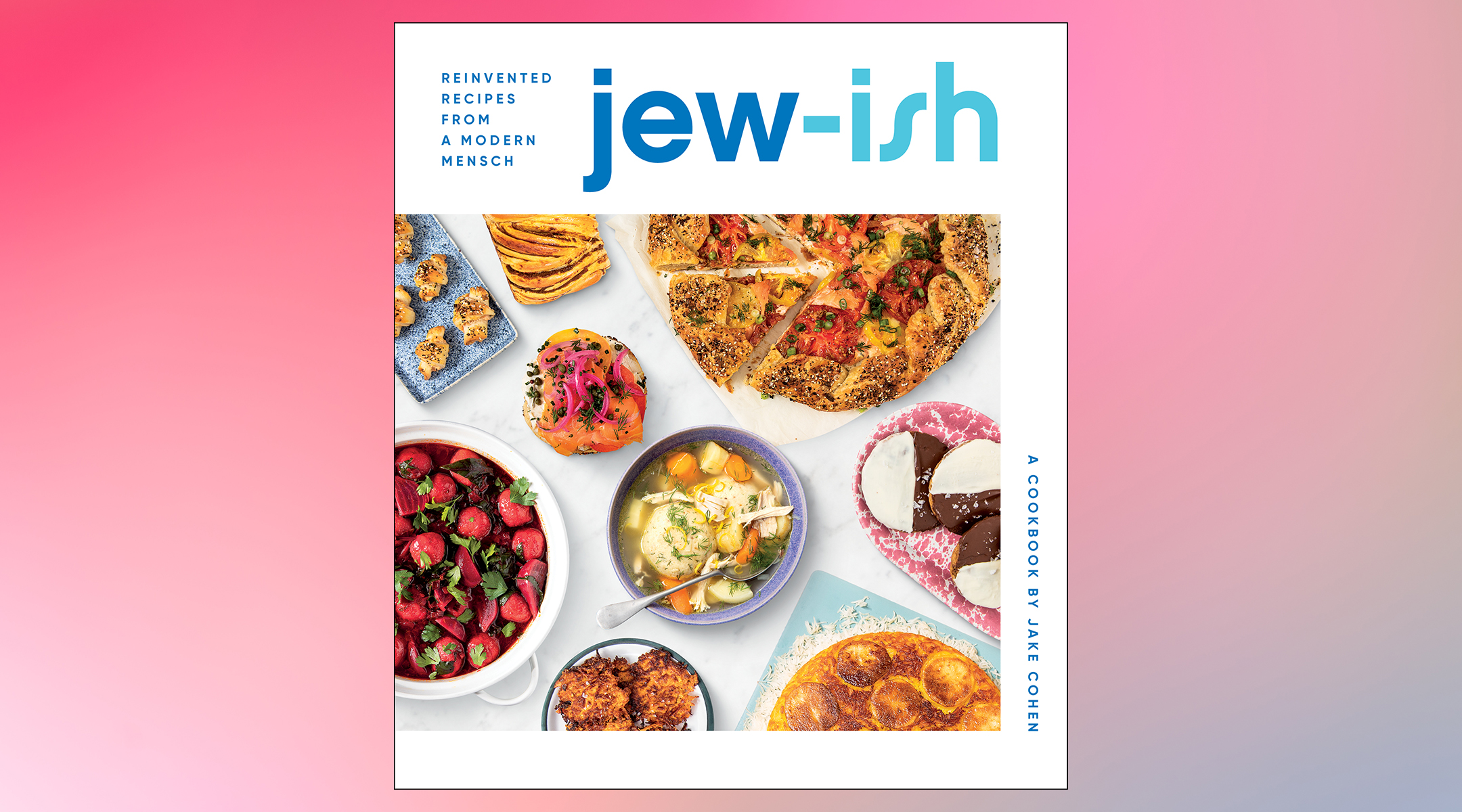

Jake Cohen’s debut cookbook, Jew-Ish, is a delight. Subtitled “reinvented recipes from a modern mensch,” the book is dedicated to the increasing popular food writer’s husband, Alex, because “this book is nothing short of our love story,” detailing their shared Jewish journey and different Jewish upbringings. Jake is Ashkenazi and Alex is Mizrahi, and along with the delicious recipes — seriously, rose water and cardamom challah French toast, anyone? — the book explores how they’ve figured out what it means to be Jewish in 2021. Jew-Ish takes the reader through a bevy of foods around Shabbat dinner, with bonus chapters for Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur break fast, Hanukkah, and Passover.

Cohen, 27, studied at the Culinary Institute of America and began his career working at New York City restaurants before transitioning to food media, working at Saveur magazine, Tasting Table, and The FeedFeed. Last year, he transitioned to full-time freelance and content creating — something he can do because of his large and engaged following on Instagram and TikTok, where he has amassed nearly 900,000 combined followers across both platforms. Following him on social media makes you feel like you know him — Cohen is warm and inviting, and breaks down his recipes in accessible and fun ways.

And what you see on social media is exactly who Jake Cohen is: There’s no phoniness, no putting up a picture-perfect mask for his followers (though his food photos — especially his cheese boards — are quite literally picture perfect). Speaking to him proved to me that the Jake Cohen of TikTok is exactly the Jake Cohen of New York City, the one who lives with his husband, Alex Shapiro, and loves baking challah.

In a long conversation that spanned favorite Shabbat dinners, Jewish grandmothers who don’t cook, and how challah changed his pandemic experience, I chatted with Jake about all things, well, Jew-ish.

What does it mean to you to be Jew-ish? As someone who identifies as a High Holiday Jew, I feel this.

The idea of being Jew-ish has become so problematic in the sense of distancing yourself. When I grew up, and people referred to themselves as “Jew-ish,” to me, it seemed as if they were stepping away from their Judaism and their identity. So this book is called Jew-ish, but to me, that is referring to the food and the way I celebrate Jewish ritual and Jewish customs. But myself, personally, I’m Jewish, full stop. No hyphen.

That is part of the journey that I’ve gone through with my husband: This idea [that] we grew up in households that really didn’t foster a deep understanding or connection to our identity. In my case, [there was] the added demand of Hebrew school and a bar mitzvah, and then you could quit everything. In my husband’s case, he didn’t even really have that opportunity to go to Hebrew school or have a bar mitzvah. As adults, we are in this place where we get to make our own rules, we really get to explore what we would like, and take the good, leave the bad, and make it our own.

That is the core of what I try to explain in this book: If you have any connection to Judaism, whether that be your own personal lineage, a significant other, a roommate, a friend, an interest, then what better way to explore that through food and Shabbat! And while you’re going through that, make it your own. Break the rules, make your own rules. I’m not a rabbi, I don’t pretend to be a rabbi.

For me, I grew up around so many Jews, and I was like, well, I’m not religious or anything, so I’m not really Jewish. And then I got to college, and I was like, Oh, no, I am Jewish.

Totally, 100%.

I loved how you write about recipes you developed along your journey of hosting Shabbat meals. What does Shabbat mean to you?

When I got introduced to OneTable, it was beshert. It was this really important time in which we were not only trying to figure out what our Jewish narrative would be as a young couple, but also how we were going to make friends. We didn’t have many friends. Where do you meet people? Where do you find people? We wanted to make gay friends. We don’t drink, so it’s not like we’re gonna go to a gay bar and hang out with people and make friends and have a community surrounding a ritual of drinking that we actually hate. To us, it was like, well, what can we do?

The first thing was like, great, let’s try synagogue. We went CBST [Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, an LGBTQ synagogue in New York City], we tried some services, we do High Holidays at Central [Synagogue] every year. We’re like, this is promising! It was wonderful, I enjoy it, [but] it’s not something that we could put [energy] into, to the degree that we would be getting out of it what we were looking for. When I found OneTable, that concept of Shabbat was really it. Because it kind of combined everything we were talking about — in the sense that it brought people together, it was all around food, everything we loved, boom.

My first Shabbat was a dream. It was 12 people. They’re all hosted at my mother’s apartment — we live in the same building. It was a queer-focused Shabbat. It was my husband, myself, a friend from high school, Adam Eli, this guy I knew from Instagram, Evan Ross Katz, who is a fashion writer who has now become one of our best friends. All of these different people from queer Jewish community. It touched each person in a different way, because it was an aspect of extending hospitality that also related to this idea of nostalgia, of something they used to experience.

There’s something very unassuming when you reach out to someone even if you don’t know them, and say, “Hey, you want to come for Shabbat?” Shabbat is just so cozy and warm.

So how did your journey into Shabbat correspond to your process around writing Jew-ish?

That journey and writing this book really all happened at the same time in the sense that, shortly after is when I started to really realize that this was it. This was the way I want to talk about Jewish food. This is the way I wanted to talk about my Jewish identity. This was this moment of the week in which I got to cook for others, which I love to do, but also explore the dishes that I grew up with — the Ashkenazi foods that I never actually cooked myself. When you live in New York, it’s like, when do you ever make your own matzah ball soup!? Likewise, I got to explore a lot of dishes that my husband grew up with that were completely foreign to me and often also completely foreign to the guests who came. I tried to make sure that at every meal, there were people that I never met before. And that was either cold-reaching out to someone I had known from Instagram, or I would save a few seats and tell guests to bring friends.

We’re at the one-year anniversary of the pandemic, and obviously you can’t host Shabbat dinners, you can’t gather in the same ways we have been able to gather in the past. How has your practice of Shabbat shifted?

My Shabbat practice has shifted, but also the way that I create community has shifted. For Shabbat, it used to be these tables — my husband would look up on YouTube these fancy napkin foldings, and I would cook this meal and it was all silverware and crystal. And now it’s my sister, her fiancé, my husband, myself, sometimes our mother, in our onesies. There’s challah. Sometimes we just get take out. Sometimes there’s a bong at the table. It’s whatever we want to make of it. And there’s something beautiful about that, too, that I love. And I will probably keep, even post-pandemic.

Likewise, the idea of community building through sharing recipes and through celebrating Jewish culture on social media has exploded in the past year. The [pictures for the] book were shot the week before lockdown; our last day of shooting was the day that New York went “on pause,” that night. So we really got it in at the eleventh hour. So the pandemic was really focusing on first, finishing the book, and then going through edits and that whole process — while managing the craziness of the emotional strain.

It was a big growth experience. It was a time in which I put a lot of energy towards challah. I bake challah every week now on Shabbat, which was something I never did before, it was a special occasion thing. Every Friday I bake challah. Every Friday, since the beginning of the pandemic, since that first Shabbat, to now. That’s been a huge, huge, huge blessing.

Is that something you hope to continue post-pandemic?

Oh 100%. It’s so therapeutic and there’s just nothing like it. It’s funny, the photo in my book of challah is not actually the recipe in the book. I had this fancier recipe with caramelized honey. It was more of a finicky dough. The challah is so delicious, and it’s decorated with all of these seeds like Breads [Bakery] does. Super extra, super ornate. But when we went into lockdown, I realized that just wasn’t functional on my weekly routine. I simplified the recipe. I made it perfect. I made it my own. I brought it down to its core, like, what is the equation for a perfect challah? And that’s the recipe in the book. And again, it’s a photo of challah, so at the end of the day, no one’s gonna fucking know.

Until this interview!

Until this interview, and I’m very open about that, because I never have anything to hide. But I want everything in the book, including the challah, to be something that you can do really easily — not easily, obviously, we know everything’s a learning curve — but that everyone can be empowered to do anything on a weekly basis and not have it add stress. It should add joy, not stress.

In the same way, that concept of adding joy not stress is what I’ve done. I left my job at the FeedFeed, I am now very blessed to be able to sustain myself on my own. And a lot of that has been through sharing recipes on social media and the power of TikTok — sharing Jewish ritual and Jewish culture on TikTok.

Yeah, I actually want to ask you about that. You’ve obviously garnered such a huge following on both Instagram and Tiktok. What has been the most surprising part of creating that community on these platforms?

I’ve always been obsessed with pop culture. I’ll never forget my memories of my sister and I going to Hebrew school on Sunday, we’d rush home to the TV because on VH1, they would play that night’s episode of Flavor of Love early during the day. I’ve always had such an obsession around reality television, anything that would enter the zeitgeist.

You get what you put into anything. When it comes to social media, there’s a lot of negative things around it, but you get to choose what you want to get out of it. And to me, I decided that I wanted it to become this place in which people could experience me, my food, my perspective — authentically, and 100% without any censorship. That’s why on Friday night, I’m doing AMAs where you can see I am visibly stoned out of my mind and talking about ridiculous opinions on certain things.

I leaned into Judaism because that was what my husband and I were exploring in terms of our identities, and I started to really resonate with Jewish culture, Jewish tradition, in a very modern way. When I started to see other people respond similarly, and feel like they had permission to explore those aspects of their identities with that same kind of freedom, that brought me more joy than anything else I’ve ever done professionally. And that’s all I want to do. And now, as soon as I’ve done that, my new crusade is fighting Ashkenormativity. And this idea of what is Jewish food? What is Judaism? What does it mean to look like a Jew? What does it mean to cook like a Jew?

The idea of what a Jew looks like, and what is Jewish food, are things that we think about at Alma every day.

Of course. I will say, even with what we have done, we have to constantly check how our upbringings have coded us to think a specific way. It’s a constant journey, even for Jews. To me, what kickstarted that, especially in terms of my work being around food, has been the fact that this book is this love story between myself and my husband. He’d never had babka when we met, and I never had kubbeh!

@jakecohen Her burghul b’seniyeh is like a cliff notes version for the real thing!! #Levitating #levant

♬ Say So (Instrumental Version) [Originally Performed by Doja Cat] – Elliot Van Coup

We got to really explore what Jewish food meant to both of us in this vacuum. That was so beautiful. And that’s why I think one of the hardest parts, when people see recipes of mine, and they criticize, like, “Oh, well, that ingredient is hard to find.” To me, it’s like, it’s hard to find for who? Because what you’re saying is that you don’t want to put in the work to accurately represent someone else’s culture, because it doesn’t fit your idea. It doesn’t fit your fantasy. But at the end of the day, if we’re making ghormeh sabzi, a Persian stew of herbs and kidney beans, you need dry Persian limes. You can get them on Amazon, you can get that anywhere. You can’t expect everyone to bend over for your comfort.

In your acknowledgements, you thank your grandma Annie for showing you the power of cooking at a young age, and Alex’s mom, Robina, for teaching you so many of the recipes of her culture. Can you talk about the impact your family and your husband’s family has had on your cooking?

I grew up in a family that had a lot of great eating. I grew up in Bayside [Queens], my grandmother Annie lived in Forest Hills, my sister and I would go spend weekends with her. She would cook these feasts: lamb chops and spaghetti and asparagus with melted gouda. She would have such an array of food for two people. To me, it was that first concept of extravagance and abundance. It’s the same thing as having two challahs on a Shabbat table — that idea of abundance around food with people you love is so special. I found that equally with my other grandmother, Marilyn, who passed last year. She was one of our best friends. Alex and I were very close with her. When we moved to the city, she lived in the Village; she was who exposed me to the New York food scene. She was the person who opened pandora’s box in terms of, “No, no, this is great food. This is what your norm can be in New York City.” And it did! She didn’t cook at all.

Unfortunately, it didn’t happen until much later on, until I was doing this book process, that I really started to explore what [my grandmothers’] histories were in terms of Judaism. Annie was a hidden child during the Holocaust; my family was from what’s now modern-day Lithuania. They were living in Belgium, her parents were both in the camps, and they both survived. But then her mother ended up leaving her father and taking their three kids to New York, and my grandmother grew up in a religious household and was kosher until she met my grandfather who had a similar situation — they were Germans living in Belgium, and they fled to New York, but were turned away and went to Cuba where my aunt was born and raised, and then made their way to New York.

She would say stories, like, “Oh, my mother used to make gefilte fish, she would have the carp in the bathtub and cholent.” And I was like, “Why didn’t you ever make that for mom, or for us?” Because my mother never heard of cholent when I made it for the first time. And it came down to as simple as, “Your grandfather wasn’t kosher.” So [they] had the Jewish foods for the holidays, but something like cholent is so rooted in people who keep Shabbat.

With Marilyn, she was the first generation in New York; her mother came over from what was Russia, now Poland, and came early on after the First World War. She had a completely different experience. She was a single mother who raised my father and didn’t go to college until he went to college — and then went on to get her masters. She’s had so many different careers and is such a huge inspiration. She wasn’t religious at all. Wasn’t what you would expect a Jewish grandmother to be.

You have to remember that so much of that is so colored by their trauma. We talk about this all the time; we have issues with the way that my grandmother reacts to things or people, as then as a result, the way that my mother and her brother react because of the way they were raised. I always tell my sister, we have zero comprehension of what it is like to try to go on with your life after the lives they had to go through.

Also seeing that through my husband’s family, of his mother having to go through the revolution in Iran, and their family having to leave everything and come to the States. The story she told of packing a suitcase, locking their apartment, and just leaving. This is my mother-in-law! This is not far away. You just have to remember that. You just have so much more empathy for others, and their lived experience, especially when it surrounds persecution for being Jewish. That’s why it makes it that much more important to me to celebrate and preserve.

I’m obsessed with all the headlines, like the “just like a prayer, I’ll take you there” introducing the Shabbat prayers and the “koo-koo” for kugel and “rugelach’ed out of heaven.” How did you come up with these?

Puns have become so integral to my social media presence! But it also goes to the fact that I don’t take myself very seriously, I don’t take my work very seriously. I don’t think people should take food or the way they cook very seriously. They can get a lot out of it — there can be a lot of deepness and meaning to it — but I don’t think that it should be precious. To me, that was just ways to add some punch lines and remind people it’s Shabbat! I’m not asking you to make a brisket and daven [pray]. I’m asking you to have dinner with your friends and family, and take a moment to yourself. That comes across better when you add a little levity to the situation.

Okay, to end, some quick questions. Did you have a bar mitzvah? What was the theme?

I did. I had a b’nei mitzvah with my sister. It’s so embarrassing, it goes against everything Alex and I fight for. It was so just riddled with privilege. It was on a yacht that went around the Long Island Sound, so it was nautical themed and every table was a different nautical movie. My table was The Life Aquatic.

Who is your favorite Jewish celebrity?

Ina Garten. And Barbra Streisand.

What is your go-to bagel order?

Okay, so two. It depends on the mood. I’m very much a big fan of anything in the bacon, egg, and cheese family. And I’m not picky. It could be bacon, egg, and cheese, it could be ham, egg, and cheese, it could be pastrami, egg, and cheese. It’s all non-kosher. All delicious. On the other side, I love tuna on cinnamon raisin. I scream about it from the rooftops.

With lox, I’m very traditional. I need lots of onion, lots of tomato, a little bit of cream cheese. I hate bagel shops that put a fucking inch of cream cheese. No one needs that amount of dairy, especially the Jews!

Least favorite Jewish food?

So much of it is rooted in foods that are no longer necessary. So probably the best example would be ptcha. Are you familiar with ptcha?

I only know that because of my job in Jewish media.

There’s no need for meat jellies in 2021! So, I’m gonna say that.

And last but not least: Your favorite Jewish food?

It’s a tie between challah and matzah ball soup. I have matzah ball soup all the time, it is true Jewish penicillin. And challah, throughout this whole process of quarantine and the book and perfecting it, is so magical. And it’s so Jewish. Nothing pisses me off more than people trying to pass a challah and call it “braided brioche”! That is antisemitism in 2021. To me, challah is so powerful and beautiful.

All images courtesy Jake Cohen.