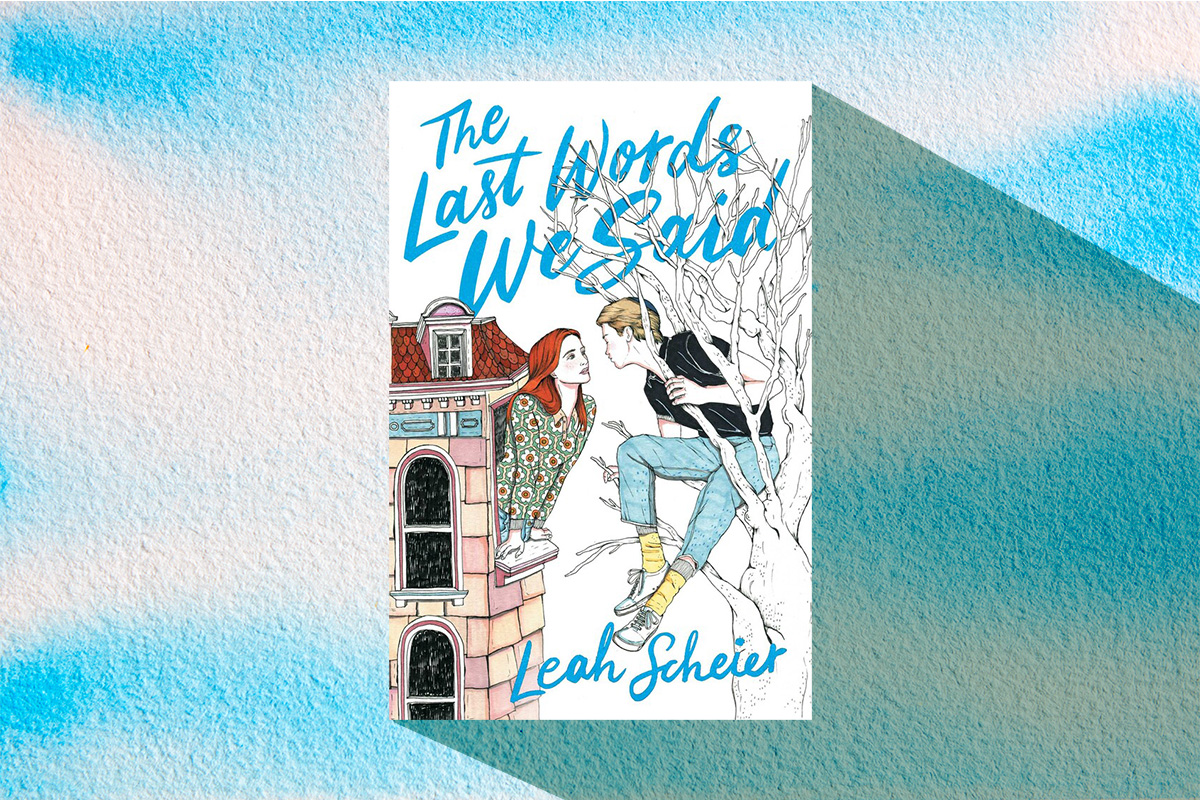

“The Last Words We Said” by Leah Scheier is a recently-released contemporary YA novel about a girl and her missing boyfriend — so one might be tempted to consider this very familiar ground. The book handles grief and love in the long tradition of YA books that tackle the subject. Eliana “Ellie” Merlis is convinced that her boyfriend Danny, who has been missing for nine months, will come back to her. She sees him all the time and has conversations with him. Despite the efforts of the people around her, she refuses to accept that Danny is gone. As the book progresses, the reader learns about the web of secrets and lies that led up to his disappearance, complete with all the emotional devastation that the premise would suggest.

What makes this book different, however, is that its cast of characters is all Modern Orthodox Jews — and this informs much about the way Ellie and her friends process their grief and carry on. Ellie’s friend Deenie has started to “frum out” and become more religious, while her more rebellious friend Rae channels her grief into baking. Jewish religious identity is not technically “the point” of the book, but it is an essential context for how the girls interact with each other and those around them. The expectations of the community and the expectations they have for themselves, as defined by religious Jewish life, are tested throughout in ways that feel unique and profoundly real.

There isn’t much Jewish YA out there. While there has been a welcome and much-needed increase in positive Jewish representation in YA beyond Holocaust literature over the last few years, there are still major gaps. One such oversight mirrors a gap in American pop culture at large, namely depictions of Modern Orthodox life.

Despite making up a significant and growing share of the American Jewish community, Modern Orthodox people are few and far between in mainstream entertainment. While Ultra-Orthodox communities have been something of a trend on Netflix, with “Shtisel,” “Unorthodox” and “My Unorthodox Life” captivating audiences, these are ultimately depictions of a narrow subset of Orthodox life. The breadth of religious Jewish life has yet to be fully depicted in media, and Modern Orthodox communities continue to be overlooked.

Scheier, who is Modern Orthodox and lives in Atlanta where the book is set, found this gap frustrating. “Media frequently portrayed Orthodox Jews only in extremes,” she says, “and the takeaway message was that one could only find happiness and freedom by abandoning one’s Judaism.” Indeed, this tension is often at the core of the Ultra-Orthodox Netflix hits. Whether a character is leaving the community or not, religious Jewish identity is presented in these adaptations as being fundamentally in conflict with a life in the modern world. “Modern Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Jews encourage their children to get a higher education and do not believe in shunning the secular world,” says Scheier. “But because they don’t stand out in the way that Ultra-Orthodox Jews do, their stories get ignored.”

“The Last Words We Said,” like Scheier’s previous novels, pushes back against both tendencies: the tendency toward the extremes and the tendency to avoid religious content. The characters make pop culture references, watch movies, study secular subjects,and date, though the limits of what’s allowed become a major source of tension. In flashbacks and essays, for instance, Ellie negotiates being shomer negiah — avoiding physical touch with non-family members of the opposite sex — while dating. The way this plays out in her relationship with Danny proves sweet, funny and frustrating in equal measure. She also slips up, at times allowing Danny to touch her, and in the fallout she parses both her own messy feelings and the expectations of her family and those around her.

And Ellie is not the only one figuring out her feelings about traditional religious observance. We see that Rae’s small acts of rebellion aren’t a total rejection of the community or Jewish religious identity, and that Deenie’s decision to give up too much of herself in cultivating a more religious identity is challenged (though not rejected wholesale) by her friends. We see characters who have had religious journeys becoming more or less traditionally observant over time. Whereas choices between religious and secular identities are often presented as a black-and-white choice in pop culture, Scheier instead illustrates a kind of uncertainty and fluidity. Individuals in the community are continually figuring out their own places within it and what they believe. The various lifestyles are presented on the page without judgment or any sense that a particular religious choice is “wrong.”

Scheier states that “the easiest part was writing about the Jewish community with love,” and that love is readily evident throughout the book. The book does not shy away from difficult topics like mental illness and divorce, and does not gloss over the frustrations and difficulties that come with traditional religious observance. But the care and love that Scheier has for the community and for the messy, real people that populate it is reflected on every page.

Ultimately, it’s exciting to see a book be so frank about the variety and textures of Jewish life, all while maintaining a rich and compelling story. Books like this open doors — not only for Modern Orthodox representation, but for all flavors of Jewish identity, in all its complexity.