Most of us know the story of the most famous tower in Jewish history: the tower of Babel, in which humans tried to reach heaven, after which God, reacting to that super arrogant move, confounded their speech and scattered them across the world. Jewish artist and architect Daniel Toretsky has imagined a very different kind of tower, one that future generations could use to preserve, rather than fracture, Jewish culture.

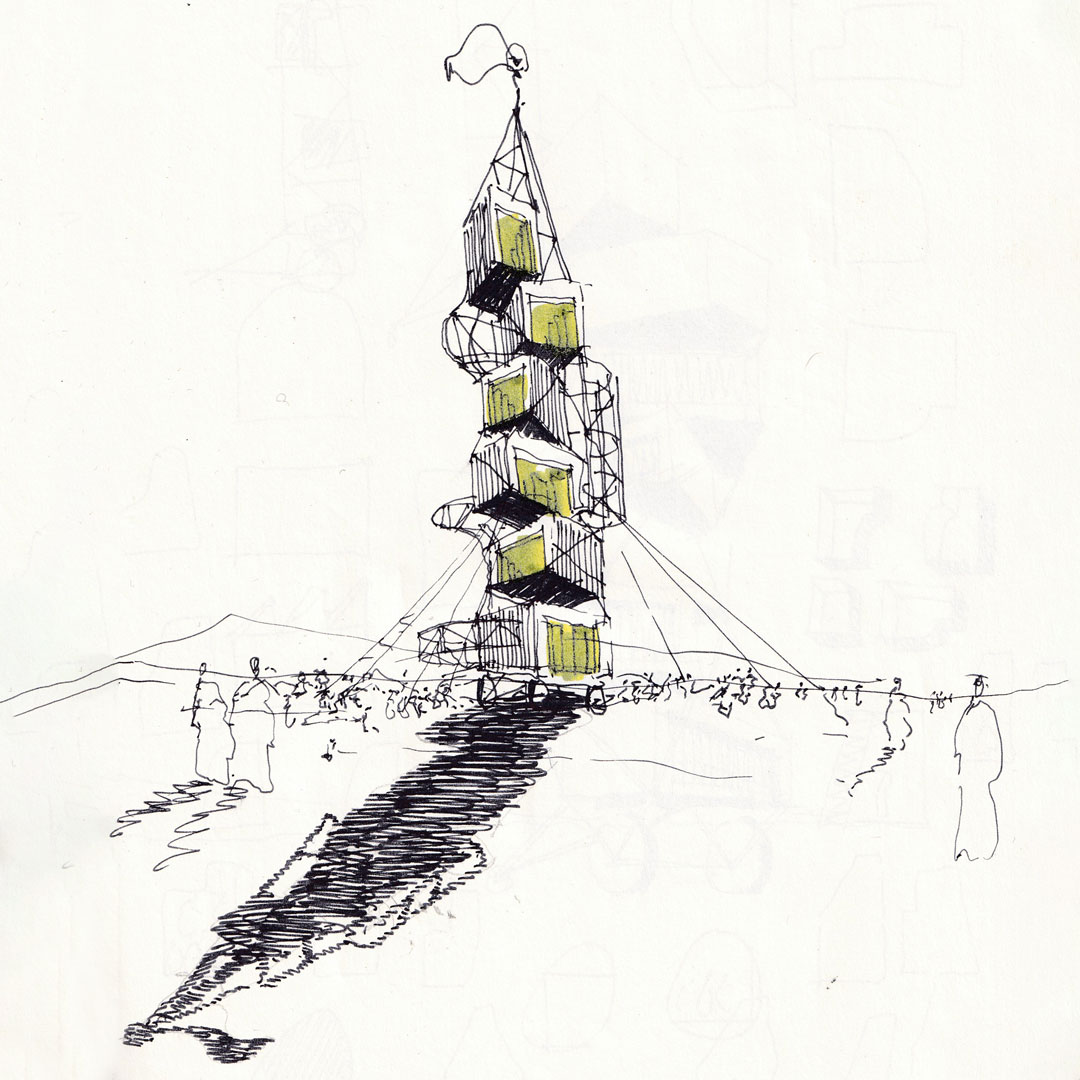

His new project, described by Toronto exhibition space FENTSTER curator Evelyn Tauben as “hybrid sculpture-performance ritual,” is called “Tower of the Sacred & Ordinary.” It responds to our tumultuous times by creating a “roving ritual for the year 2221.” In this apocalyptic projection, climate catastrophe and economic devastation will have chased us from the North American cities we now inhabit. Fortunately, the Jews are well-versed in wandering with all the traditions in tow. “Tower of the Sacred & Ordinary” is portable — Toretsky’s future Jews will “communally [roam] the continent in search of hospitable dwelling places, while schlepping along a monumental tower of memory.”

Perhaps because we have so often been expelled from home, Jews often romanticize a lost, collective past and yearn to return to places that no longer exist, like “pre-war Eastern European shtetl, the Moroccan mellah neighbourhoods of the 1800s, early 20th century in New York’s Lower East Side, Kensington Market in the 1930s or 16th century Safed.” In an attempt to imagine our present as some descendant’s past, Toretsky “asked a diverse group of North American Jewish artists how our current communities might be memorialized by future generations. In their responses, the artists detailed ordinary moments made indelible by circumstance: dividing a Passover meal into takeaway containers to unite relatives during pandemic restrictions; jumping into a lake with Jewish farmers and washing off dirt with a gender-neutral blessing for bathing … These contributions were intertwined and translated into whimsical three-dimensional drawings filling the mobile structure.”

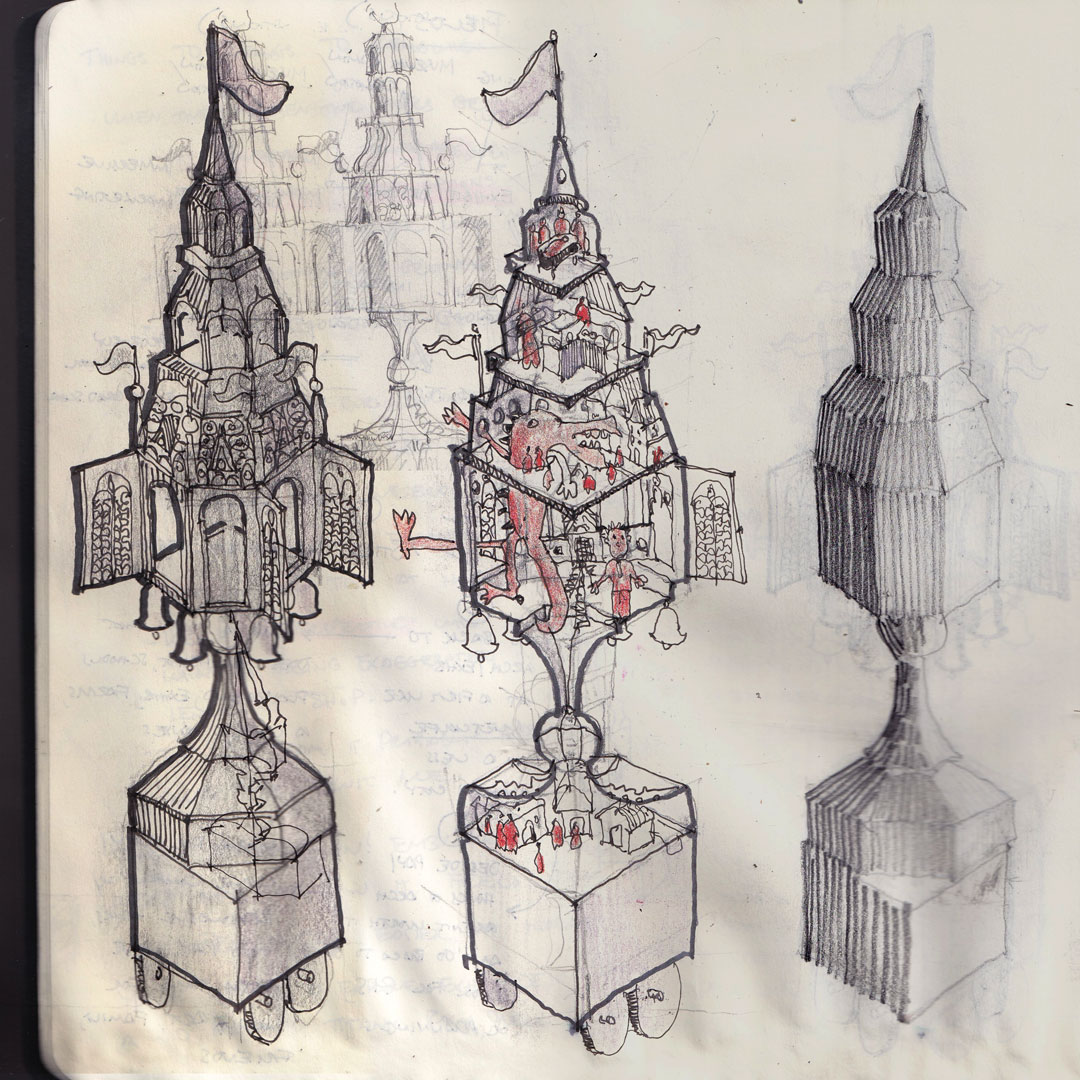

To design the tower, Toretsky drew from many different references: traditional European silver spice boxes, often used in havdalah ceremonies, which were, strangely, often castle-shaped; a mysterious palace on wheels in a now-destroyed Belarussian synagogue mural (more on that later). For now, he’s only made the tower in miniature. But he “conceives of our descendants climbing into a life-sized version of the tower each Saturday evening for a raucous performance of our present-day Jewish lives, re-enacting moments from the sacred to the ordinary” — hence the tower’s name.

I spoke to Toretsky via email about the moments in his life he’d want to preserve for posterity, why “Mad Max” is deeply Jewish, and what historical Jewish neighborhood he’d visit if given the chance, among many other things.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Tell me about yourself, and about the balance of art and architecture in your life. Where is there overlap? Where do they diverge?

I grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, outside of Washington D.C. As a kid I had a model train in my room and couldn’t stop making little models of buildings out of cardboard, so around 10th grade I thought, “Oh! I’ll become an architect.” I looked up how one gets into architecture school and realized that I needed an art portfolio. So I started at the county visual art magnet program, conveniently located in the basement of my high school. This turned out to be a life-changing experience where two fervently dedicated teachers pushed a small group of high schoolers to produce art that was both conceptually rigorous and exquisitely crafted. A few years later, I went to architecture school at Cornell where I stayed for six years and ended up teaching design to incoming freshmen.

In college, I never made a mental distinction between art and architecture — both were modes of interpretation for the world around me, one looking a bit more like a building. But after graduating and starting a full-time job at a corporate architecture firm, the designation between the two became very clear. Suddenly every aspect of architecture had dollar amounts attached to it and I became jaded by the entanglement of architecture in the violent systems of capitalism. I developed an art practice outside work to escape this monetization of space and develop work around interests that I had developed in school (participatory design, diaspora, Jewish space…). Right now I see architecture as more of an artistic medium than subject matter.

How did the inspiration for this particular tower come about? Were you in New York City during the pandemic? I can’t help thinking that the tower’s little scenes remind me of seeing squares of light in tall neighboring buildings…

Oh, I can totally see that — I think all New Yorkers are voyeurs and I certainly became one when I moved to Brooklyn and became enchanted by the split-second vignettes of strangers’ lives as I looked out the windows of the elevated J train. But that was pre-pandemic. My inspiration for this came more from the act of leaving New York and traveling across the country in a pulled trailer with my girlfriend’s family to get her sister safely back to San Francisco. We left on November 5, before the election had been called. Everything outside felt scary and dark and downright apocalyptic (still does!) except we had our little cozy world in tow and that was comforting. So the idea of schlepping your home through Armageddon came from that.

The other moment of clarity was watching “Mad Max” (the good one, with Furiosa) for the first time recently. The premise of the movie felt deeply Jewish — escaping slavery and traveling across the desert in search of a prophesied safe haven — and I was fascinated by the way that the vehicles became palimpsestic records of this journey.

Lastly, there is a book by Miriam Lipis about all of the portable homes found throughout Jewish ritual. I always come back to this as a point of inspiration. She talks about how havdalah spice boxes are made in the styles of local architecture throughout the diaspora but then travel to other places, eventually becoming mnemonic devices for lost homelands.

So at some point, it just clicked — in the future we’ll build giant spice boxes to carry our memories and pull them around through the wasteland of climate collapse, desperately clinging to the better world they imply and building more memories into them as we go.

That checks out. When did you first encounter a havdalah spice box? Were you fascinated right away?

I probably encountered the spice box in the glass display cases of Judaica that you see in the back hallways of synagogues and JCCs. I grew up celebrating havdalah most Saturday nights and it was really embraced in the Reconstructionist movement that my family was a part of. But instead of using an ornate architectural spice box, we would just use whatever jar of cinnamon was closest to the edge of the spice shelf — and that worked just fine!

I wasn’t fascinated by the spice boxes until recently. I used to consider Judaica as just kitschy, which maybe it is, but even as ornate as many Judaica objects are, they recede into the backdrop of cluttered Jewish homes and are often overlooked. In some ways, it is good that we can perform a Jewish ritual without an ornate, fragile, expensive object. But I do have a newfound appreciation for the classic silver spice box and how it can even further elevate an already beautiful ritual.

Can you recount the story of this Belarussian palace-on-wheels that helped inspire this idea?

Well, I actually wish I knew the story. The famous Russian suprematist artist El Lissitzky was fascinated by Jewish folk art during the interwar period. He traveled to the Mogilev Shul in Belarus in 1916 and wrote an article for the Yiddish Language art journal “Milgroim” in 1923 about the shul. He described the painted mural ceiling in detail, remarking on the deep mythological knowledge of the artist. “Milgroim” published color photos of the ceiling, one of which featured a palace on wheels moving across a desert towards paradise. I haven’t seen a definitive answer about what this painting is actually of, so I consider it up to artistic interpretation!

Speaking of moving buildings, did you construct the tower to be architecturally sound? Is such a building-on-wheels actually possible?

If people in the future are desperate enough to cling to memories of a more benevolent past as a way not to lose hope in a more just future, then they’ll find a way to make the tower sound, right?

I buy it! What are some of the most memorable or moving responses to the questions you asked about what aspects of Jewish life today could be preserved and ritualized?

Shabbat was a big theme: One contributor imagined herself as the Shabbat bride engulfed in flames as she lit the candles — connecting everyone in the room (men and women) to a deep femininity. Another imagined a singing circle (tish) after a Shabbos meal — concentric rings of people, older in the center and younger towards the outside, winding around each other like the gears of a watch.

Water was another theme: One artist described the ritual of jumping into a lake with friends after a long week of farm work. Another, from New Orleans, described the ever-present fear of flooding and the effect on the psyche of the whole city.

Nostalgia for lost Jewish worlds was another theme: The same artist from New Orleans lamented the diminishing breadth of Jewish wedding rituals. Another described their experience of being in Chisinau’s Jewish cemetery and imagining the conversation between insects and stones telling the stories of the people buried there. One visual artist described her father’s childhood in the medina of Marrakesh. This world is illuminated by her uncle’s paintings. One in particular depicts a procession to the sea through a bright orange archway and a valley of flowers during the Mimouna festival at the end of Passover.

What would you preserve from your own Jewish life today?

Yom Kippur 2020: My friend invited me over to her roof in Prospect Heights for Kol Nidre. We grew up as family friends at our synagogue in Maryland and had been creating our own gatherings of family-friends-turned-intentional-friends for Jewish holidays in Brooklyn. It was cold but we couldn’t gather inside because of the pandemic. We ate dishes from the “Gefilte Manifesto” cookbook by the light of glowing Nalgene water bottles placed over our phone lights. We propped a laptop on a rusty folding chair and listened over Zoom as the beloved hazzan we had grown up with (Rabbi Hazzan Rachel Hersh Epstein at Adat Shalom) sang the haunting Kol Nidre prayer and the melody settled onto the surrounding rooftops.

Why the year 2221?

Because I don’t know when the climate will officially implode but I can safely say that 2221 is after that date.

If you could visit one historical Jewish neighborhood or time period that no longer exists, which would you choose?

Vilne, around the turn of the 20th century, so I could join the General Jewish Labour Bund.

Same question, but for a period of Jewish wandering, Biblical or historical?

I think I’d want to wander around with Benjamin of Tudela, the 12th century Jewish traveler and chronicler who visited Jewish societies all over the diaspora in Europe, Asia and Africa. I guess I would want to be his personal draftsman of spatial situations.

What are you working on next?

Scaling this project up hopefully. I think building it at a scale where the theaters can hold puppet shows would be so fun and open more opportunities for collaboration.

What is your Saturday night ritual now?

I really don’t have one. Perhaps the lack of repetition is the ritual because there is always something different that comes up, especially as the pandemic waxes and wanes. I’m trying to think if there is any glimmer of havdalah in how I spend my highly secular Saturday nights. Perhaps the glimmer is in savoring the joy of a day without work for one last moment. Or the ritual is thinking for a moment every Saturday that one of these days I should start doing havdalah again.

Can you describe how you imagine a future, apocalyptic Saturday ritual to be?

It’s Saturday night and climate refugees from all over North America have gathered around a dazzling tower on wheels. It’s pulled throughout the week by the masses in search of trees, clean air and universal healthcare. The tower is a haphazard stack of theaters made from salvaged Amazon warehouse ruins and evangelist billboards. It vaguely resembles a palace, or a turret, or a minaret, and it’s painted with bright murals depicting scenes of a long-gone world with seasons. Volunteer actors of all ages make their way into the tower and climb up the trusses into the theaters.

After sunset, they pull back the curtains to reveal scenes from our present world, exquisitely recreated with cardboard and trash. There are scenes of dinners with friends in outer-borough apartments, subway cars with breakdancers swinging from the grab bars, cool ponds with skinny dippers leaping from docks. Each scene is familiar to the crowds watching because it is always these same scenes, and always the same scripts, and yet everyone is still transfixed by the spectacle since it is all they have to remind themselves of a world that existed 200 years before, in 2021, when we still had a chance to change the course of climate change.

The actors reach the ends of their scripts. They transfer the flames from the makeshift tin-can theater lights to braided candles and the whole tower becomes dark except for the flicker of a hundred or so candles. They drink wine (how?) and cast shadows with their hands and strain to smell the traces of sweet spices having long since lost their scent. They sing a song and extinguish the candles in the wine. They close the curtains of the theaters and slowly climb back down the tower. They find their spots along the pulling ropes and start to tug. The tower creeps forwards and rolls slowly through the desert, until next week.

“Tower of the Sacred and Ordinary” is on view 24/7 at FENTSTER in Toronto. An online exhibition event will be presented on August 26 at 3:45 p.m. EDT with KlezKanada, and a multimedia havdalah performance featuring Toretsky’s tower will follow on August 28.