In her second book, Wandering Dixie: Dispatches from the Lost Jewish South, writer Sue Eisenfeld takes the reader on a journey while she travels to and researches lost Jewish communities. Lost communities in Eisenfeld’s book include places where it seems like the only part of Jewish history that remains are old temples, as well as cities where people may be surprised that Jewish communities thrive. Wandering Dixie is not a history book, but rather a memoir where Eisenfeld’s connections to the subject matter, both as a Jewish woman and as a distant cousin of murdered Jewish Civil Rights activist Andrew Goodman, engaged me as a reader and helped to illustrate why documenting these communities is an important endeavor.

Over a four year-period, Eisenfeld, who is from Philadelphia but lives in Virginia, traveled to nine different states and visited Jewish history and Civil Rights sites in each. Eisenfeld talked to me about those lost communities, Jewish Confederates, and the impact that this research has had on her personal life.

As a Jewish woman originally from the North, what drew you to want to write about lost Jewish communities in the South?

I didn’t really set out to write about this so much as this topic found me. When I was in Richmond one year, I happened upon the Hebrew Cemetery, and in the middle of it was a Confederate soldier section. At this point in my life, I just had never heard of Jewish Confederates, and the idea of Jews fighting on the side of the South, given that we had escaped our slavery, which we commemorate every year at Passover, just seemed so contradictory to me. This happened in 2006, and it really gnawed on me for years until I started writing about it in 2013.

I guess what I decided was not just that I wanted to know about Jewish Confederates, but I wanted to know about where they lived, and why they were in the South, and why they were so devoted to the South. The idea of Jewish Confederates also contradicted with some stereotypical views of the South that I had grown up with, like it was anti-Semitic. I just didn’t know that there was such a long history of Jews living there.

In Wandering Dixie, you weave in your personal narrative with your research of Jewish communities in the South. Why did you decide to share your own experience in this book instead of writing about your findings in third-person like more traditional history books might have?

In my last book [Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal], I traveled through the history of Shenandoah National Park to tell other people’s stories, and I didn’t really tell much of my own story. In this book, I think I had more of a personal stake in the matter. These were my people, essentially, that I was learning about and my history. It caused me to reevaluate my Judaism. So, it wasn’t so much that I set out to write anything about myself, but it just kind of happened that doing this research and going on these excursions did really change me, and I had to include my own journey in the book.

As a creative nonfiction writer, I think, often times, readers become more engaged in the subject matter when the author is part of the story, and I wanted people to become engaged with the subject matter. If I had to be the one leading them down that road, then that was the role I was going to play.

How did your family’s ties to these now lost Jewish communities impact your work and interest in this topic?

Well, Andrew Goodman did impact this work. I always had the memory in my mind of my mom talking about our cousin who was killed and, growing up, I didn’t really know what that was about, but she was very afraid of the Deep South. Once I decided to do this trip, I realized I’d be in Mississippi several times, and I would basically be traversing the landscape where he had done his work and died. I made a point of going there twice actually. His story was one of the things that kind of opened the door for me to look at the South more than from just a Jewish perspective, but also a Civil Rights perspective.

At what point in your research did you realize that African American and white or white-passing Jewish communities in the South are interlinked?

I think that a lot of Jewish people today feel that they have a connection with African Americans in that we both have been through atrocities and periods of trauma and murder. I think that’s true. We both have gone through different traumatic experiences in our history. But learning that Jewish people were slave owners cast that relationship in a totally different light for me. It gave me a new perspective on that relationship. I think, related to that, is the idea that one of the reasons that Jews were able to get ahead in the South and in America is because they’re white or pass for white. So even though there’s always been anti-Semitism, and clearly that’s a problem, we still have the benefit of our whiteness, and that’s a distinctly different experience from what African Americans have gone through.

How did you navigate both researching and writing about white and white-passing Jewish people’s role in the Confederacy, including being slave owners, both honestly and sensitivity?

I think the predominant message I got from my research is that Jews have always tried to assimilate into the dominant culture, wherever they have had to go in the world. Jews have always been kicked out of countries and have generally been oppressed. Wherever they’ve had to relocate, they’ve tried to assimilate to survive. I really don’t think that the Jews at the time, for the most part, had many qualms about slave owning or slave trading, because that is what other white people did. This is an upsetting fact on many levels, and I am not sure that there is a sensitive way to present it. But in all of my writing, I try to present situations in their context.

In an early moment in Wandering Dixie, you wrote about a conversation that you had with your mother on the research that you were doing on Jewish Confederates, who then questioned your research and findings. While some Jews’ reluctance to acknowledge the existence of Jewish Confederates may come from their fears of the Deep South, why is it important to be honest about history even if that history might be uncomfortable?

It’s important to know our history, so we can understand ourselves and our relationship with others better. So we can understand how we got to where we are today and put our current situation in context of history. For example, I was raised to think that Jewish people are always involved with social justice and doing good for the world. It’s really easy to assume that the way things are now have always been that way. Having a broader knowledge of any history informs understanding of each piece of history. I didn’t approach this work as a scholar. I tried to use the work of scholars and amplify the work of scholars to help me understand my experience. I felt like I needed to understand the history to understand the places where I was visiting and what had happened on the soil I was walking on. That, to me, makes life so interesting, to find yourself in a place and to learn what happened there. And that’s really what I was trying to do in the book.

Did the research that you did for Wandering Dixie cause you to confront your own biases?

I was writing this book at a time when the nation was talking more about biases. So, in some ways, I can’t really say that my research and my book caused me to examine my own biases so much that it happened to intersect at a time when things were being talked about more in society. I think that traveling through the history of the Civil Rights Movement helped me to get into learning more about African American history of the nation, intersecting with conversations happening more in my world about institutional racism and white privilege. I think by going on this trip, it really helped me understand what institutional racism really looked like. I would always say that I was against institutional racism, but I don’t think I really understood what it meant. For example, I was at Tuskegee University learning about the history of that university and other Historically Black Colleges and Universities and comparing that experience with Ivy Leagues. I was privileged enough to go to an Ivy League school, and to see the difference in educational opportunities — like formerly enslaved students had to build their own school with their bare hands at a time when the white Ivy Leagues were already up and running for more than 100 years, things just became more crystal clear for me.

In your previous book, you traced the histories of people who were kicked off of their land to create a national park. Between Shenandoah and Wandering Dixie, I’m wondering what draws you to stories of lost histories?

There’s something almost romantic about something that’s lost or about to be lost, so the stakes are higher. It’s like something teetering on the edge that I want to capture before it’s gone, or try to bring to light something that has almost slipped away. It’s almost like if you know something is there and it’s safe and always going to be there, you take it for granted, and when something is more delicate, or could be more easily lost, then it’s more rare and valuable.

In the case of the Shenandoah story, the people in the park are gone, but remnants of their lives are still there. That’s a little different than [Wandering Dixie], where there are still some Jewish people left in these small towns, but in many places there are few Jewish people left, and the temple might no longer have enough funding to survive, and the cemetery might be in disrepair. In these cases, it seems like there might be a way to try to save some of them. They need funding, and they need support. I started to wish that perhaps bringing some attention to these communities would help them. I grew up in Philadelphia where a lot of history happened, and I think I just grew up with the sense that history is really alive, even though the people in the time are gone. And I think that carries over into what I’m interested in writing about now.

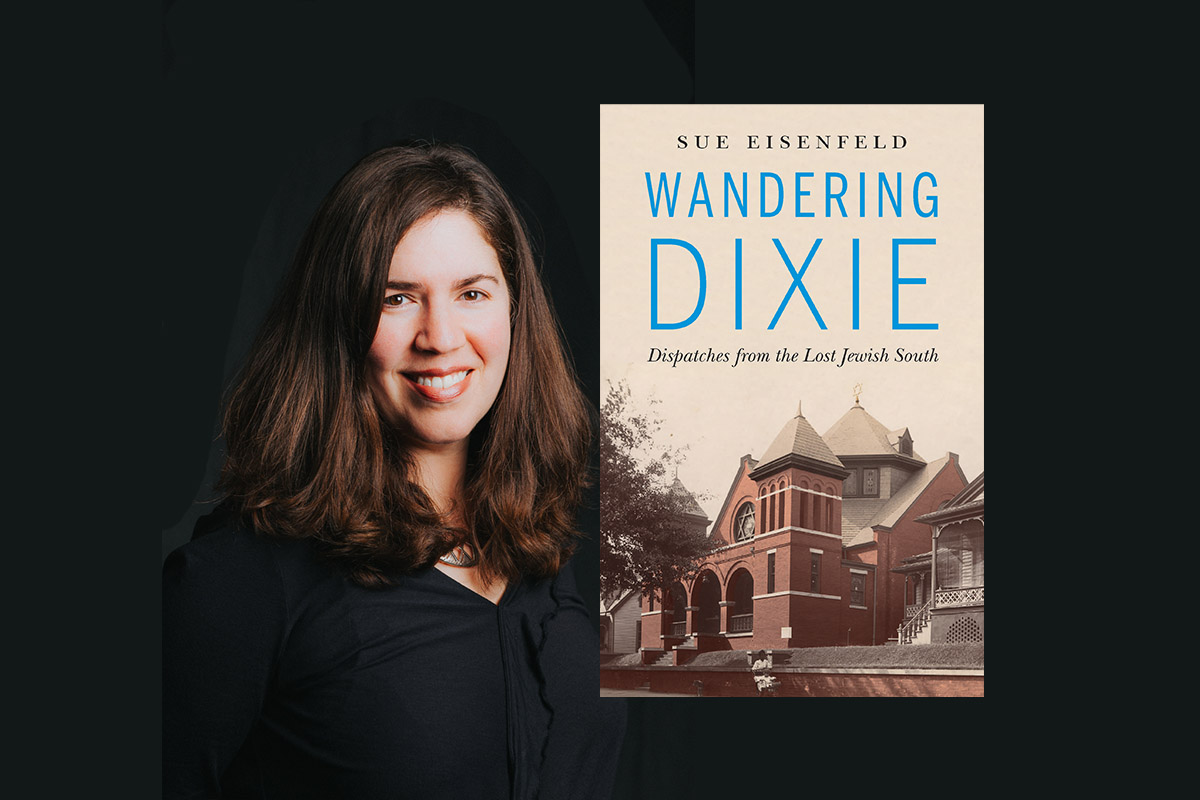

Header image of Sue Eisenfeld courtesy Sue Eisenfeld.