Rachel Bortnick is a Ladino teacher based in Dallas, Texas. She was born and grew up in the Turkish city of Izmir, also known by its former Greek appellation, Smyrna. Now in her 80s, she’s looking back on a life impassioned by her language revitalization efforts of the endangered Judeo-Spanish dialect, which has been preserved by Sephardic Jews in Turkey since the 15th century.

Ladino is known among academics for maintaining the sound, vocabulary and culture of Miguel de Cervantes, who was born in early modern Spain shortly after the Inquisition expelled the nation’s Jewish population. It is said that the chief rabbi to Beyazid II, the second sultan to sit on the throne in Constantinople, invited the Spanish Jews to settle in the Ottoman Empire, mostly in Thessaloniki (also called Salonica), Istanbul and Izmir. They soon mixed Greek, Turkish and Slavic elements into their premodern, transnational tongue.

In conversation, Bortnick, who also speaks Turkish, remembers growing up in Izmir in the years immediately following World War II, before tens of thousands of Jews in Turkey resettled in Israel. Then, the Aegean port city still boasted a large, proud Jewish community who primarily spoke Ladino. She remembers seeing her grandfather write in Ladino, which sparked her curiosity to eventually read and teach the language. She brought together students and colleagues through the online group she founded in December 1999, Ladinokomunita, which remains active as the first and largest virtual educational network exclusively in Ladino.

From her home in Dallas, where she lives with her American husband, she reminisced about life as a Jewish girl growing up on the west coast of Turkey, where her family sometimes read Şalom, Turkey’s Jewish newspaper, which was printed in Ladino. In fact, Bortnick is an amateur scholar of Ladino literature, and we also discussed her journey toward literacy in the language of her forebears — which is sadly dying out but, thanks to her work, has life in it yet.

This conversation has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

I’m interested in learning more about you, and about how you approach Ladino as a reader, teacher and speaker.

I was born and raised in Izmir, Turkey. I’m 82 years old. I am, among other things, the founder of Ladinokomunita. I started it in 1999 as a forum. It’s a correspondence list. It’s still going strong. At its height we had about 1,700 members, now close to 1,500. It’s a Ladino-only group, and was the first ever such group on the internet. You can’t write about Ladino today without mentioning that.

Many of the original active writers whose home language was Ladino have passed. Interestingly, now we have new people signing on who are not necessarily of that background at all, or are and did not know the language and want to know it now. We get new young members now.

What was your upbringing like as a Ladino speaker in Turkey?

I grew up in Izmir in a totally Jewish environment where most people did not know any other language besides Ladino. I married an American. Being away from the language for so long, it all started with my nostalgia. Everyone I used to speak it with started dying, one after another, starting with my father.

It’s a very long story, but the more I learned about the language, the more I fell in love with it. I think it’s one of the most interesting and sweet-sounding languages that there is, to me, anyway. It’s so interesting for several reasons, but mainly because in it is contained the entire history of the Sephardic people, from its origins, to where they’ve been, who their neighbors were, just taking it all in in different ways.

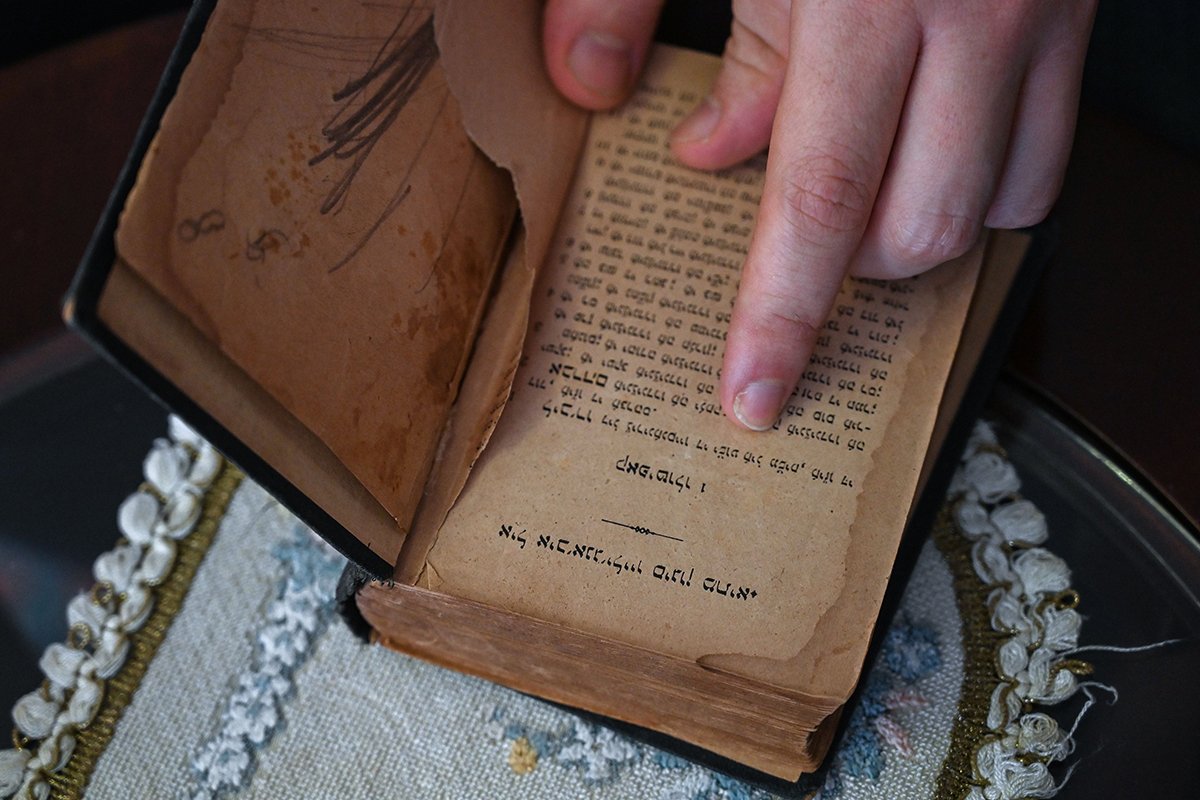

Of course, our language is the main expression of our culture. I have done some reading of old [Ladino] literature written in the Rashi (print) script, not so much the handwriting script, which is called Solitreo — I find that very difficult to read. Neither the Solitreo nor the Rashi was taught to us in Turkey. My mother’s correspondence with her sisters who were living abroad was all in the Latin, print script. I imagine that my father knew Solitreo, but I never saw him write anything in it. Everything I was exposed to was in the Latin script.

Did the transition in Ladino from Rashi and Solitreo script come about through the language reforms of Ataturk? As the first president of Turkey, he modernized Turkish by shedding its spelling in Arabic script during the Ottoman era. Other minority languages, like Ladino, also shifted from Hebrew to Latin transcription. Was there a parallel history there?

Pretty much. It actually started before that, from what I have been reading. I was never exposed to that. We called our language “Espanyol.” Some people called it “Judio,” which means Jewish, but that was simply a translation of what the Turks called it most of the time. “Yahudice,” they called it.

Some people said, “No me hablas in Judio,” meaning, “don’t talk to me in Jewish,” kind of. But mostly all of us called it “Espanyol.” We didn’t know it was any different from what other Spaniards spoke. We never met a real Spaniard. We just knew it as Spanish.

My maternal grandfather, the only one I knew, had a store that sold men’s yard goods, materials for clothing and a tailor’s shop. In other words, he made suits for men there. He kept accounts in strange handwriting that I saw. Then I saw him also write a letter to his daughter in America. I said, in translation, “Grandpa, what are these hooks that you’re writing? They look like little hooks.” He said, “that’s called Ladino.”

That’s the only time I heard that word in Turkey. When I came to America, in 1973, my mother came to visit me. We were speaking and the neighbor came and heard us and he said, “Oh, you’re speaking Ladino, I thought that was a dead language.” I said, “I guess he means our Spanish.” That was the first time I heard the word Ladino. Since then, I accepted it as the English word for our Spanish. After reading the history, I think that’s a very appropriate name for it.

Our language, besides the vocabulary, kept many sounds of medieval Spanish that have since disappeared in modern Spanish. The system that we use to spell our language is perfect, because it reflects those sounds. The best-suited spelling is the Turkish spelling. We use the international English keyboard, which makes it easy to write in the internet age. I learned Rashi here, in the U.S. — I can read the printed Rashi. I read a few things and have done transcriptions and translations. But mostly I read in the Latin script. I’m always on top of anything that’s being published in Ladino.

Now, with us being at home, Zoom has been a big boost for our language. We have all kinds of programs going on. One of them is a weekly Sunday meeting all in Ladino, called “Encontros del Ahad,” or “Sunday Encounters.” We are a few hosts. It’s like a talk show, and at the end we have people calling in with questions or comments. I interviewed a real leader in the preservation and promotion of Ladino, Moshe Shaul. He’s also an Izmir native. He is the founder and editor of a cultural review all in Ladino which unfortunately stopped publication on paper in 2016, but it has been revived online. That publication is called Aki Yerushalayim.

When you were growing up in Izmir, were you reading books in Ladino?

No. I was reading nothing except letters, letters that came from abroad. My mother, especially, was one of eight brothers and sisters. One of her sisters lived in Barcelona, the other in Cuba for a while and then in America. She corresponded with them regularly. So letters came from them. Other than that I did no reading in Ladino.

Occasionally, my father would bring the Şalom newspaper from Istanbul. In my time, Şalom had more Ladino in it. I was born in 1938. In 1984 — I remember that date because I was getting Şalom and was in touch with some of the editors and writers there — a younger group took over. The original publisher, Avram Leon, had died or couldn’t keep it up anymore, so a younger group came and decided to make it mostly in Turkish, with just one page in Ladino.

In 2004, I was in Istanbul. Şalom invited me to a meeting with the writers of their Ladino page and asked me what I thought, and told me they were thinking of starting a monthly supplement all in Ladino. I said that’s great, look at Ladinokomunita, our members keep growing. From then on, they started. In 2005 the first issue of El Amaneser came out.

What are your thoughts on early Ladino literature from the 19th and 20th centuries?

It’s obvious that people were more inclined to read letters, and also that there were more women readers. It seemed that it would have appealed to women to read these love stories, more than to men. It shows that literacy among women would have risen a lot then. The fact that they were short also was a way to get people to read. They were serialized to make them want to read the next episode and so on.

I think what’s being written now is more interesting to me. What is being written now is more relevant to my own experience. It’s also more pleasurable for me to know that the language is being kept alive. And the subject matter is more relevant. I also think it’s amazing that, as I told you, there are classics that have been translated into Ladino by Moshe Ha-Elion in Israel, like his Ladino translation of Homer’s “Odyssey.” I have those books. I appreciate them as works of literature in Ladino; however, I enjoy reading stuff that is about my own times.

I’ve been so lonesome. Except for six years in the San Francisco Bay Area, I’ve never lived in a place where there was even a little group of Ladino speakers. I lived in St. Louis, Missouri. I now live in Dallas, Texas; there’s one or two other people who speak it a little bit. I’m very nostalgic for my language, and for people who shared more or less the same time frame in Ladino, as I did. I enjoy reading new things that are coming out, in that sense. And also, Holocaust remembrances, I do like reading those. And poetry, I think it’s amazing when people write poetry in Ladino.

Who would you recommend for contemporary readers curious about Ladino literature today?

The poet Margalit Matitiahu, or someone like Haim Vitali Sadacca is an old-time rhythm and rhyme expert. His thoughts are very humanistic and sensitive, but he pays great attention to rhythm, rhyme, stanzas and styles from his era. He died only a couple of years ago at the age of 96. He was, to me, like living history. Then there are the modern poets who are wonderful also, with more free verse.

I have a whole library here. I never ever experienced anything like this when I lived in Turkey. Even though everyone around me spoke Ladino — most people spoke nothing else — I had no books in Ladino like I do today living in the U.S. But, in Turkey, my world was all in Ladino, or Spanish, as we called it, my home and neighborhood.