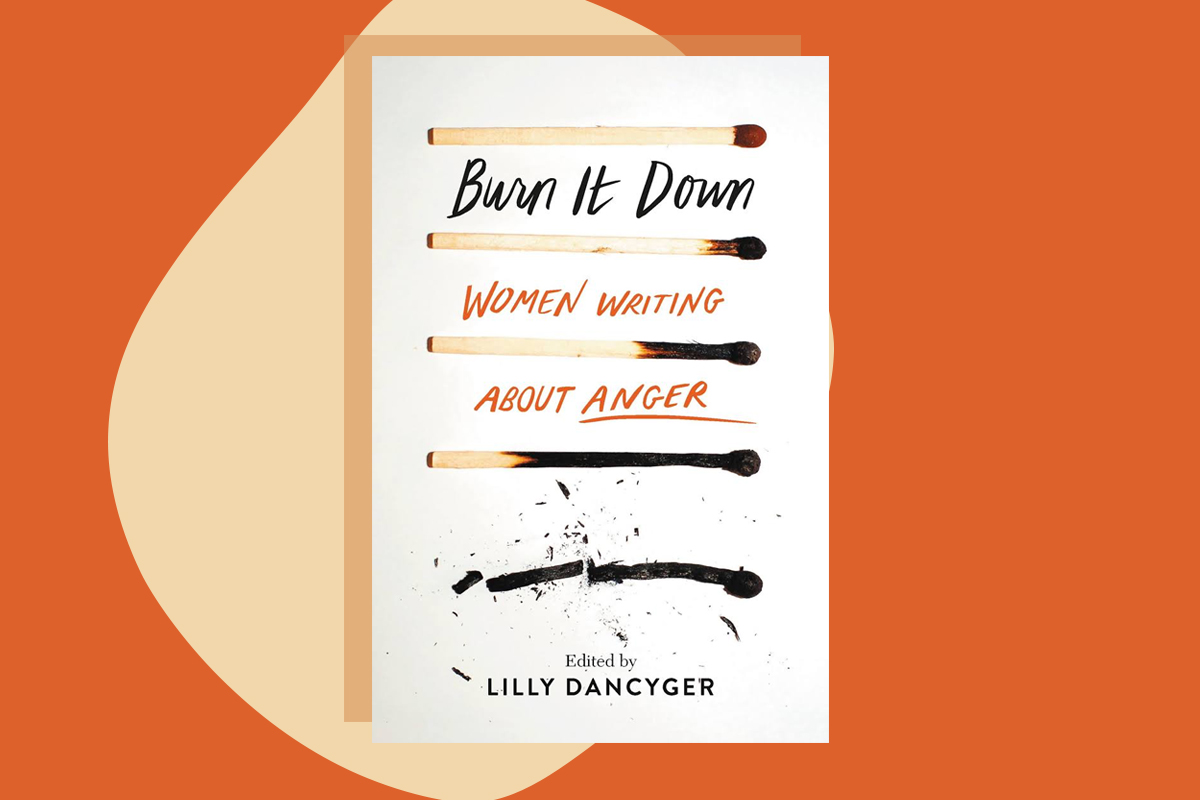

At the start of Burn It Down: Women Writing About Anger, the editor, Jewish writer Lilly Dancyger, writes that she wanted this book to “be a place where our anger could live, a place for us to take up space after generations of being told to shrink, to rage after a lifetime of being told behave.” The result? A powerful collection telling tales of anger.

Dancyger explained to Alma that putting this together was a lot of work, but 100% worth it. “It was also so healing and soothing for me to immerse myself in so much powerful, beautiful anger during the last couple of years when there’s been so much to be angry about every day, and hopelessness is so tempting,” Dancyger says.

Over e-mail, we asked Dancyger and three of the Jewish contributors to the anthology — Marissa Korbel, Erin Khar, and Sheryl Ring — to talk about anger, catharsis, and — ’tis the season — Yom Kippur.

🔥🔥🔥

The subtitle of the anthology is “Women Writing About Anger.” What does that mean for you?

Sheryl Ring: For so long I considered it inappropriate for me, as a woman, to be angry about anything. I remember sitting with my therapist years ago talking about something, and my therapist asked me whether or not I was angry, and I just said, “No.” I wasn’t supposed to be angry, because women aren’t supposed to be angry; that’s how I was raised, just like so many other girls. Now, looking back, that makes me angry! So for me, now, being a woman writing about anger is a deeply subversive act in a world where anger is considered “bitchy” or “male.” Angry women are women who aren’t necessarily docile or domestic or pliable, but instead fierce and independent and present in our own lives. We are our own whole people, and anger is a part of being whole, but it isn’t negating to our womanhood.

Marissa Korbel: Anger, particularly women’s anger, is so much the zeitgeist at the moment. From Greta Thunberg’s addressing the UN on climate change to women reclaiming Medusa, rage is really up for a lot of women. I know that in the last four years (since the 2016 primaries), I have personally been more in touch with my anger than I had been in any other part of my life. Between the misogyny of leftist bros, Brock Turner, Trump’s election, #MeToo/#TimesUp, the continuing disaster of the Trump presidency, the Russian interference, Congress’ refusal to act in the best interest of our country, the Kavanaugh hearings… when I list it out like that, it’s no wonder that I am so angry and that so many women are furious right beside me.

One thing that’s really important to me about anger is that it is a motivator, where depression, sadness, and some of my other emotional responses (dissociation, overwhelm) can be the opposite. I used to be scared to get all the way angry because I felt out of control. Now I embrace it because I know that energy is going to move through me, and then move me toward action. That’s important.

🔥🔥🔥

What does catharsis look like for you?

Korbel: I tend to think of catharsis as related to crying. So I think if I’m angry and there’s tears, I’m more likely to have that feeling of having completed something or having moved someplace else emotionally. I also think of catharsis as related to creativity, to art, to experiencing something and processing it and getting to make some peace with the largeness of it. When I make art out of something that is large and overwhelming and scary, and then that art is sent out into the world to move through other people’s minds? That is incredibly rewarding and cathartic.

Ring: Catharsis is, to me, a privilege which too many people in our country deserve but don’t have. Just on a macro level, in today’s world it seems that we as a society lurch from injustice to injustice, and that each [injustice] is, by itself, the kind of thing that we should be angry about. There are children dying in dog cages in this country because of the color of their skin. Nineteen Black trans women in this country (that we know of) just this year have been murdered for being Black trans women, and in 44 states their gender identity can be used at trial as the legal cause of their deaths.

On October 8, the day the book comes out, the Supreme Court is considering whether it should be legal to fire you for being LGBTQ, or for not wearing a dress or a skirt if you’re a woman. These things should make us angry, and we shouldn’t stop being angry until they stop. In this country, if you’re Black, or Brown, or non-binary, or disabled, or facing sexual harassment or assault, you don’t have the privilege of catharsis because you don’t have the privilege of anger: to be angry is to be seen as a threat. For me, as a white woman, I’m fully aware that I have the privilege of my anger. Yes, I’ll be seen as unladylike and bitchy, but I won’t be seen as a threat. So actually, I’d argue that right now we shouldn’t have catharsis. We shouldn’t want catharsis right now. Those of us who can be angry should be, because too many among us can’t be.

Lilly Dancyger: I love a good rage cry. Seriously. Marissa’s piece in the book about rage tears is so great, and explains the phenomenon in such interesting ways that made me really think deeper about why I cry when I’m angry. But whatever the reason, it feels good to let it out. I also usually feel better after telling someone I’m angry with that I’m angry with them and why. Then I can move on, rather than stewing.

Erin Khar: Catharsis is a process. That process begins with telling the truth which is why our voices being heard matters so much.

🔥🔥🔥

Are there Jewish things/rituals/traditions you do to process your anger?

Khar: I have only been to a mikveh once, before my wedding. But the act of immersing in running water as ritual, as a means of marking the end of a period of mourning or a new beginning, that resonates with me. Water is a tool I use frequently when I’m processing emotions, from bodies of water, to a bath or shower, or even cold water running over my hands in a sink.

Ring: My Jewishness is such an integral part of my identity. I’m a legal aid lawyer because I believe that tikkun olam should be the guiding principle in my life. God knows I don’t always succeed, but I do try. What’s been hard, as a trans person, is finding a Jewish community to accept me. Thus far, most congregations I’ve attended have taken the position that transness is a sin. And as much as I’ve struggled with this, I refuse to believe that who I am is somehow wrong.

One of Leonard Nimoy’s favorite sayings that made it into the Star Trek canon came from the Jewish tradition: “Infinite Diversity in Infinite Combinations.” I believe in that with all my heart. I believe that who we are is, in the end, all we have. And so for me, tikkun olam is more than just a guidepost for my life — it’s my response to my anger about everything that’s wrong with this world. Being angry is a good starting point, but that’s all it is. We’re angry, but what are we going to do about it? Tikkun olam provides the answer.

🔥🔥🔥

The book comes out the day before Yom Kippur, which is a holiday all about repentance and forgiveness. When you think about the people or things that have you made you the most angry, is it possible for you to forgive? For them to atone?

Korbel: I think those questions are in reverse order. I really despise this notion (often pushed at and on women) that we should forgive our abusers “for our own good,” as though we can’t be fully healed until we let the people who violated us off the hook. I wholeheartedly reject that idea. Healing is a process, and I will probably never be “done” with it, but it isn’t dependent on me forgiving anyone or deciding that it’s okay that they failed me, hurt me, used me, etc.

The closest I have come is to recognize the humanity and complicated psyche of everyone, including the people I’m angry with, or have been abused or neglected by. It’s not the same as forgiving them for what they did that hurt me. But it allows me to carry it differently. There is no such thing as a bad person, not fully, not even the worst people I can think of are wholly and completely bad. Everyone has lightness, goodness, and things that other people love about them. But that doesn’t cancel out their darkness, sadism, or responsibility to express their shadow parts in a way that isn’t harmful to others. And when people don’t do that, when they hurt other people with their acting out, that isn’t something they just get to be forgiven for. At least not by me. Not without some sort of atonement or repair.

That’s why I think the questions are in reverse order. I can and have felt forgiveness for people who apologized to me, who offered some repair, and who atoned in some way for their actions. Yes, it is possible for me to forgive at that point, but it is still about me and my agency.

Khar: You know, I think that there are different types of anger. When it comes to individuals who have hurt me or angered me, forgiving them is only going to benefit me. Whether or not they atone is not my business or responsibility. And forgiveness doesn’t mean those individuals continue to have access to me, but rather it relieves me of carrying anger. Then there is the type of anger I have against institutions and systems of oppression that have been in place for years and years. I believe in holding those that uphold oppression accountable. And I’m not sure I need to forgive those systems and institutions. Rather, that anger fuels action and change.

Ring: The person I think about most when you ask me this is my mother. I came out to her when I was 8, and the next few years were pretty hellish for me. There was conversion therapy — she didn’t call it that, but that’s what it was — everything from waterboarding me with vinegar to trying to “pray the trans away.” When I was 16 and suicidal from being forced into a malehood that wasn’t me, she told me I should go ahead and kill myself so she could be rid of the shame I brought upon her. Later, I found out that she sat shiva for me when I finally transitioned. So yes, I’m angry.

Strangely, I forgave my mother some years ago — not because I want to, but because I had to. I’m still angry with her. But I’m not angry for what she did. I’m angry because she won’t atone, even though she could. She’d rather pretend she never had an oldest child than accept she had a daughter. No matter what I do in my life, to her it doesn’t matter because I’m her oldest daughter and not her only son. That’s a heavy thing for me to carry.

Dancyger: I can’t speak to whether it’s possible for them to atone, because I don’t think that really has anything to do with whether or not I forgive them. I think atonement is something internal, grappling with your own misdeeds. So that’s between them and their god, I suppose. And I think forgiveness is powerful, but it also became a lot easier for me to forgive when I learned that forgiving someone doesn’t mean you’re not allowed to be angry anymore. I can forgive the person and still have every right to my own emotions about the ways they’ve wronged me, and the ways those wrongs have impacted my life.

🔥🔥🔥

There’s a certain stereotype of Jewish women being loud/overbearing/nagging, most often presented in a negative way. Is there a way to reclaim this — Jewish female loudness?

Khar: It comes from a place of inherent misogyny. I say we stay loud, we don’t back down, we let our voices continue to be heard. I am not about staying silent any longer.

Ring: Oh definitely — and it’s by being loud and overbearing and doing it for good. I’m a lawyer, so I know how to be loud and overbearing for a good cause. But seriously: Sometimes being loud and overbearing is the only way to make people listen. On issues like climate change, timidity will get us nowhere.

Dancyger: I have never seen Jewish women’s loudness as a negative thing! I’m lucky to have grown up with some really incredible strong, loud, opinionated, hilarious Jewish women, and have always seen that quality as a strength.

🔥🔥🔥

What are you most angry about today?

Dancyger: It’s hard to choose these days! All of the shocking and horrific injustices of living in 2019 kind of swirl together in my stomach into an all-encompassing rage. Children in cages, climate change deniers, rapists in the White House and on the Supreme Court, circular conversations about the “electability” of female candidates, how many Americans have been brainwashed by Fox News, people getting rich off of the opioid crisis, racist cops, Amazon not paying taxes, the sound of Trump’s voice… so, so many things.

Ring: What makes me most angry today is how easily our society turns a blind eye to the suffering of underprivileged people in the name of “moderation” or the “marketplace of ideas.” We, as a society, want to make sure that “both sides” are heard when it comes to issues like transphobia, sexism, and racism — and the result is giving power to transphobes, sexists, and racists and taking it away from people fighting transphobia, sexism, and racism. The worst part is that the people at the intersects of those bigotries have it the worst.

Khar: The blatant racism in this country and the treatment of refugees at our borders. I am angry that there are so many humans who have no humanity.

Korbel: This morning, and pretty much every morning for the past three years, I’m angry about my country. I’m angry that people are so brainwashed by Fox News. I’m angry that they voted in a misogynist pig president. I’m angry that Mitch McConnell doesn’t allow the Senate to vote on anything. I’m furious about the family separation policy, and terrified about what is happening to those children. I am mad at all the benign sexism on the left, and all of the blatant sexism on the right. I am furious with the patriarchy, with the framework I inherited that made me value my attractiveness to others over my own self development and esteem. I’m angry that men continue to make, enforce, and play by rules that favor themselves and hurt others. I’m disgusted by the sexualization and fetishization of women and girls, and just thinking about my daughter having to face this down is exhausting and terrifying and maddening. I’m mad about a lot of this on any given day. I carry it all with me. It’s no wonder I wrote for an anthology called Burn it Down. I live in that place right now. I hope one day, in the ashes, we build something better. I hope one day, when the smoke clears, I can feel something different in the morning.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.