The first time I read a play by David Adjmi was in my senior year of college, though I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t heard his name before. There were several occasions when I’d tell a fellow community member that I was pursuing a degree in playwriting and they’d respond with a warning like, “Don’t write something iybe (profane), like that Adjmi kid.” It was clear that within the Syrian Jewish community of South Brooklyn, David was something of an enfant terrible.

Or at least I guessed so. I was too intimidated by the reverence of his work in the playwriting world and still caught up in my puerile battle with an “I’m unique and special” complex to ever actually read any of his plays, which I knew would hit too close to home.

To be fair, I was becoming a bit of an artistic agitator myself. In my junior year, my first full-length play was produced at NYU. It was a modern adaptation of the parable of Jacob and Esau called Left of Aleppo, where the Jacob-character, a queer Syrian Jew inspired by myself, was encouraged by his mother to keep his queerness a secret so that he can inherit the family’s home in Midwood, Brooklyn.

When the play’s event link went public online, someone bugged the system and reserved all the tickets under the names of Donald Trump and a prominent Syrian Jewish rabbi who was outspokenly homophobic. To say the experience was disgruntling was an understatement. Though the link was restored and all of the play’s performances were filled to the brim, from then on my willingness to write honest and compassionate works about the world I came from was totally shot. That was until I finally mustered up the courage to read Adjmi’s Stunning.

Set in the “SY” community, AKA the Syrian Jewish community, Stunning is about a teenage newlywed, Lily Schwecky, who during her husband’s business trips abroad develops a love affair with her Black female housekeeper. Highly stylized and scribed completely in the Syrian Jewish vernacular — “a combination of pig-Latin, Arabic, and Brooklynese” — the play exploded all conventions of theatrical legibility and told a mesmerizing tale of the struggle for self-realization in the face of deeply ingrained misogyny, anti-Blackness, and unwavering traditionalism.

To me, reading Stunning was like being given a flashlight in a dark forest of self-doubt. David quickly became a role model, who had blazed the trail for queer Arab Jews like myself, the likes of whom cannot be found in Angels in America or on Transparent.

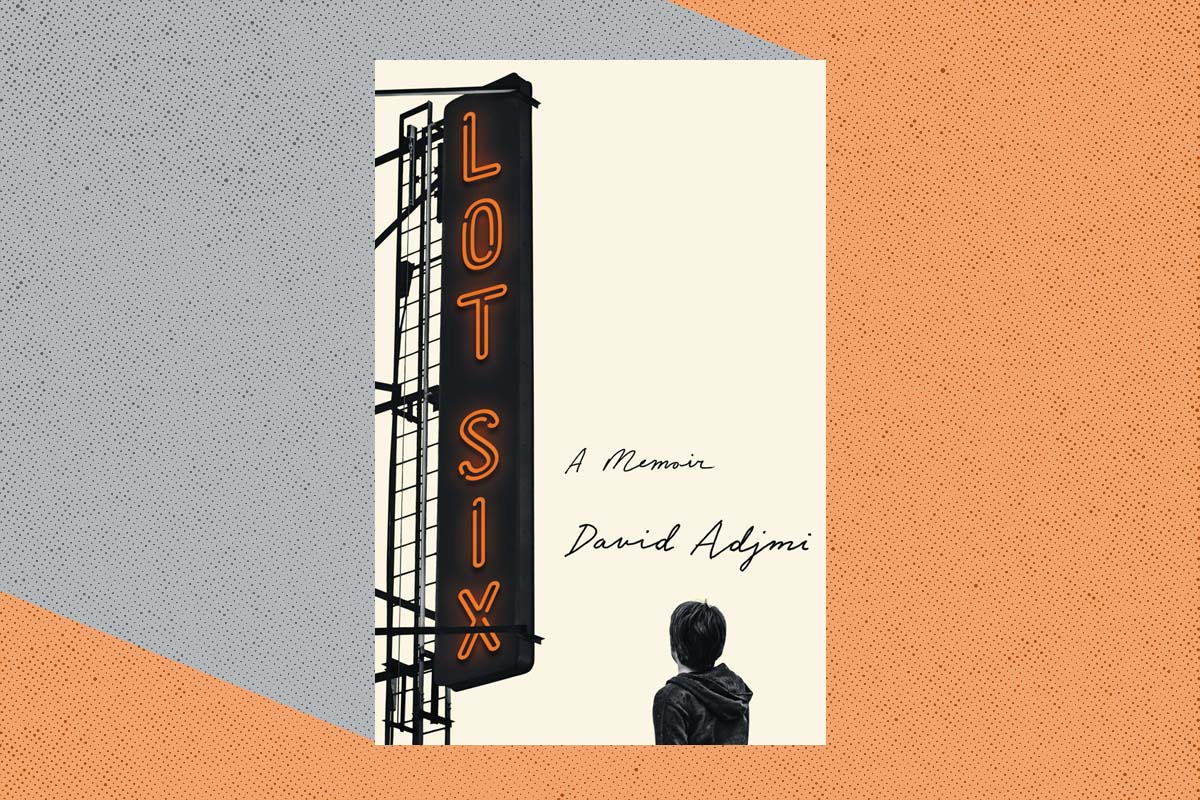

In June, Harper Collins published Adjmi’s debut memoir, Lot Six, charting his journey from being a 9-year-old yeshiva-bachur in Midwood to debuting his delightfully sacrilegious work, Stunning, at Lincoln Center in 2009. We caught up over email to discuss his new book and the shifting contours of queer identity in our community and beyond.

You’re pretty well-known in the theater world for your highly stylized worlds and idiosyncratic characters. And much of Lot Six, as we see, foregrounds the personal experiences that have seeped into your characters on stage. I wonder what the experience of crafting a character out of yourself was like?

I kind of hated it and did everything to avoid it — not because I was afraid of exposing myself, but because I didn’t know that I was skilled enough to write myself as a character. You have to be both subject and object to do it, and I just hadn’t done anything like that before. And I am not really that interested in myself. My editor and my early readers kept saying they wanted more of me. I was like, “Really?” I thought any mention of myself was navel gazing — but a good memoir doesn’t feel that way.

People want to trace their own lives and experiences against the specific contours of a main character. That’s what we do when we read books. When I started to see that as a narrative requirement, and I began to look at the whole thing as an aesthetic and narrative construction instead of a lame one-sided telephone conversation, it got somewhat easier.

It seems that it take serious artistic deftness and mastery in perspective shifting to write about yourself without being indulgent, to say the least. Even yet, you do have a way of “exposing” yourself in the book that is so rich in humility and humor, it almost counteracts the fear you describe in the earlier chapters of excommunication from the community. Do you have apprehensions about how the Syrian Jewish community might respond to the book?

I mean, I really don’t like being hated — and when Stunning came out, some of the vitriol from the community was intense. And I get it. The play was very acerbic and sort of a bitter pill. But I think the book is a pretty fair portrait. Stunning came from a wounded place, I was very pained and sad when I wrote that play. I don’t feel that so much anymore. And I have heard from a few queer Syrian Jews who wrote very moving letters to me about how much they needed a book like this growing up. There are artists and writers from the community who’ve reached out to me. So far, the response has been great.

There’s also something to say about the incongruousness of our identity markers (Arab-American, queer, and Jewish) and the way they seem to escape narrativity or perhaps only exist in the crevices between more familiar or legible narrative archives. The book certainly fills that gap for so many of us within the Syrian Jewish community, and even within the larger queer Jewish and Arab communities more generally. Given that you didn’t have Lot Six as a reference, I wonder how questions about legibility might have inflected your writing, both with this memoir and in your body of work as a playwright?

That’s such a good question. I was at Sundance last year, and one of the directors at the program asked me how I identified, and the question felt like a double bind. It made me anxious. Because I don’t know how I identify, and I have never known how to identify — and is it even relevant? Like, how do you identify me? People right now are obsessed with labels and micro-labels, as if the more interstitial and granular you get about your labels the freer you might be, but for me that sort of thinking is a little reductive.

The title of the book, Lot Six, refers as you know to SY slang for queer — but writing the book, I’ve come to see the term as shorthand for a kind of cultural queerness, or at least the part of me that’s unassimilable and can’t be conveniently slotted in a typical social matrix. But in terms of my writing, these questions are all very charged and complicated. Stunning was the only play I wrote with SYs at the center, but am I expected to be an exponent for the Syrian Jewish community in all my plays? If I don’t even feel a strong tribal identification with my own community, why would I do that? And If I’m not doing that, what do I write about? It’s perplexing and a strange position to be in.

I think what you craft so brilliantly in the memoir is that very pulsating sense of urgency and hunger for art and culture, as if becoming an artist will remedy this existential sense of worthlessness and alterity that was endowed to you by the community that spawned you. Can you tell me more about the source of those feelings and the cultural influences you latched onto during this Promethean journey of composing yourself as an artist?

Growing up, I didn’t see or feel myself reflected in my community or in my own family, and I felt very uneasy. There were things about the community I liked, there were people I loved, but there was always something a little alien about it to me. And films and books and theater and art, and even television, were ways for me to begin to curate my own inner world. Because there were parts of me — parts that were super nascent and unformed — that were mirrored back to me in these cultural artifacts. So they gave me a way to understand my place in the world, and a sense of the scope of possibilities for me outside my family, and the community — which had a very right wing patriarchal vibe.

I matched my own life circumstances to the narratives in film or plays or television shows, and I’d make new inferences about the kind of life I might have, the kind of person I might become. Art is a technology that allows us to process and experience aspects of life by proxy, which is why it is invaluable. And I was very culturally omnivorous, I didn’t know what culture was exactly — I just wanted to be bombarded with stimuli.

From Marie Antoinette to 3C, you do an incredibly good job at centering the grievances of queer folk, women, people of color, etc. Could you speak more about this act of re-imagining stories through the fulcrum of your experience?

I was very lonely as a kid, and at the center of that loneliness was a feeling that the world was a happy place, with well-adjusted people who enjoyed themselves. I was not well-adjusted, nor did I really enjoy life. So I was depressed because of the circumstances of my upbringing, and the depression was compounded because of this other sort of meta-isolation. I was isolated even in my isolation. I couldn’t match my own feelings of alterity and sadness with these glittering surfaces, with all the wealth and pleasure surrounding me.

Of course, I came of age in the 1980s, so these rifts felt very, very extreme. I guess I became obsessed with the rifts and wanted to dramatize them once I started writing plays. I also think my closetedness is multifaceted, and has been very hard to articulate or climb out of, and my early plays in particular are almost these reenactments of the experience of living in this closet. They are in some ways PTSD plays. They are hysterical and off kilter — tonally and otherwise. And they are plays about existential isolation, because… well, write what you know.

Speaking of existential isolation, in a recent interview with McNally Jackson you said that “the people who need to read this are people like me… I want people who are younger, people in their 20s to read it. People who need to feel hope.” Do you have anything more to leave us young aspiring artists as we face the tumults of the day?

Stay in the light. Stay off social media. Read books, because they humanize you. Find something you love, because where there is love, there is hope.

Header image design by Emily Burack.