Both Sheila Heti’s Motherhood and Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest explore whether motherhood is a woman’s fated destiny.

Though the inquiry is shared, the authors take vastly different approaches in their responses. Heti’s Motherhood is an extremely personal “novel,” one that engulfs both herself and her readers in the question — do I want to have children? — immersing us into her narrator’s tormented inner monologue. Jen George’s debut short story collection does not explicitly ask such direct questions of the self, instead conjuring surreal, emotional, fictional worlds which flicker with the lived realities of contemporary womanhood: adult-ing, sexual trauma, men-as-experts-on-the-female-body, sex, relationship, singlehood, shame, pain.

Heti and George are assured in their shared stance: that child-rearing is a choice, not an inevitability. What they seem less sure of is what becomes of someone who shirks such assumed feminine obligation.

Heti, author of How Should A Person Be, has received much praise and reaction for Motherhood: the text viewed as the pioneering voice on childless womanhood, if only because it seems to be one of very few texts that directly addresses such themes. Never one to conceal her emotions (her first novel advertised as “part literary part self-help manual”), Heti offers her reader complete access to her deepest inner conflict, wrestling with the question of whether she should dedicate her life to her art or to having children, wondering, “Do I want children because I want to be admired as the admirable sort of woman who has children? Because I want to be seen as a normal sort of woman, or because I want to be the best kind of woman, a woman with not only work, but the desire and ability to nurture, a body that can make babies, and someone who another person wants to make babies with? Do I want a child to show myself to be the (normal) sort of woman who wants and ultimately has a child?”

Although such questions are universal and urgent, I found Heti’s ruminating to be solipsistic. Heti manges to take the dire themes of legacy and womanhood and make them completely insular, self-contained. This is because the entire book mostly happens inside of Heti’s head. And yet, as a reader, I found I was most engrossed in the rare parts that happen outside of her consciousness — when Heti is in conflict or in coitus with her partner, when she is considering legacy and trauma with her Jewish mother, when she is in conversation with the numerous authors and publishers with whom she asks pointed questions about partnership and family-making. It is through these relational encounters that we are given access to a female socialization that is sweeping — not just individualized by Heti herself.

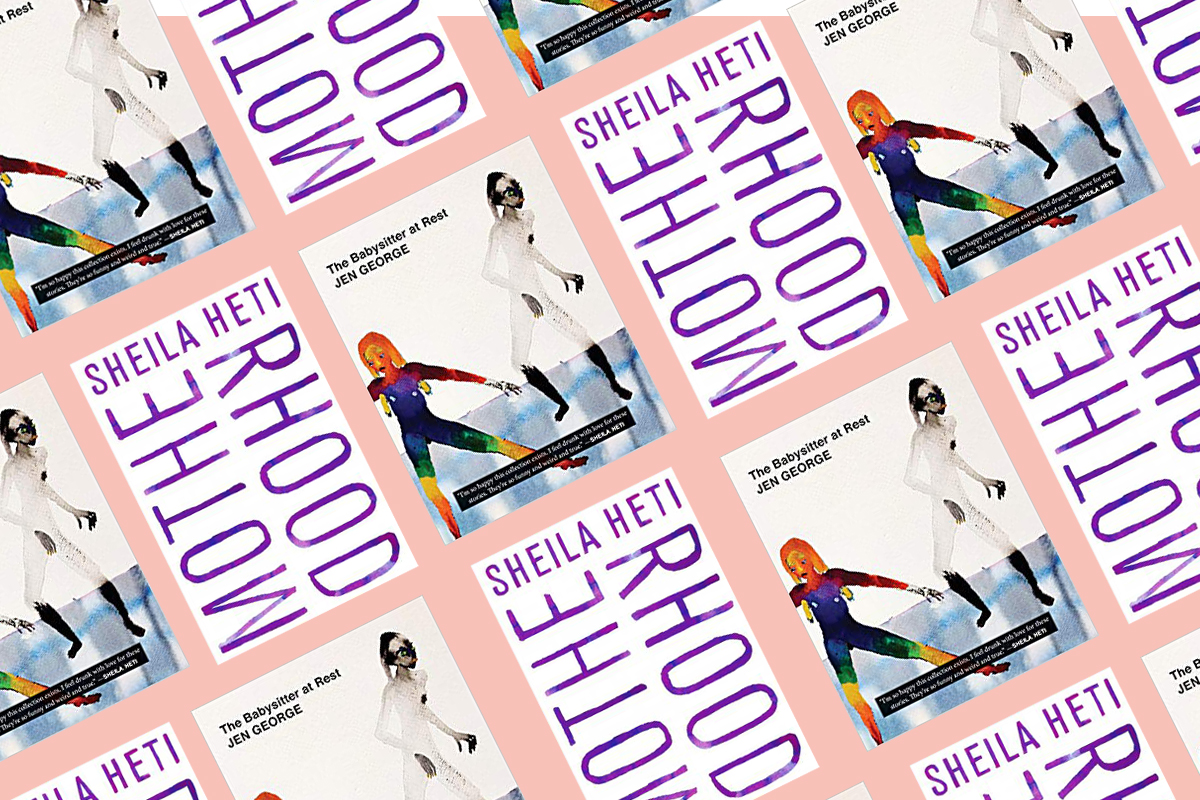

It was Heti, however, who brought me to Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest, a collection published by Dorothy Press in 2016. On the cover, naked, rainbow watercolor figurines dance above a blurb from Heti: “I’m so happy this collection exists, I feel drunk with love for these stories. They’re so funny and weird and true.” I immediately pulled the book off the shelf and began devouring the emotionally naked, kaleidoscopic, frolicking narratives. These stories bring us gorgeously out of our reality and into an altered future: out of our heads and into our bodies, which are revealed to be alive, overflowing, ejaculating.

Whereas Heti takes herself quite seriously, George treats the social constructions of femininity with a rare humor. In her first story, “Guidance / The Party,” a 33-year-old woman is visited by The Guide, who arrives to show the protagonist how to host the party where she will debut as an adult. The Guide states, “Despite your lack of intuition, you may have become aware of the following changes that signal the onset of adulthood: listening to others, doubting everything you think, health problems, understanding of the limitations of time and/or life/living/the individual/experience, failure to believe in the inherent benevolence of the universe, frequent aches- head and otherwise – bad breath (rot and poor digestion), watching someone younger/more attractive be better than you socially and otherwise, crying at kindness.”

What follows is more of an exit from adulthood than an entrance. The narrator bumbles through hosting a party in which she invites only unfamiliar acquaintances (“Social Neutrals”), continually checks the empty oven to avoid social interaction, gets wildly drunk, spills all over her expensive new dress, cries, and makes inappropriate passes at partnered people. No one eats her 10,101-ingredient mole, and she has not accounted for the children that showed up; there are no games or food for them, as are there no non-alcoholic drinks for the many pregnant women.

While the protagonist so obviously fails at adult-ing, the women around her flourish: “‘I’m pregnant,’ says a guest. ‘So am I,’ says another. ‘Both of you are? So are we!’ ‘It was a total shock.’ ‘We weren’t even really trying.’ ‘We tried for three years.’ ‘We’re due on the solstice.’ ‘We’re due on the equinox.’ ‘Either Frederico, ALejandro, Joaquin, Pablo — after Picasso — Paolo, Swordsman, Plallus Maximus, Everest, or Omnipotence, if it’s a boy.’ ‘Pre-natal yoga and grass-fed steak.’ ‘My doctor said I was the tiniest pregnant woman she’d ever seen.’ ‘Walking every day.’ ‘A big glass of water in the morning.’ ‘The weird thing is I’m not even hungry, just blissed out.’ ‘Lucia Frida, Remedios, Compote Rose, Come Hither, Whirling Dervish, Cosmos, Alma, Lil Cutie, Sexually Desireable, or Simone Weil, if it’s a girl.’”

These pithy stabs at cultural narratives surrounding late-stage womanhood are what makes George’s voice unique, and in my opinion, more riveting than Heti’s Motherhood. George’s shortest story is maybe her best, accomplishing the most astute commentary on Heti’s prolonged questioning. In “Futures in Child Rearing,” George narrates a woman attempting to get pregnant with the aid of a futuristic “ovulation machine,” through which she frequently swipes her finger, revealing sarcastic Magic 8 Ball-esque prophecies about her pregnancy attempts. Her first try: “transaction denied,” then “coordinates not found, rerouting.” Later, “You will never be able to pay off your credit card debt.” The ovulation machine’s predictions veer from cruel perceptions on womanhood — “Get outside and/or a life” — to exposing society’s constraints on motherhood: “Insufficient funds.”

Ultimately, it is George’s ovulation machine that manages to say explicitly what Heti’s narrator can never directly admit: “This is torture.”