Art Lush’s Instagram grid explodes with color. When I first stumbled across it, the page gave the impression of a stained-glass window: panes of many hues combine to make a varied but cohesive whole. That’s true of many of their individual pieces, too. In one, a half-girl half-snake rides on a turtle’s back; in another, gemstones compose garnet-colored pomegranates.

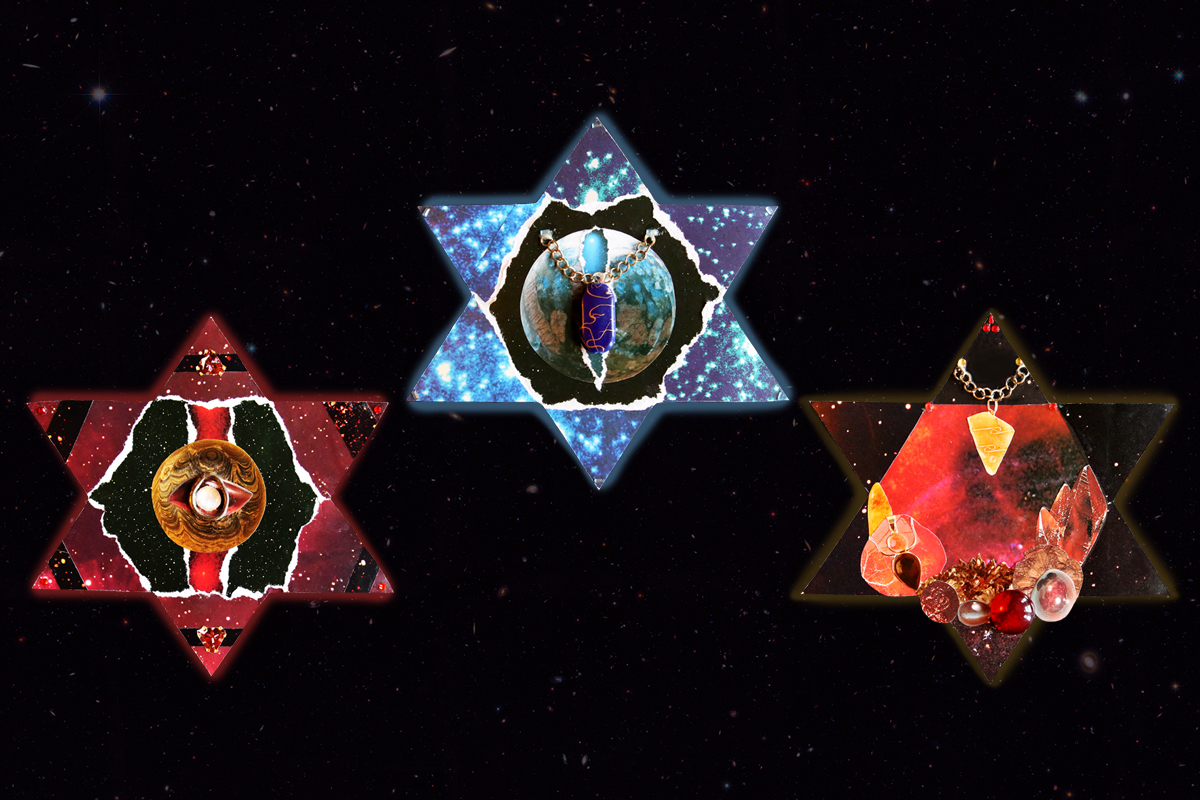

The Edinburgh-based artist describes themself as a “Judeofuturist” and works exclusively from found materials. Many of their images, which are largely collaged, contain queer and Jewish themes. One of the most frequent shapes in Art Lush’s work is the hamsa; they also created a series centered on dreidels. Their captions feature thoughtful musings on antisemitism, transness, history, false scarcity and their own identity, weaving facts about our world in with the art.

I spoke to Art Lush via email about their definition of Judeofuturism, what the hamsa means to them, and their gripes with Instagram, among many other things.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

How did you start working in collage? Tell me about your journey as an artist.

My “career” in the arts goes as far back as early childhood, as I was fully immersed in theater, dance and performance arts as soon as I could walk, and was then discovered by a TV crew in a mall at the age of 4. All my time spent in front of the camera eventually evolved into working behind the camera in film and animation, where I was far more comfortable and could finally focus on creating my own vision rather than being a part in someone else’s. Through my lifetime of work in moving images, I’ve always remained transfixed by working with still ones in the form of mixed media collage and decoupage. The transition from a career in film and animation to working on my analog creations and running my shop full-time was an organic one, spurred by the events of the last year. 2020 was a real year of reckoning and I decided I owed it to myself to focus on this art form that has been so important to me throughout my life, and hopefully showcase the beauty of recycled materials and paper arts to the wider artistic community.

Since childhood, collage has been a form of art therapy and a means to unwind, experiment and express myself. As a professional artist initially working in film and animation, it remained my favorite medium, but I always considered it a purely personal and private form of expression, which partially stemmed from the ways collage and paper arts are devalued and considered “lower” forms of art compared with traditionally high value mediums. For this reason, as well as the long Jewish history and influence behind paper arts, I made the decision to focus my artistic energy into collage-based and found materials creations, to both honor the history and beauty of the ancient practice of paper-cutting and to fully embrace the medium that sparks so much of my artistic passion.

Was Judaism always central to your artistic practice?

Absolutely. Even if it was in a totally subconscious way, I believe that just as we inherit intergenerational trauma, we also inherit intergenerational gifts and inclinations that rekindle our ancestors’ passions and creative spirit. I’ve really enjoyed learning more about the ancient ritual of Jewish paper-cutting because for me it represents an intergenerational link to my interest in recycling and transforming disposable materials.

I consider my work a form of artistic alchemy, and nothing feels more alchemical in nature to me than the history of the Jewish people. Through the shtetls, pogroms and countless generations of rebuilding life from scratch, our resiliency and ability to create new life from the unwanted and discarded is a central inspiration to my work. Just as our ancestors fulfilled hiddur mitzvah by cutting into scraps of paper, I want to encourage others to make the most of what we have by recycling and transforming materials that would otherwise end up in a landfill.

What role does Judaism play in your personal, non-artistic life?

I don’t think I have a non-artistic life, lol. One of the things I love most about being Jewish is that our culture feels like a generational artistic practice, that we each get to interpret and enact according to our own vision. I don’t practice the Judaism of my mother, nor she hers, but we’re all drawing from the same collective source and engaging with it in our own unique way. I’m probably the most bubbecore* person I know, so I love to cook and bake and go all out for the holidays, and create a space where there’s no “wrong” way to be Jewish and just celebrate life. I feel incredibly lucky to have been born into such a rich and beautiful culture. Exploring my own perfect balance of rituals and practices to incorporate into my life continues to be an ever-evolving journey.

*bubbecore: Like cottagecore for savta-spirited Jews who rock stylish mitpachot [hair coverings], hamsas and tracksuits, and are always baking and cooking up a storm for Shabbat and the High Holidays.

How do you define Judeofuturism?

For me, Judeofuturism is an aesthetic, cultural and political art form that combines millennia of Jewish history, symbolism and culture with futuristic and cosmological imagery to conjure a future wherein our traditions have continued to survive for millions of years and we are no longer plagued by oppression, destruction, displacement and historical erasure.

I’d always assumed the term Judeofuturism had long existed as its own established genre, so when I started using it to describe my work, I was shocked to find it had virtually no history of usage, or even a written definition. So what I had assumed was this long-standing collective term now seemed very personal.

But for me, the whole point of Judeofuturism is channeling the collective into the personal, and vice versa. So, while I have my own working definition of the genre, I’d love to see it used in its own unique ways by other Jewish artists and contemporaries, so that it can organically take shape and evolve as a truly collective Jewish art form. After all, Judeofuturism is about honoring the infinite bounds of Jewishness whilst imagining the Jewish future we wish to see.

You say that you often work from “found materials.” Where do you find them?

The accumulation of materials I work with are the product of a lifetime of scavenging, which began with my childhoods spent in the shuk [market] hunting for cheap and beautiful materials to make jewelry. Some items in my shop are over 100 years old and were passed down or gifted to me by family, survivors and elderly community members, and I’m still waiting for the right piece to use them in. I frequent estate sales, vintage markets and charity shops, and also take in damaged or surplus metals and glass to restore. My favorite means to harvest materials is definitely in nature; shells, sea glass, porcelain, gemstones, preserved plants and flowers are some of my favorite materials to work with.

I definitely see a lot of the natural world in your art. Is nature a major inspiration? What are other influences for you?

Nature and making use of natural materials is absolutely at the center of my art. I draw on cosmology and geology as main inspirations, and the moon is undoubtedly my favorite muse. Since Judeofuturism is about combining the past with the future, I like to imagine what Judaica would look like if it took on the aesthetics of each decade over the ages. As a result, some of my hamsas look like they would be at home next to Lisa Frank stationary in a typical ’90s kid’s bedroom, and I love that having so many inspirations and materials to draw from translates into so much aesthetic variation in my work.

What does the hamsa mean to you?

I grew up with hamsas and nazars prominently displayed at home, pinned on the inside of blankets and clothing as a means of protection, so the hamsa is something I naturally think of and use a lot in my work because for me it represents safety, protection and perseverance. What’s been really empowering in my personal and artistic journey is creating hamsas that I wanted growing up but that didn’t exist, like the Pride Hamsa I created to offer specific protection and blessings for LGBTQIA+ Jews like myself.

What relationship is there between your gender identity and your work?

I believe no matter what the subject matter of our work is, our experiences and identities are channeled into our art in some way or another. Some of my work, like my analog collage series, “Cowboys,” was created to reimagine traditional masculinity as a tender, queer and community-oriented experience. The amazing thing about collage is it’s an inherently revolutionary medium, in that it allows us to edit, remix or recreate our histories. For many artists who come from oppressed and marginalized communities, this is our chance to create the histories that should have been and draw attention to the people and stories that were revised and erased along the way.

In this context, I find that I’m drawn to exploring imagery and experiences that challenge and debunk prescribed constructs, and that necessarily means re-queering our history so that our stories are back in canon where they belong.

What do you like about the Instagram platform as a Jewish artist, and as an artist in general? What do you dislike?

I’m not sure I have many positive things to say about Instagram, but guess it wouldn’t be a Jewish interview without a hefty dose of kvetching! In theory, I like the idea of a platform designed to share artwork and photography, but I find Instagram quite lacking in even the basics of how it showcases and shares content. I know everyone has bemoaned the algorithm to death, but it seems particularly intent on silencing and shadow-banning marginalized creators, and severely limiting the audience to our work, which is the opposite of what the platform is supposed to do. When your own followers can’t see your posts, there’s no denying it’s a deeply flawed and counterintuitive platform. But we don’t have many other spaces to showcase our work as the internet as we know it has been broken up into a handful of social media platforms and forced artists to settle for how and where we show our work.

How does Judaism interact with all of your other identities?

I think I could spend a lifetime discussing this topic (and I absolutely have thus far). For one thing, I am a Mizrahi, Musta’arabi, and Ashkenazi Jew, so even my Jewishness contains multitudes that interact with each other in unique ways. Despite misconceptions that are held about us and sadly even perpetuated within our own communities, there are infinite experiences of Jewishness which means Jews from the same communities can have wildly different experiences regardless of intersections with other communities and identities.

Like many LGBTQIA+ Jews, I’ve found difficulty being accepted completely for who I am within my own community, which is why it has been so important for me to explore Judaism through a queer lens and find community with other Jews like me. On the other side, LGBTQIA+ spaces have become increasingly antisemitic in recent years and many Jews feel forced to choose between essential parts of ourselves, forcing us to suppress or hide one part of ourselves to find acceptance for another.

Jews like me, with complex identities that intersect with varying oppressed and suppressed identities, are facing a particularly difficult reality where there’s very few spaces where our full selves are welcomed and accepted. As a result, I seek to imagine, create, and hopefully foster space for all Jews to feel welcome and secure in their identity. I feel that my unique identity is a gift and I hope other Jews navigating and exploring their identities arrive at a similar conclusion, because it’s truly miraculous for us all to be here.