“Welcome home,” the rabbi gleefully offered as I arrived early to help set up for Rosh Hashanah services at Manhattan’s Jacob Javits Convention Center. A mental image of the number 400 immediately flooded my mind and my eyes watered.

That’s how many cots, allotted 5’x8’ each, give or take 50, I’d guess the event hall could hold if converted into a hurricane shelter like those I had just helped to set up and staff in Austin and Houston. The entire Javits Center would easily hold thousands, and I guarantee someone on New York’s emergency management team has that number calculated precisely.

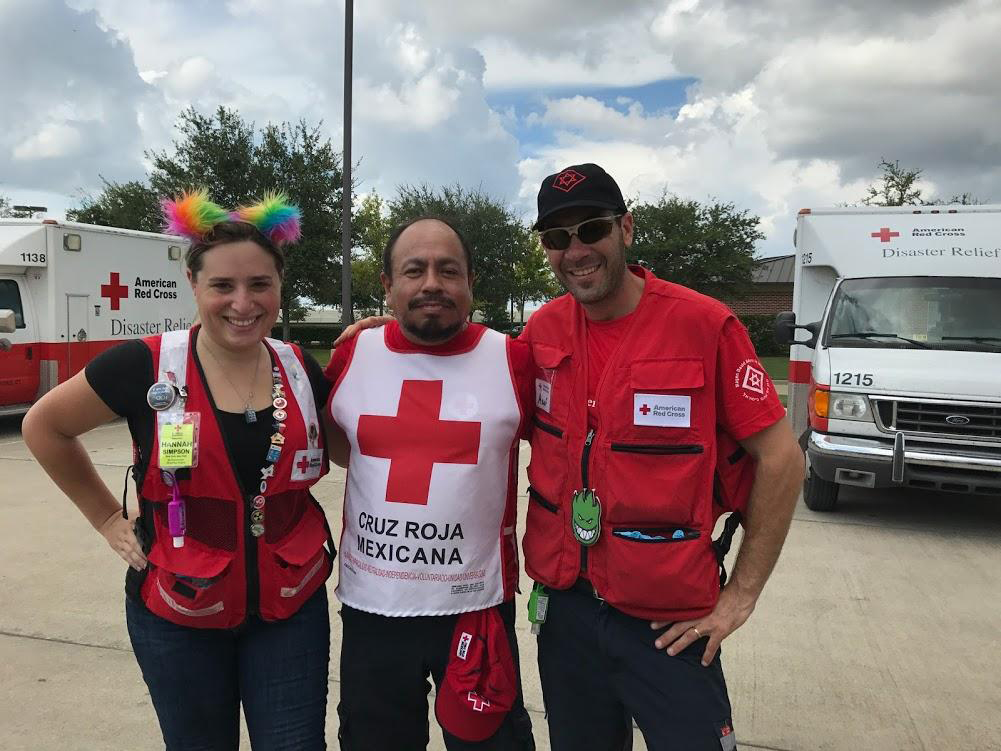

The rabbi was noting my return to New York after three and a half weeks volunteering with the American Red Cross through and following Hurricane Harvey. I soon learned the whole temple had followed my social media updates throughout that experience. “Welcome home” meant to welcome me back to my residence and congregation, but it jarred me nonetheless. I could come home, but tens of thousands of people in Texas (and by then, Florida) were literally calling convention centers like this one, school gyms, or industrial warehouses their new “home.”

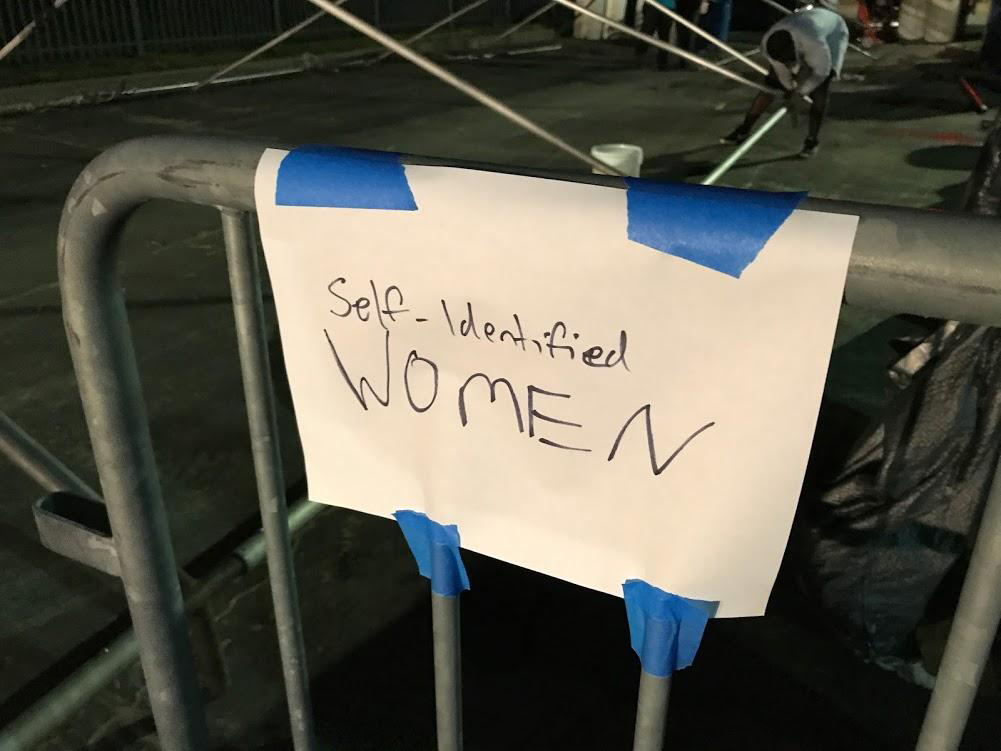

I traveled to Austin on an invitation to deliver a guest sermon for the annual Interfaith Pride Service—to talk about life from the perspective of a Jewish transgender woman. I had plans to stay through the parade weekend, but that was cancelled along with my outbound flight as the storm loomed. A local news network reported the Red Cross was recruiting to scale up in Austin for coastal evacuees. How better to spend my pride than by volunteering in a state that had just narrowly failed to pass laws dictating which restrooms I must legally pee in?

#ATXPride by 24hrs of #HurricaneHarvey @CenTexRedCross service!@GregAbbott_TX I’m #trans & concerned about humans BEING, not humans PEEING! pic.twitter.com/pjA0VidBXk

— Hannah Simpson (@hannsimp) August 27, 2017

That first stormy night in Austin, a Shabbat by coincidence, was the hardest. People slept on whatever blankets or air mattresses they could bring or buy at the local big-box; we had few other supplies yet besides plenty of food and water. It was all we could do to pass the time, talking well into the night with anyone who couldn’t sleep under the howling winds, anyone who was still charged on adrenaline after driving themselves and their families inland hours before the roads flooded.

To be clear, we had it easier in Austin, mostly tending to those who left early. The heroism of the teams of trained experts and amateurs alike, like my friends who went out rescuing neighbors by boat and jet ski around Houston, remains beyond words.

I couldn’t help but think about the upcoming holiday of Sukkot, this holiday we Jews have to intentionally relegate ourselves into temporary huts like the Israelites dwelled in during their years wandering the desert. It’s an unprecedented season when so many across these states, and now Puerto Rico, are shelter-seekers out of necessity. It makes you wonder what’s really temporary or permanent in our lives and our identities.

We built for them a sukkah, a temporary space, even within buildings chosen for their sturdiness. As the storm passed, the services the Red Cross could offer became more and more robust. More evacuees arrived, and in conjunction with FEMA and other agencies, the bureaucratic cogs of recovery sprung into life. I spent hours reading stories and clowning around with the kids. We built for them a sukkah, too, a temporary sense of security while their parents faced the difficult road ahead.

Specialized health care providers started coming through. An older woman returned to our shelter in agony, having had teeth pulled free of charge by a local dentist. Safe bet it was her first dental work in ages. I borrowed two hula hoops from the kid space to tape across her cot, creating a frame, then draped a towel above. I built for a her a sukkah, a small head canopy to offer the slightest extra dignity and privacy as she recovered.

I inflated a long clown balloon, writing in Sharpie, “Please come help me” on each side. Weak and exhausted as she was, she could wave it lying down rather than sit up to signal us. I wonder if that counts as her lulav?

To paraphrase the ineffable Dr. Horrible, Sukkot is about destroying the status quo ever so symbolically, to remind ourselves that the status is not quo. If three “500-year” floods can arrive in as many years, so can single-payer health care, substantive gun control, and immigration reform once we refuse to take “impossible” for an answer.

Volunteering these few weeks in disaster relief was transformative. Three girls from the shelter and their mommy just called me last night, and despite all they have been through, they just wanted to ask how I was doing. They extended their sukkah back around me by FaceTime, helping me feel a little less guilty for returning to my own dry home.

Sukkot challenges us to think outside the usual boxes since our people first wandered toward the Promised Land. I took pride that Israel, our modern collective home as Jews, deployed relief workers over 7 thousand miles away to Texas from its own Magen David Adom, “Red Shield of David,” agency, in no small part because we as a people so actively remember our own times of uncertainty.

If you can’t make it to the actual areas affected, you can still give by material possession. Buy an airline-style duffel bag and fill it with three shirts, two pairs of pants, undies, three bottles of water, one roll of reflective duct tape, and a nice waterproof LED tactical flashlight with batteries. (Don’t skimp on the flashlight, I mean it!)

Write your full name on a luggage tag so the evacuees know exactly whom to thank, and you can even pen, “With love, for the hurricane / fire / tornado / zombie apocalypse survivors” on the outside over a few strips of the shiny tape. Get creative, then stick it right at the top of your own closet. The survivor you gifted might just be yourself.

Bring every sense of yourself into a sukkah this week—physical or metaphorical—or go build someone else’s, especially when it feels inconvenient or impossible. Impossible is no longer an option.