I hate crying in front of family. It’s embarrassing. I want my relatives to think I’m strong and able to cope with things. Yet there I was, not being strong and not coping with things. At all.

On the day I was moving from England to Belfast in Northern Ireland, I started sputtering, “I don’t want to leave.” Between tears, I hugged my nana tightly goodbye and made my way to Stansted airport.

I couldn’t stop crying. On the train to the airport, I wept. Passengers gave me furtive glances and then darted away when our eyes — mine swollen and scarlet by this point — met. Someone offered to carry my suitcase off the train for me because I was that pitiful. At Stansted, I bawled into my Pret sandwich. I sobbed in two different toilet cubicles.

Despite my tears, I had visited Belfast countless times. It’s where my partner is from, and I’d spent plenty of long weekends there before. But moving to Belfast permanently, as a young Jewish woman, was something that I hadn’t prepared myself for.

If you know anything about Belfast, you’ll understand that it’s not best known for a Jewish community. It’s known for Catholics, Protestants, and The Troubles.

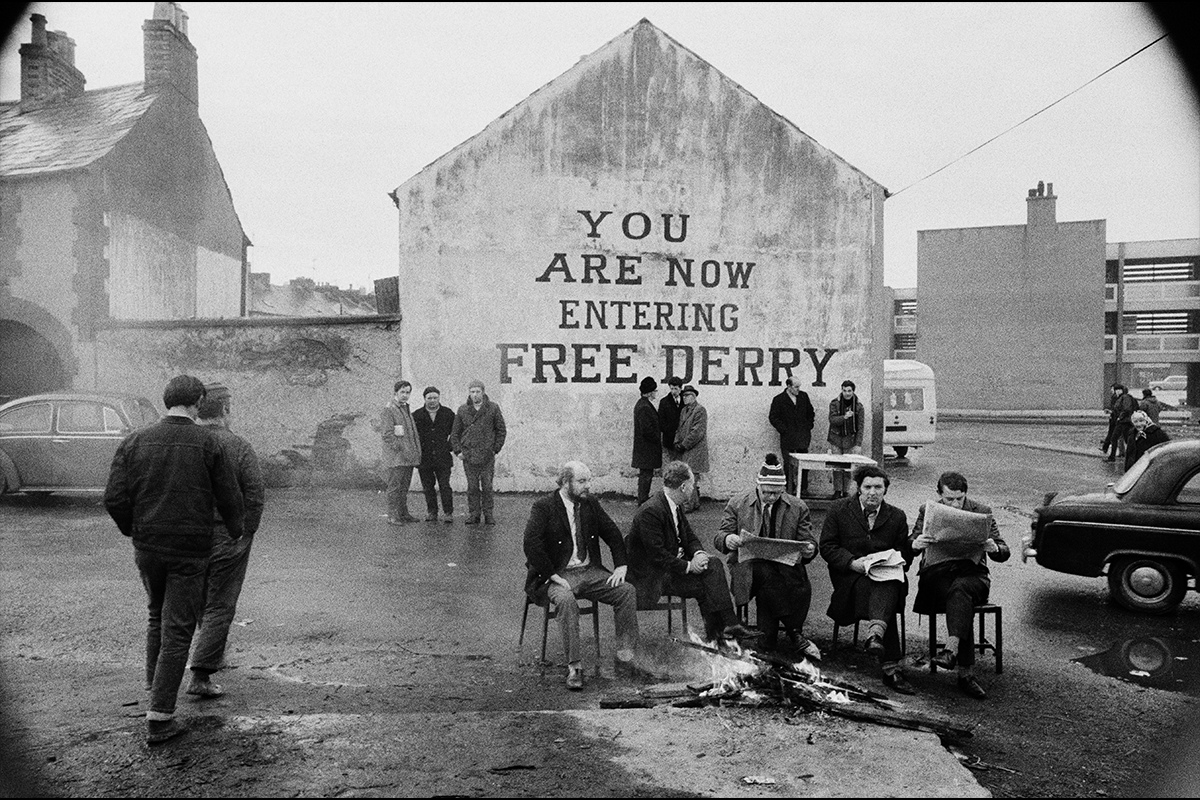

If you don’t know anything about Belfast, without trying to bastardize Irish history in a couple of sentences, I’ll try to explain.

Inspired by the Black protestors fighting for equality in the Civil Rights Movement in 1960s America, Catholics living in Northern Ireland began protesting a long history of anti-Catholic discrimination in the late 1960s. They demanded equal social and political rights with Protestants, who were then the majority in Northern Ireland. Many in the Catholic community, too, were Irish Nationalists; they wanted to unite the North of Ireland with the South so that they were no longer ruled by Britain.

At the time, lots of people in the Protestant community, however, wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom. The nonviolent protests led to violent backlash, which, in turn, led to more violent clashes between the British Army, the police force the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and the nationalist paramilitary group the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

The Troubles — the general term for the long period of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland — began in 1969 after escalating violence. (Not many can agree on the official “start,” as the conflict stretches back many centuries.) The Troubles led to deaths in all communities in Northern Ireland. While there has been relative peace here for over 20 years now, Northern Irish politics and communities remain divided.

The Northern Irish conflict is often compared with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; it’s not uncommon to see the Palestinian flag flying in Irish Nationalist neighborhoods. Similarly, in the West Bank, you might find the Irish tri-color flag flying there.

Where I now live in inner east Belfast, there aren’t many Irish Nationalists. My street, crammed with terracotta terraced houses, is one where you’re more likely to find the Israeli flag flying even though I’m probably the only Jew in the area for miles. The street I live on is a mostly Protestant Loyalist one. So, many people in my community want to remain loyal to Britain in the same way that all Jews — they assume — choose to remain loyal to Israel.

So, where does a Nice Jewish Girl like me fit into this?

Well, not that easily.

The Jewish community in Northern Ireland is small. So small that your bubbe could cook for them all and wouldn’t even break a sweat. There’s only one synagogue which is Orthodox, with an estimated membership of around 70 people. During the Troubles, many in the Jewish community left. And over the last few decades, even more Northern Ireland Jews moved away to study or work and never returned.

When I moved to Belfast, I felt this absence.

Back home, I’d taken my Jewishness for granted. It was something I was able to take out of a box and stuff away again when I felt like it. And, for most of my life, this worked. When I was with my Jewish family in North London, I’d celebrate Shabbat with challah and eat my favorite kosher shop sweets. I’d eat my nana’s honey cake every Rosh Hashanah and had all the comforts that a Jew could want. I could easily put this box away again when I was at my non-Jewish school or out with non-Jewish friends. I was the Jewish Hannah Montana. I had the best of both worlds.

In Belfast, I began craving those comforts. It felt like a part of me was suddenly missing. I was alone this past Rosh Hashanah because I didn’t want to travel during the pandemic. There’s no kosher bakery in the whole country and my supermarket only sells bad hummus. Even though I live on a street sporting Israeli flags, I’d never leave the house with a Magen David around my neck because I’d fear getting verbally — or even physically — attacked if I did. Whilst there have been no reports of physical attacks yet, there have been incidents that suggest antisemitism is rising in Northern Ireland. So, naturally, I’m wary.

Whenever I’ve spoken to Jews who’ve visited Belfast, they all recount to me different versions of the same story. A cab driver, a tour guide or whoever, asks them the same question: “So are you a Catholic Jew or a Protestant Jew?”

Really, this question means: “So, what do you think about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?”

And there we have it. The Northern Irish Jewish experience, crystallized. First, you must prove that you’re Jewish (you’d be surprised by how many people think we’re a made-up cult). Then, your fate hangs in the balance while you think of your answer. You will either become The Good Jew or The Bad Jew. In spaces on my university campus, I’ve felt like I’ve had to prove that I can be both Jewish and anti-occupation. My Jewish identity shouldn’t always have to be a political one, but in Belfast, it is.

I’ve lived here for over two years now. For much of that time, I’ve felt isolated and desperate to return home. Feeling like this, though, has allowed me to reclaim my Jewish identity. This year, I founded Northern Ireland’s only Jewish student society at my university. And it turns out there are more Jewish students here who relate to me than I thought.

Living in Northern Ireland epitomizes, to me, what it means to be a diaspora Jew. Alone, it can be daunting. But when we find others that we can be Jewish with, I remember that despite everything — our history and trauma — I should live proudly as a Jew wherever I want, without fear.