Solomon J. Brager’s work always makes me think, reconsider, examine the world and my internal compass to seek answers to questions I never would have thought to ask. Needless to say, I was very excited to learn they were publishing a debut graphic memoir. I was ready to have my mind totally blown, and I was not disappointed.

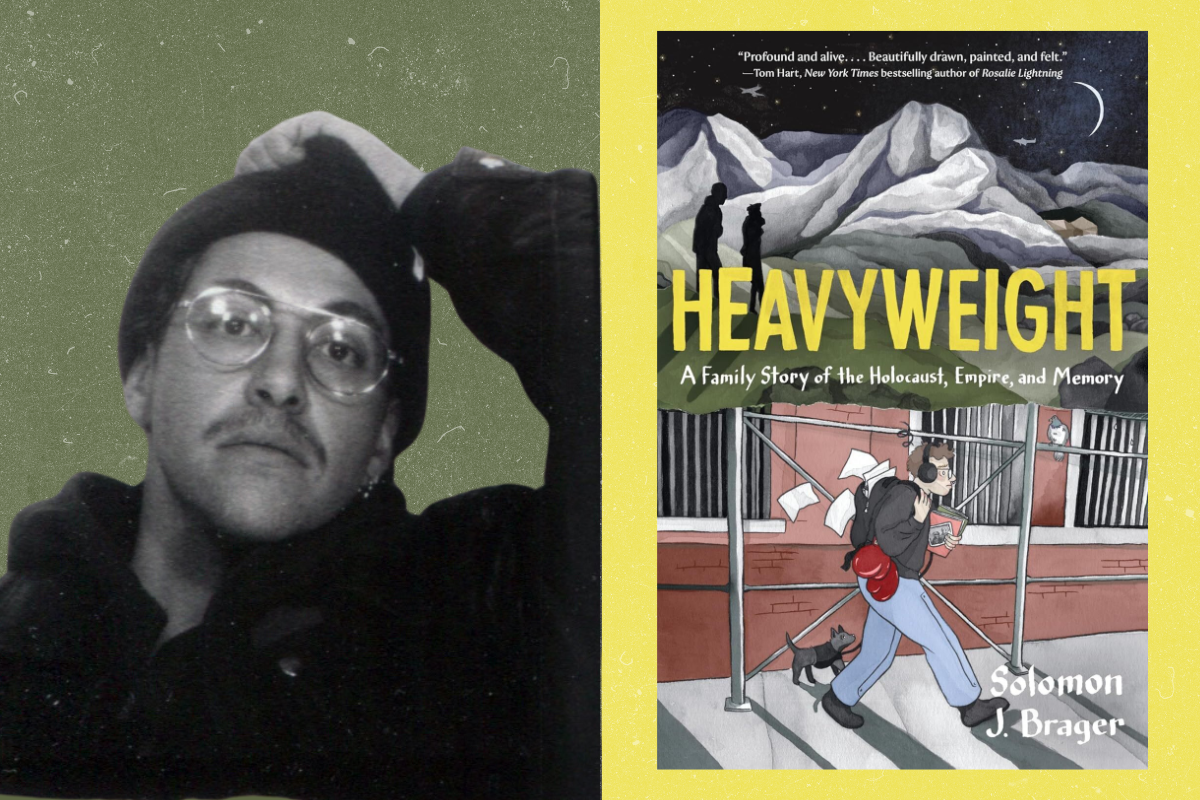

“Heavyweight: A Family Story of The Holocaust, Empire, and Memory” is equal parts memoir and historical account, with every frame rendered in Brager’s signature comic style and jam-packed with archival material and queer radical frameworks of understanding the world and our places in it. It was hard to read at times, and that felt important, too. In telling their family’s story of surviving the Holocaust, Brager does not look away from the complex horrors of the past, and the text asks us not to look away from the complex horrors of the present, either.

Brager and I chatted over Zoom for almost two hours about so many things, including (but truly not limited to!) the benefits and limitations of archival material, what happens when your parents’ dogs almost eat your great-grandmother’s wedding ring, what they hope readers take away from “Heavyweight,” how they took care of their mental health while writing such a challenging text and what’s next on their creative horizon.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’re an artist, a writer, an archivist… you have a lot of skill sets. How did the different mediums that you have at your disposal come together to help you create this book?

I have a very interdisciplinary academic background. My PhD is in Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers. Because Women’s Studies is a very interdisciplinary field, I was working across Sociology, History and Comp Lit.

I ended up, as I say at the beginning of the book, trying to write about my own family in this context. I had that experience of being in a class where everyone was talking really theoretically about something that I had a direct connection to. I had this happen a couple times: I was in a class that was through the Department of German Studies, and a lot of my classmates were from Germany, doing their PhDs in the U.S., and talking about the Holocaust from the context of like, this is an important event in German history. And I was like, yeah, it killed a lot of my relatives!

I took a memory studies class, and we were talking about the Shoah Foundation archives, and we had an assignment where we had to go through the archives. And I was like, it feels really silly to be looking at this archive and pretend that my grandmother’s not in it, right? So I was like, I’m gonna write about her. And then when I started writing about her, I realized that from the perspective of a historian, what she was saying was actually very unsatisfactory. When I turned that assignment in, my professor was like, there’s something here that feels really unresolved on an emotional level in your relationship to your family.

So what sort of familial archival material allowed you to write this project?

At the beginning of lockdown, I had this pile of stuff in Tupperware that I had taken from my grandparents’ house in North Carolina. I was honestly surprised that they still had it.

For years, I have been getting these things in the mail in the strangest ways that were actually kind of upsetting in retrospect. My grandmother had been snipping, like, a family photo out of an album to mail to me, and was just like, “Oh, look, I found this photo!” But I’m like, where did this come from? And it turns out, she’s just been cutting them out of these albums! [Once] she mailed me this medal and was like, “Look, this is your great-grandfather’s boxing medal!” It was literally just in a normal envelope and she’d mailed it to my apartment in New York! This ring [I’m wearing] is my great-grandmother’s wedding ring from 1935. I love my grandmother with my entire heart and she has many strengths, but she doesn’t have an archival brain. This ring was in a Hanukkah care package for me that she mailed to my parents’ house. I don’t go to my parents’ house that often, so there was no indication of when I was gonna get the package. She had put sugar cookies and snacks in there, and my parents have two giant dogs, and of course, they ate this entire package.

And the ring survived?!

I was like, “Nana, the dogs ate the package!” And she was like, “Oh my God, your great-grandmother’s wedding ring was in there! You’re gonna have to go through their poop.” And I was like, “That is an unacceptable outcome!” But luckily the ring was in their crate, just under the dog bed.

Wow. So how did you end up with the Tupperware of family documents?

I had gone to their house in North Carolina to visit and they had these Tupperwares full of crumbling photo albums that were just stacked up. There was no preservation being done around them. They let me take them.

And so I was sitting in my house at the beginning of lockdown with all this stuff. I started by ordering all of this archival preservation stuff, and going through and putting everything in acid-free boxes. And as I went, I realized that I had all this stuff in my home that for years I have been kind of casually looking for in archives, which to this day feels crazy! I probably should put it into an actual archive at some point. But I feel a little… not protective of it, but honestly, just sort of hoarder-y about it. I feel like I’m not done with it. Like I need to be able to keep it for longer before I let anyone else touch it or let it get lost in the labyrinthian archival system.

How does your family feel about the project? Have they read the book?

The response that I’ve gotten has been primarily really positive. My grandfather, who has never read a comic in his life, was like, “Interesting project, great job finding all this stuff about the family. Have you ever thought of writing a novel?” My parents are excited about it. In general everyone’s been really nice and have at least claimed that they are finding it to be thought-provoking.

What is one overarching message you hope readers take away from this book?

Colonialism and historical violence across sites [are] central topics of discussion [in the book], and the complicated messy relationship between victim and perpetrator, and identity, and the things that we accept and are complicit in because they make us feel safe, make us have a sense that we have access to the good life… A critique that I have heard over and over again of anti-Zionist or Palestine Solidarity movements is: you’re hyper focused on Israel, which is antisemitic, like why aren’t you critiquing all these other places? And one of my arguments in this book is that we actually should be talking about all of these places. There’s a panel [in the book] where I’m building one of those conspiracy maps on the wall, like the “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” meme. That actually is how I think we should be thinking about history: All of these sites are connected; the structural frameworks that are being applied are not separate. We need to be able to talk about Israel and the U.A.E. and Sudan and the U.S. and Australia, all of these places, at the same time, and through the same critical lens. That is a message I’m trying to impart.

There’s one line in the book that I personally just can’t stop thinking about: “I keep thinking my family’s tragedy isn’t unique, only specific.” I was hoping you could talk a little about what that sentiment means to you.

There’s a way in which I, on the one hand, am speaking directly to my community of origin — you know, to my Baltimore Conservative Jewish family, and Hebrew school mates, and teachers and rabbis, who really have presented and held onto this idea that the Holocaust is the exemplary historical violence, that there has been nothing like it, there never will be anything like it, it’s incomparable, it stands outside of history, it’s a rupture, it’s unthinkable… and therefore, there’s nothing we can do with it except say yes to anything that survivors or descendants of survivors want, and then also that we can never consider it in relation to anything else that has ever happened. I think that is very politically operative, and it’s very emotionally operative. It puts a wall down between us and everyone else. And it makes a lot of things impossible to imagine.

I want to say to that mode of thinking about the Holocaust in our communities, or families: hey, what if we were able to hold onto the fact that something really awful happened to us in history — and in fact, many bad things have happened to the Jews — and also that many bad things have happened to most groups of people. And that if we can both hold space for ourselves, towards healing, towards repair in our own communities, and then also be able to use that shared experience of violence to find commonality with other groups of people, what would that shift in the way that we are operating in the world?

And then on the other hand, that statement of being specific rather than unique is me reaching out to all of the people in my life whose families have histories of violence, whether it’s the British colonization of Ireland, or the colonization of the Americas, or the Khmer Rouge genocide, or all of the horrific genocides that keep happening in history and that have impacted all of these people that I know and love. It’s me saying, we actually can all talk about the horrible shit that has happened to us. There’s no hierarchy here.

Something else that stood out to me in the book was your perspective on Jews and anxiety, and I’d love to hear more of your thoughts on that stereotype. There’s a panel where you write something like, I’m sick of making the “anxious Jew jokes,” everyone’s anxious, this isn’t about Judaism! And I was like, wow, I feel called out!

Listen… I was definitely calling myself out there, too. I guess the serious question is, if you remove all of these things that are essentially either stereotypes or negative modes of operating that we’ve decided are our identities, then what does it mean to be Jewish? If we’re not sad victim people who are full of anxiety and IBS — which is a trope that I have become very attached to! — then what does it mean to be Jewish? What does it mean to be Jewish without ethnic nationalism as the basis for identity? And then you’re left with some real questions about your relationship to religion and history and law and futurity — like how you want to actually live your life and be in community — that I think are really good questions to be asking.

This project must have been quite emotionally taxing. What did you do while writing this book — or what do you do in general — to take a break and take care of your mental health?

I think I could, in general, be better at that. I don’t know if my partner’s incredibly good either, but he is better than me. For the primary chunk of time in which I was working on the book, we were both working from home, and Charles was also writing a book that is a book of poetry, but engages really heavily with the history of sexology and also with the AIDS epidemic. And so there was often a sheen of darkness over our home, and it was definitely compounded by most of this time being in lockdown, and also being during the protests after the murder of George Floyd. In Brooklyn, during the summer of 2020 and into 2021, there was this long period where it was hard to sleep at night, because there was this constant stream of fireworks and police sirens. So we were both sleep deprived and working on these intense projects. This is all to say, we got very into craft cocktails. I don’t necessarily recommend it… drinking heavily is maybe not a recommendation, but it is something that definitely happened.

We also went to the beach. Living in a place where you can suddenly be in nature is really nice. We’d also go look at turtles in Prospect Park. And then also the big relief valve that I had, especially during that time, was this thing called Dance Church, which was and is again an in-person dance aerobics/dance party class that happened all over the country, and during lockdown they were doing it online. It feels very ‘90s Jane Fonda, like you’re dancing around and the instructor will be like, OK, now we’re doing knee lifts, and there’s a DJ, and they’re like “sweat it out!” and I’m like, I will sweat it out! So we were doing a lot of that in our teeny tiny living room.

Fun! My last question is, do you have any new projects in the works?

Right now for Jewish Currents I’m working on a comic that’s a collaboration with an incarcerated writer — who hopefully will not be incarcerated for much longer, his clemency hearing went very well — named Christopher Blackwell. He is an award-winning journalist, and we’ve been corresponding and working on this project together. It comes out in the fall and I’m super excited about it.

In terms of longer projects, I’ve been very slowly working on a fiction project that is set in my hometown of Baltimore and is a dybbuk story that circles around the cast of a Purim Spiel at a Baltimore Justice Shul that is fictional, definitely not Hinenu. I think there are a lot of people who are doing this and who are doing a great job with it — this isn’t a dearth that I see in the field — but just for me to get to tell a Jewish story that is not about the Holocaust, that’s about contemporary Jewish life, that’s about the Jews that I’m in community with, and imagines a Jewish future that is exciting to me, feels very enlivening. Those are projects that I’m excited to read, and so yeah, it’s exciting to be working on one. And hopefully it’ll be less sad — that’s a goal I have.