Over the years of working at Hey Alma, I’ve found that the Jewish art we feature on our site and Instagram page often begets more Jewish art. After winning our fourth annual Hanukkah movie pitch contest, writer Beth Kander turned her movie plot into a book. Jewish Polynesian artist Anneliese Rosa was inspired to make her clay golems genderless after reading a Hey Alma article about golems being a queer icon. Simone Nathan, the creator of the extremely Jewish show “Kid Sister,” asked her production team to use Hey Alma’s Instagram as a reference point for young Jewishness.

And on Sept. 17, 2024, HarperTeens will release Hey Alma contributor A.R. Vishny‘s debut novel “Night Owls.” This contemporary romantic fantasy tells the story of estrie sisters Clara and Molly — ICYMI estries are bread-eating, owl-shifting Jewish women vampires — who live in a former Yiddish stage turned movie theater in the East Village. Despite agreeing to never fall in love, Molly has a secret girlfriend named Anat and she’s tired of hiding her. But when Anat disappears and Clara suspects it’s the work of Boaz, a himbo Israeli-American teen who works the theater’s box and can see the undead, the sisters must work together against the forces of New York’s monstrous underworld.

In her own words, A.R. describes the book as “basically ‘Twilight’ but by way of everything I’ve ever written for Hey Alma.”

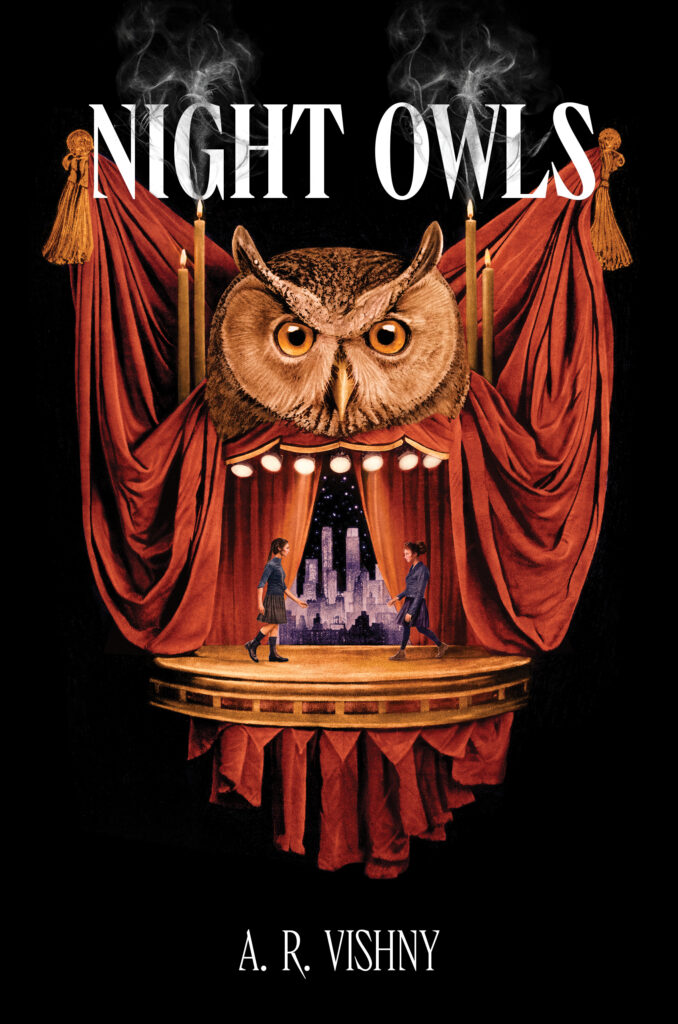

Now, in anticipation of the “Night Owls” release later this year, Hey Alma is pleased to exclusively reveal the absolutely magical cover art. Drum roll please…

Speaking on behalf of everyone at Hey Alma, we’re going to break the rules and judge a book by its cover: “Night Owls” looks incredible and we cannot wait to read it.

To learn more about what’s between the pages of this gorgeous cover, Hey Alma spoke with A.R. Vishy via email about the shout-out we get in chapter two, Jewish writers that influenced “Night Owls” and what inspired her to write a book about Jewish women vampires.

The following conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

I’m obsessed with the cover art for “Night Owls.” What was your immediate reaction when you first saw it?

I was flying out to my cousins for Rosh Hashanah when the first sketch landed in my inbox, and I literally spent the entire flight just staring lovingly at it. It blew my mind. Authors generally don’t have much say over their covers, so I was very anxious in the lead up to seeing the sketch. For this process I sent my publisher a mood board, a face cast, some general rambling thoughts and they came back with a couple of illustrator ideas.

This captures the vibe of the book so perfectly, and particular ideas I play with in text about transformation and the blurring between theater and reality. I feel incredibly lucky to be debuting with a cover this unique.

What inspired this book? Why estries? Why Israeli Jewish himbos? Why queerness?

The initial spark of inspiration was the setting. I started the first draft of this in April 2021, before COVID vaccines were available for everyone and before the things that make NYC worth the rent had actually reopened, and I missed it terribly. I lived in the East Village for years and am nerdy for the neighborhood’s history, and the fact that the same city blocks gave us Yiddish Theater and punk music. I wanted to go back to a time when I could spend a long afternoon wandering down to the Holy Land Market (z”l) on St. Mark’s for fluffy pita and a tub of Ha’shachar Ha’ole chocolate spread, getting pierogis at Veselka or B&H Dairy and then catching a movie at Village East by Angelika, which is an indie cinema on Second Avenue that was formerly a Yiddish stage, and still has a lot of its original details. That neighborhood and specifically that cinema is magical to me, so I figured I’d start there.

Once I had the setting, and because I write YA, I then asked myself what 14-year-old me would have been obsessed with, and the obvious answer was vampires.

Estries, Jewish women vampires, were perfect for this project. For me, the secret to writing a Jewish folklore story that feels authentic is to have a clear understanding of what this monster is and why Jewish culture would produce such a thing. Golems are pretty easy — they’re usually born out of a need for protection, and there’s a lot of other versions and takes to draw on. For estries, there’s much less. But they ordinarily appear as women, unless they’re shifting into something else. They can move unseen in Jewish communities, they can enter and interact with sacred spaces and they feed on men in the community (also bread and salt). They overlap a bit with Lilith, who we often think of as this hungry, vengeful figure who exists in opposition to the roles traditionally ascribed to women. The estrie became a way I could portray that duality: the Jewish women who I know and know have existed not only in my own life but throughout history whose strength, ambition and grit are so great that they could outmatch death, but who so often go unseen and unremembered. It became a way to think about ambition and sexuality in Jewish women and the extent to which both are treated as undesirable and even monstrous, both within Jewish communities and in the non-Jewish world.

Part of making the story also feel authentic and rooted in something real is to make the Jewish world feel like what I know. My mom is an American Ashkenazi Jew with a long family history in the Boston area, and my dad is Israeli. Most of my extended family is a mix of Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, a lot are very culturally Israeli whether they live in Israel or in the Diaspora and our family-friends-who-are-like-family come from all over the world. None of that felt unusual growing up, but it’s not often what contemporary American Jewish spaces look like in mainstream pop culture. I hesitate to call it “Ashkenormativity” because it’s not even an Ashkenazi experience I really recognize — the flattening produces a type of Jewish person I for the most part only ever see on TV. So when I sat down to write I wrote what I thought would feel more like what I know to be true, which is that if you take a slice of Jewish life, especially in a place like Manhattan, there’s a mix of influences, history, culture and languages and that’s all very ordinary and just part of being here. So this is a Jewish world where a hungry shtetl girl, a Yiddish stage starlet, an NYU freshman from Ra’anana and an Israeli-American day school grad from Brooklyn (who yes has a big heart and not much brain) can save the world and make out.

Pleeaaassseee tell us more about the Hey Alma shout out.

Hah, canonically you all are big fans of Anat and Molly’s “The Second Avenue Spiel,” the cool Yiddish theater history TikTok account they’ve been working on behind Clara’s back. Hey Alma was my first paid byline, and where I really honed my voice as a writer. I owe a lot to you all.

I saw you posted about revisiting Kadya Molodowsky’s froyen lider poems while revising “Night Owls.” How has Kadya influenced the book? Did any other Jewish writers influence you?

Yes, many! I often look at poetry before sitting down to revise, it’s like a concentrated hit of emotion and a reminder to think about word choice and sentence rhythm. For this book, I loved Kadya Molodowsky’s poetry, as well as Amy Levy’s, who never fails at breaking my heart. In addition to those, nods to Emma Lazarus and Allen Ginsberg poetry appear directly in the text (in the case of Ginsberg, by way of a school theater project plot device that I am very proud of). To me they are both not just Jewish icons but part of the cultural fabric of New York Jewish life, particularly in the Village.

In terms of other writing influences, I feel incredibly indebted to Alice Hoffman and Naomi Novik, whose work drawing on Jewish history and magic and centering the lives of hungry Jewish women have made a tremendous personal impact on me, and whose successes have created a lot of avenues for other Jewish women to write these kinds of stories. This book also doesn’t exist without Paula Vogel’s “Indecent,” which blew my mind on stage and which I regularly reread. I also owe a lot to Etgar Keret’s short fiction, which I first encountered in high school; “The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God and Other Stories” was the first “cool” Jewish thing I remember reading. That dark, edgy humor and that through line of fabulism first got me excited about the possibilities for speculative Jewish fiction.

Any other upcoming projects?

Like “Night Owls,” whatever I come out with next will definitely be deeply Jewish, feminist in its sensibilities, a little magical, and darkly funny.