Twenty-eight percent of Nobel Prize winners in Physiology or Medicine have been Jewish, with many female recipients serving as leaders in fields including neurobiology, pharmacy, and biochemistry. The stories of pioneering female doctors are always inspiring, but especially in a time when medical professionals are at the forefront of confronting a global health crisis.

1. Rita Sapiro Finkler (1888-1968)

Ukrainian-born endocrinologist Rita Sapiro Finkler devoted much of her clinical research to women’s health and helped female doctors impacted by World War II come to the United States. At age 16, she began studying law at St. Petersburg University, but decided to leave Europe and ended up settling in Pennsylvania. She was the first female intern at Philadelphia Polyclinic, although she still faced discrimination. Even after becoming an established doctor, she lost jobs after employers learned of her gender.

While Finkler originally studied pediatrics and obstetrics, she was drawn to endocrinology, a new field at the time. After returning to Europe, she helped develop the Aschheim-Zondek Reaction to detect early pregnancies. She advocated for women in her practice, researching topics like fertility issues caused by malnutrition during World War II and through her involvement with the American Medical Women’s Association. An avid traveler and photographer, she also spoke six languages.

2. Gerty Theresa Cori (1896-1957)

For her research on carbohydrate metabolism, biochemist Gerty Cori became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Born in Prague, Cori met her husband and research collaborator Carl Ferdinand Cori in medical school at the University of Prague. After moving to the United States because of growing anti-Semitism in Europe, she faced difficulties obtaining research positions, despite her husband’s persistence that they work together. They eventually were hired at Washington University in St. Louis, although she made one tenth of his salary.

There, they created the Cori cycle, which explains how lactic acid formed in muscles is converted into glucose. In 1947, they received the Nobel Prize along with Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay. This research on metabolic function had implications for aiding those with diabetes and other metabolism-related diseases. In her life, Cori was the fourth women elected to the National Academy of Sciences and was appointed to the National Science Foundation by President Harry S. Truman.

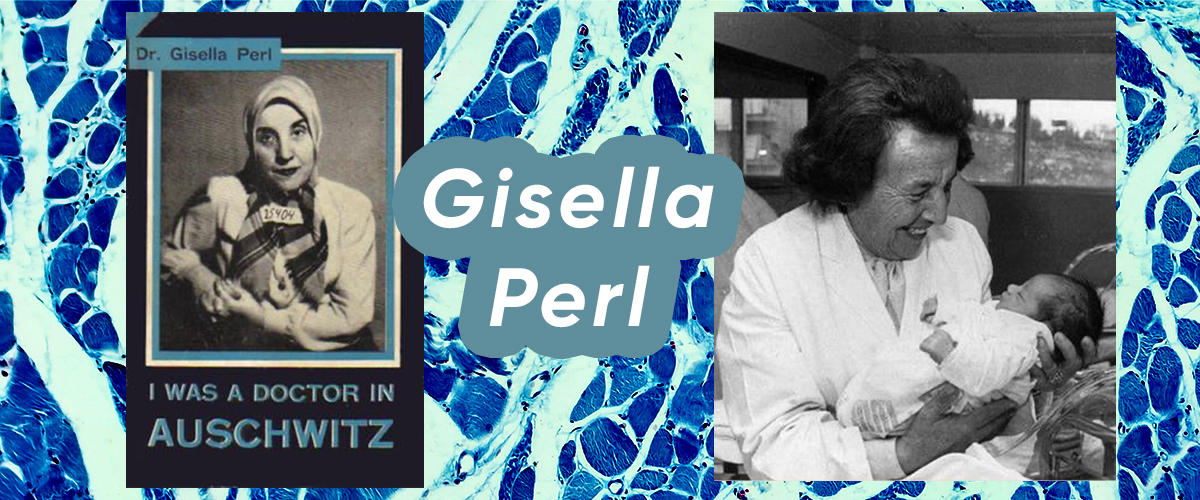

3. Gisella Perl (1907-1988)

After deported to Auschwitz in 1944, Romanian gynecologist Gisella Perl provided life-saving health care to hundreds of women. Perl had to convince her father to let her attend medical school. She was living in a ghetto when her family was sent to the largest Nazi concentration camp. While she helped others dealing with a variety of injuries and maladies, her most important work was conducting abortions, particularly for women who had been raped in the camp. Knowing that these women would be killed if their pregnant status was uncovered, Perl performed these procedures in the middle of night with no medical equipment.

Perl was the only member of her family to survive the Holocaust and attempted suicide in 1947, but dedicated the rest of her life to overcoming her trauma. She came to the United States and became an advocate for Holocaust remembrance. Her 1948 book, I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz, was one of the first texts documenting the sexual violence that occurred there. Although she had stopped practicing medicine, Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt convinced Perl to return. She focused on infertility, and during her career delivered around 3,000 babies.

4. Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909-2012)

Italian neurobiologist Rita Levi-Montalcini was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and even found ways to continue her research during World War II. Born to an engineer father and an artist mother, Levi-Montalcini had to push to study medicine at the University of Turin. Her professional options were limited because of race laws, leading her to pursue neurological research in Belgium. After returning to Italy, she built a lab in her parents’ home and studied the nervous systems of chicken embryos. Even when Turin was bombed, she continued this research, asking farmers for fertilized eggs.

She later worked in an Allied displaced persons camp before moving to the United States and focusing on neurobiology and cancer cell research at Washington University in St. Louis. She was awarded the Nobel Prize for discovering the nerve growth factor and increasing understanding of how cells divide to create new cells. A fun fact? She was the first Nobel Laureate to reach the age of 100.

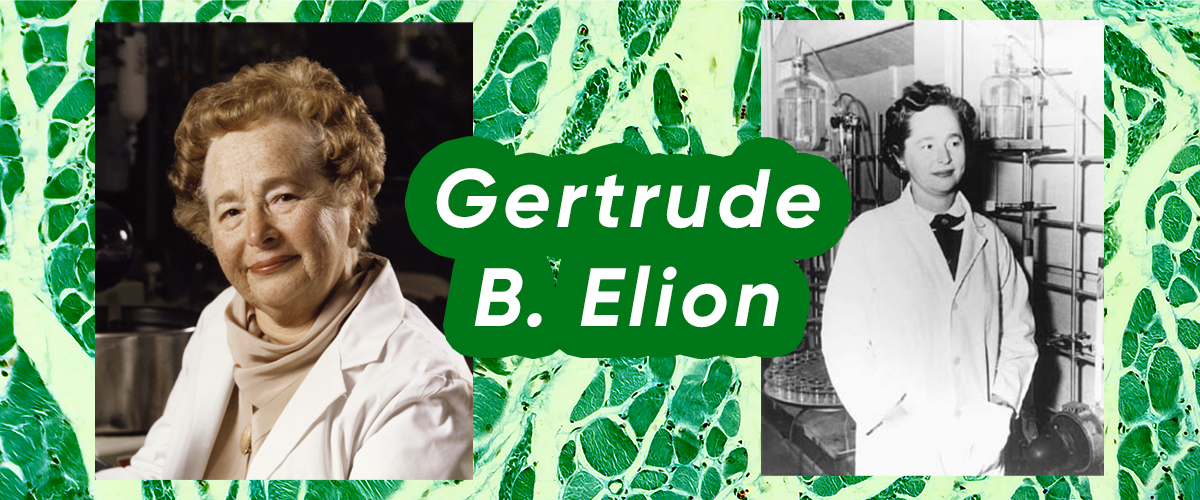

5. Gertrude B. Elion (1918-1999)

Gertrude Elion’s pharmaceutical research earned her a 1988 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine and 20 honorary doctoral degrees. The daughter of Lithuanian immigrants, Elion came from a long rabbinical tradition and graduated high school at age 15. After her grandfather died of stomach cancer, she was drawn to chemistry. She struggled to be taken seriously in her field, but found more opportunities working for pharmaceutical companies when many of her male peers left to fight in the war.

Her research focused on exploiting the biochemical divergences between normal cells and those causing viruses and cancers. Her work on what became known as rational drug design led to the development of medications, including the first successful antiviral and immunosuppressive drugs and AZT to prevent and treat AIDS.

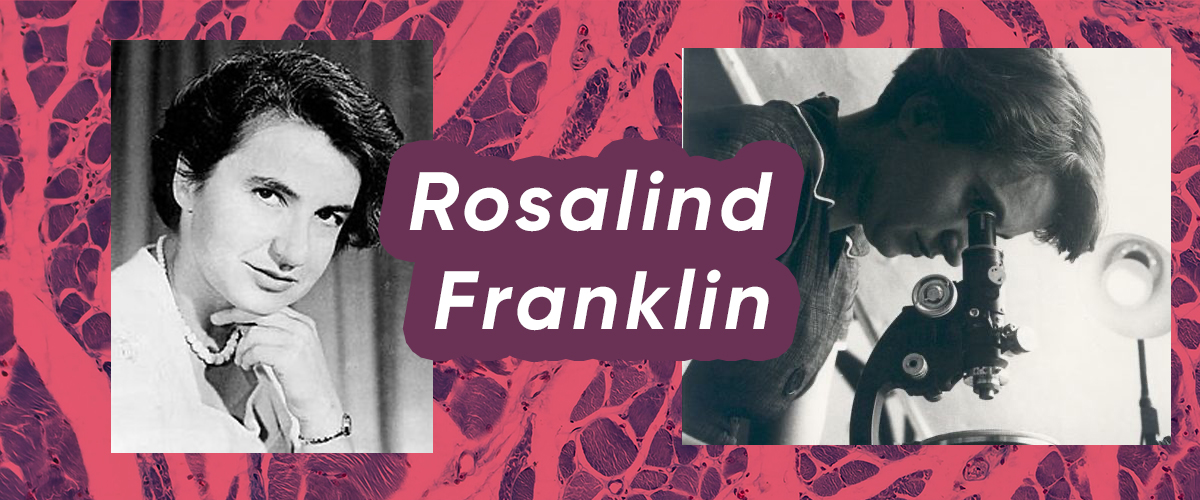

6. Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958)

Although Rosalind Franklin played a crucial role in mapping the structure of DNA, her contribution was largely ignored as credit was given to James Watson, Frances Crick, and Maurice Wilkins. At age 15, Franklin already knew she wanted to become a scientist. She studied at the University of Cambridge and became an X-ray crystallographer. As a research associate at King’s College London, she worked on X-ray diffraction studies.

Her images, particularly Photo 51, guided Watson and Crick’s discovery of DNA’s double helix structure — but she was not given proper attribution in their articles. After leaving King’s College London, she researched the structure of RNA and viruses as well as the changes that took place when coal was converted to graphite. Sadly, she died of ovarian cancer at age 37. It was not until the 1990s that her groundbreaking work was more widely recognized.

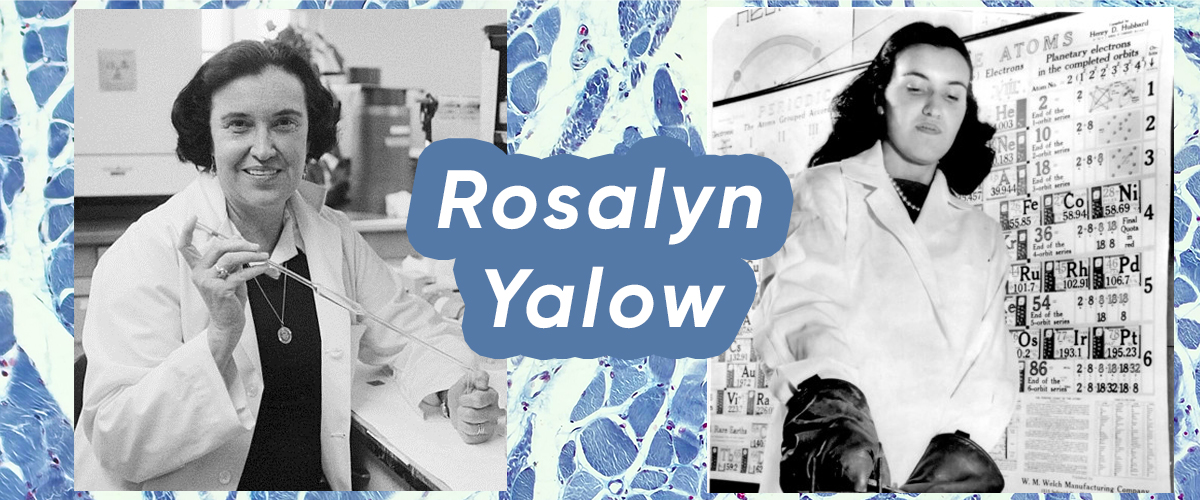

7. Rosalyn Yalow (1921-2011)

Nobel Prize winner and nuclear physicist Rosalyn Yalow developed radioimmunoassay to measure substance concentrations in the body. Coming from a working-class family in the Bronx, Yalow was inspired by Marie Curie and studied at Hunter College. She met her future husband Aaron Yalow while pursuing a graduate degree at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where they were some of the few Jewish students on campus.

While she hoped to work in research, she was forced to teach because few of those positions were offered to women. Eventually, she began studying how radioactive substances could be beneficial in diagnosing and treating illnesses. She used radioactive material as tracers to measure biological and drug substances, including insulin. Even after retiring in her 70s, she continued going to the Bronx VA Medical Center where she had begun her research.

All images via Wikimedia commons except image of Rita Levi-Montalcini by Mondadori via Getty Images