“Sometimes, I think I should divorce your father,” she said. There was silence. I asked her why not. I knew she was unhappy, which was obvious to me even as a child, and definitely by the time I was a young teen.

“Because I don’t have money to support myself.”

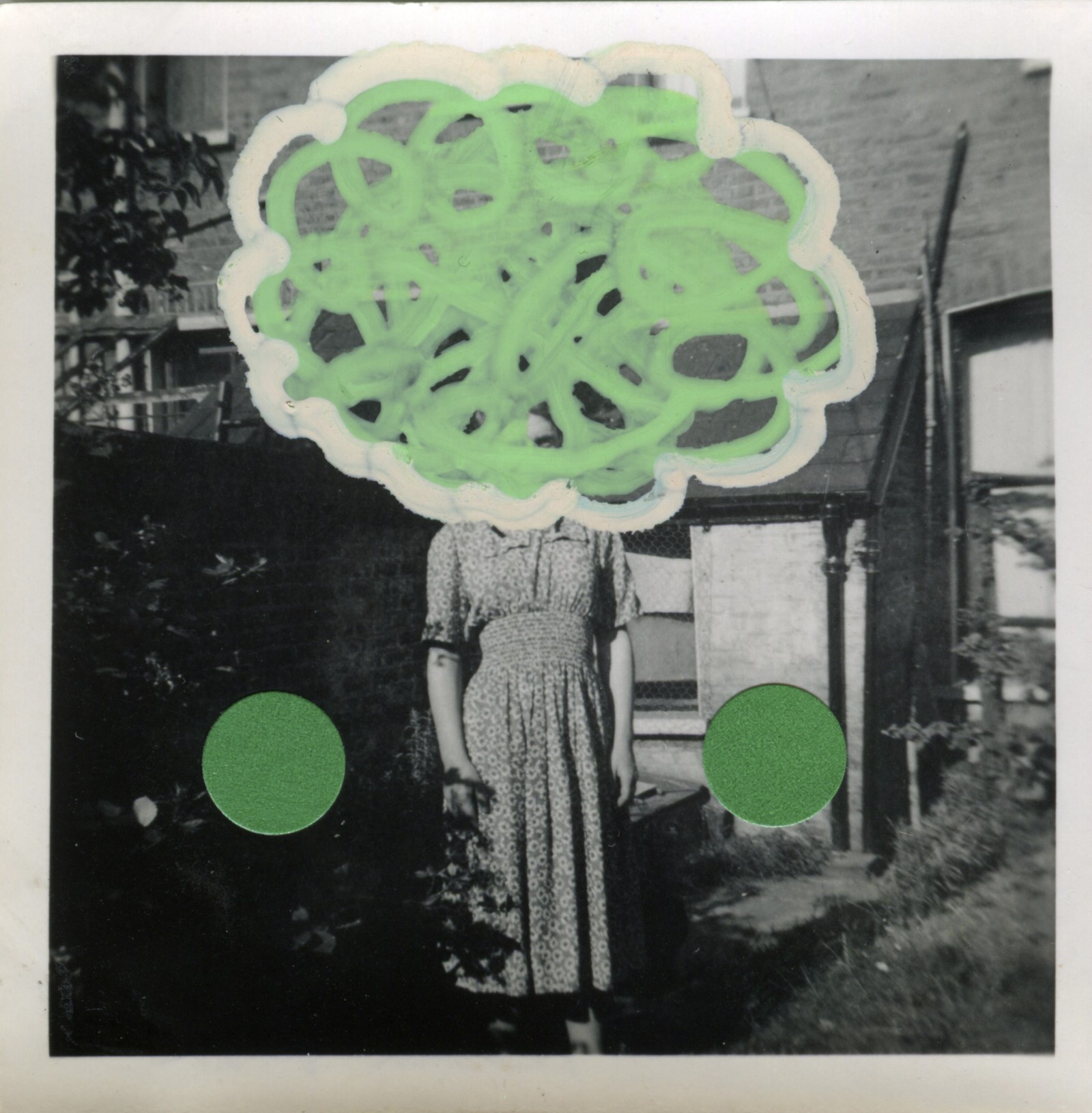

These types of conversations often happened in the car on the way home from school — or while making dinner before my dad got home from work. I was my mother’s daughter, and yet, I was also her mini-therapist. I knew too much from a young age. These memories — of my father and mother screaming at each other from across the room — all blend together in a strange cacophony of yells, almost ghostly, haunting.

There was a time, during one of their uglier fights, that my dad threatened to hit my mom. I heard it from my bedroom, having been peeled to my door, and ran out to separate them. I couldn’t have been older than 10 or 11. I could tell both of them were painfully embarrassed. I also knew never to speak of it again — even now, it’s hard to write, making it real. I know if I were to bring this up to my mother, she would deny it ever happened.

Most things like this never happened.

* * *

A week ago, my father called to tell me my mother didn’t want to speak to me anymore. It was prompted by a comment I left on a friend’s Facebook post about their own mother, sympathizing with the complicated and difficult relationship they have. Part of me was devastated, angry, and full of resentment — and the other part of me was relieved. Memories hit me like a brick wall, not simmering or pushing back, a wave full of tangles and knives.I said, OK, fine — and didn’t put up the fight that he expected me to. Perhaps I’m just too tired to keep fighting.

My mother and I have always had that quintessential tumultuous and complicated mother-daughter relationship: she always yearning to be my best friend and confidant — and me, in her eyes, spurning those efforts.

I understand why she is angry and hurt. I wasn’t always an easy child — having rebelled in every way I could (hello, art school and short hair and tattoos and punk ideals). I can’t imagine it was easy finding out, through an essay I wrote and published, that I was sexually assaulted, that I subsequently became pregnant, that I had an abortion, that I am queer, that I am non-binary. I’m sure she felt rejected, too.

But I wrote about these things and never told her because I was afraid of her judgment, of the blame, of my own accountability.

When she discovered I was assaulted, for instance, she at once reacted better than I initially guessed — but then later said I wouldn’t have been assaulted if I “didn’t invite that boy” into my room (I was in college at the time). When I subsequently went to the emergency room with a severe UTI (having never had one before, I didn’t know what was happening, but knew it was bad), I called my sister to come, who brought along my mother. While on a bed waiting for the doctor to see me, my mother casually mused that I had AIDS. I cried.

For months after, I laid awake at night, petrified of having AIDS, already dealing with the aftermath of being assaulted, feeling tainted and unlovable and alien in my own body. I waited for months (as is recommended) after my assault to get tested — and luckily, the results came back negative. Still, I was angry for being shamed by her, even if unintentionally, as if anyone should be stigmatized for contracting something completely out of their control.

Her reaction to my queerness and abortion were similar — playing into the years of shame and guilt I had been taught. Being queer and getting an abortion, according to my mother, were some of the worst things anyone could do or be. These comments were made before I “came out,” but definitely didn’t make me want to be honest with her either. When I finally told her (at age 27), she called being queer “gross.”

She supported my abortion only because “I had no choice,” but made sure to point out she wouldn’t be supportive of another, not if the pregnancy came from a consensual relationship. Of course, I always had a choice. I have a choice now. It’s just not her choice. I could have kept the baby, but I didn’t.

Through all of this, I could never distinguish whether this was guilt and shame she had projected onto me, or if what I did, or who I am, was truly shameful or strange or otherized. Something you shouldn’t talk about. So, I usually just opted to pass, because passing is easier. No one asks you awkward questions or talks about you behind your back. Maybe, I would think, she is right. There is something wrong with me.

Or maybe, I would later think, we just cannot see each other. She sees this person who has rebelled against her, against her very worldview, and I see someone who cannot understand me. I feel invisible, unseen. But so does she. I can’t imagine the pain a mother goes through to find out their child is not who they understood they were, to not understand their identity and their choices.

In many ways, I have mourned a certain loss of my mother for a long time. She is still here, and I love her, and up until this year, I have spent every holiday and Mother’s Day with her — picking out presents and writing cards I thought she would enjoy — not because I had to, but because I wanted to. Despite our differences, I knew they were differences — and always hoped that perhaps we could still have that Hollywood mother-daughter epic relationship where you spend hours on the phone or go on cute movie dates.

And yet, I never felt comfortable — something I long blamed myself for. It has been difficult for me not to feel responsible for our problematic relationship — if I was less sensitive or knew how not to let things bother me so much, to just let her ideas and comments roll off me, maybe things would be different, better. But I realized I cannot do that, however much I want to. I can only be myself.

* * *

In that moment when I heard my father’s voice — and then later, when I read a Facebook post my mother wrote about how she doesn’t even know who I am anymore, I couldn’t help but feel displaced — even if I have long been displaced from that dream mother-daughter relationship, without the support I always wanted from her. Maybe, I didn’t let her give it to me.

I hope my absence, my lack of phone calls and text messages, give us the space we need to reflect, to evaluate, to understand each other better. While I don’t necessarily want, or believe, our not talking will be forever, I want it to do good, to inspire us to start seeing each other in a better, lovelier, and more accurate light. No human is perfect. No mother or daughter can be perfect, but I hope we can be better for each other, one day.

Today I find myself writing her address on a yellow envelope in black ink, sealing the package closed, a gold necklace enclosed. During my lunch break, I’ll walk to the post office and mail it to her in time for Mother’s Day, a glittery silent reminder that I’m still here — still with love, even if that love is hard.

But for now, the silence is all there is. Perhaps the silence can turn golden. And then, into something else.