the onset of the AIDS crisis in 1981, she studied the disease and raised awareness, and founded the American Foundation for AIDS Research with (fellow Jew!) Elizabeth Taylor. She continued her activist work until her death in January 2018, at age 91.

4. Bessie Moses

In 1893, Bessie Moses was born to a Jewish family in Baltimore. She graduated from Johns Hopkins Medical School in 1922. She initially worked as an obstetrician (a doctor, who specializes in pregnancy and childbirth), but became a gynecologist after she got too attached to the babies (awww). In 1927, she opened the Baltimore Birth Control Clinic. They provided contraceptives, but in order to oblige with strict laws and societal norms, women were only able to seek treatment if they were married and if a future pregnancy would likely prove to be fatal.

Over time, her organization was absorbed into Planned Parenthood.

Moses worked to reduce stigma about using birth control by providing resources on their use and administration (including to medical schools) and fighting against the illegality of sending contraceptive information via mail. Her legacy lies in our ability to obtain birth control today.

5. Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini was a Sephardic Jew born in 1909 in Turin, Italy. Her father initially did not support Rita and her sisters’ academic pursuits; yet, Levi-Montalcini eventually attended medical school.

Her professional research was sort of halted in 1938 when Mussolini’s laws banned her and other Jews from working. But that did not stop her: She proceeded to secretly conduct research. Following the Nazi invasion of Italy in 1943, she and her family fled to Florence and hid with the help of non-Jewish friends. Her family survived, returned to Turin, and she eventually split her time between the U.S. and Italy.

Her research during this tumultuous time was re-conducted and replicated; she discovered nerve growth factor (the protein that causes the production of nerve tissue), which earned her the medical Nobel Prize in 1986.

Rita never married or had children; she remained active in science until her death at 103 years old, on December 30th 2012.

Rita Levi-Montalcini is my personal hero; as a Sephardic Jew of Italian origin, it means the world to see someone like me having a huge impact on the field I plan on pursuing.

I hope we all can channel not just all of these scientists’ general badassery, but the pure, unadulterated joy of Rita Levi-Montalcini, celebrating being the first female Nobel Laureate to reach 100 years old.

L’chaim!