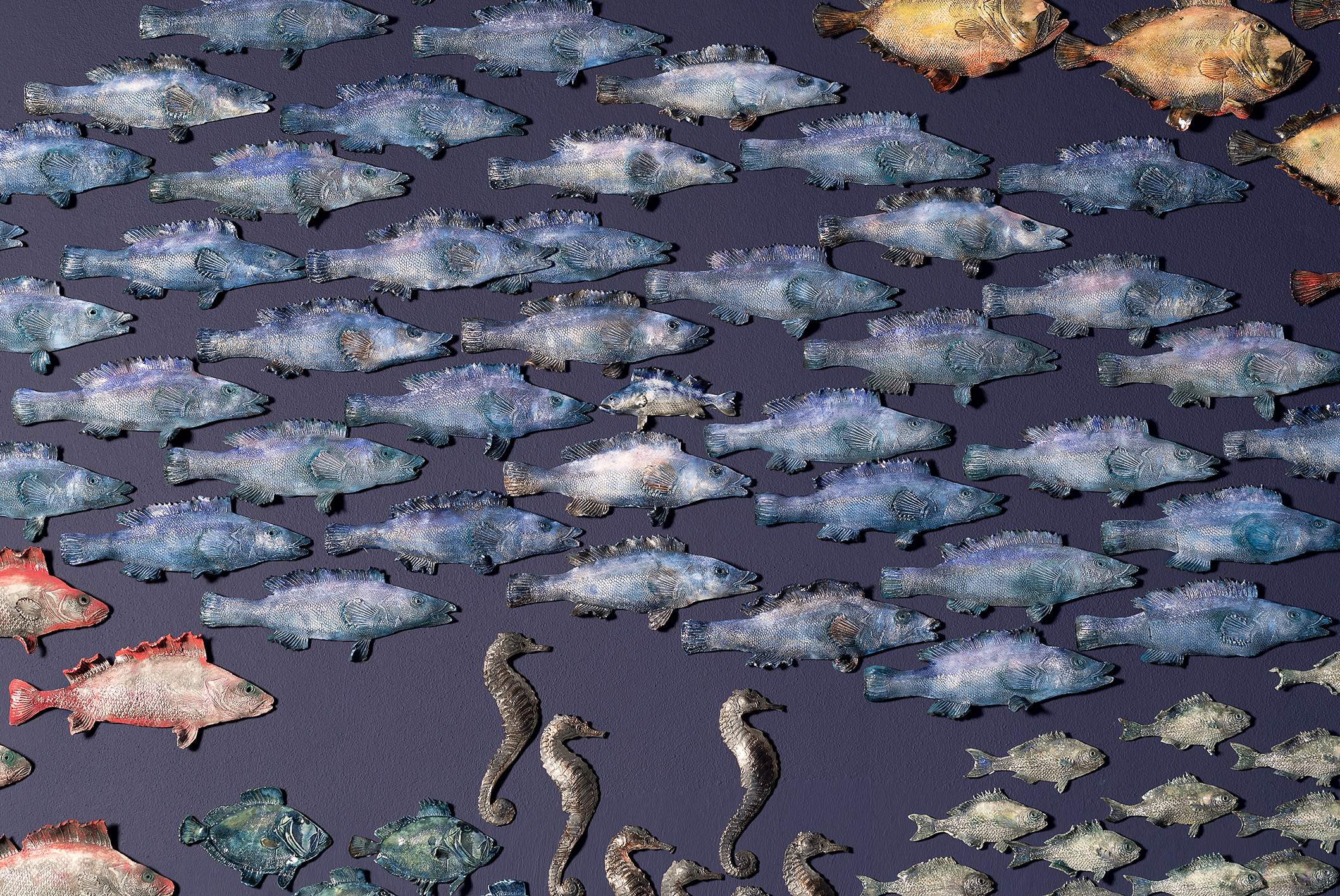

At the Gottesman National Aquarium in Jerusalem, a sea of colorful porcelain fish — 1,200 to be exact, each handmade and hand-painted — swims along a wall. Most of them stick with their own kind, grouped by color and shape. But if you look closely, you’ll see one little fish swimming the other way.

This piece, titled “I’m Not,” is the work of Israeli-American artist Andi Arnovitz, and it first appeared at the 2019 Jerusalem Biennale. Arnovitz grew up in Kansas City and moved to Israel in 1999. She has worked in a staggering variety of materials over her long career: In addition to ceramic, artists’ books (and paper in general) are perennial favorites, and she’s also constructed pieces from sticks and linen and film and silk. But some core themes, Judaism among them, run through the whole of her diverse output.

On the occasion of a new piece, a collaborative artist’s book launching at this year’s Jerusalem Biennale, I spoke to Arnovitz about how she articulates those themes, whether all art made by Jewish artists is Jewish, and why books are a great artistic medium.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

How (and when in your life) did you start making art?

I think I drew from the moment I could hold a pencil… I have some drawings I did as a child but I have very clear memories of everyone watching TV and me lying on the family room floor with a huge stack of cheap typing paper, drawing away. I remember my middle school art teacher in Kansas City, Elinor Eastwood, had a huge impact on me, as did my high school art teacher, Mr. Crawford. My mother was a docent at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City and I remember being taken to the museum very often as a child.

What was your relationship to Judaism like growing up? What is it like now?

This is a very nuanced and complicated question. My birth family was and are Reform Jews. I had no bat mitzvah, and did not have any kind of formal Jewish education. I did not know about Jewish holidays beyond Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Pesach. I did have mostly Jewish friends in high school, and I took a high school trip to Israel… it was something I took for granted, knowing I was Jewish, but it was not a particularly deep knowledge.

Later, after meeting my husband, I realized what I did not know. Which was a whole lot. He grew up affiliated with synagogues and day schools. He knew Hebrew. He knew the difference between Torah and Talmud. He likes to joke to that he snatched me out of the jaws of assimilation. Joining a shul and going often was part of our newlywed life. We had a kosher home. As we started having children (we have five) I began to understand the power of community — especially the power of a vibrant and observant community, as in, “it takes a village to raise a child.” Slowly, with friends, rabbis and visits to Israel, a Torah study group and lots of random people who had great influence, we became more and more observant.

Today we are Shabbat observant (and have been for the last 28 years). I honestly believe Shabbat saves families and marriages. Now more than ever. A day when you and the people you love disconnect from technology, from commerce, from a thousand distractions and you just are. You talk. You make eye contact. You make sentences instead of sending emojis. It is enriching, powerful and good, good medicine.

What drew you to Israel?

My husband was in high tech, working like a madman — his second company went public and we found ourselves in the crazy position of being able to do whatever we wanted. He said, let’s go to Israel for two years. The kids will become fluent in Hebrew, experience another culture and deepen their knowledge. He is a big picture guy. I, on the other hand, had an utterly warped and ridiculous idea that I would be sitting around painting lemon trees and sipping tea in little glass cups. It was very, very hard for me, not speaking or reading Hebrew. I stepped off that plane and literally lost myself for several years. I regret nothing now, it was character-building, but it was really hard at 40 with five little kids to do what we did. In the end, living here makes one part of the trajectory of Jewish life. You are part of the story, and this is an incredibly meaningful life here.

If there are themes across all of your work, what do you perceive them to be?

I believe there are definite themes: I deal with the places where religion, politics and gender meet. Sometimes just one or sometimes several. Living in Israel has brought these flashpoints into ultra-sharp focus. These are the subjects that interest me, that I feel are worth exploring. I deeply believe an image can sear itself in a person’s mind much faster and deeper than a long essay or lecture. My goal is to seduce the viewer visually, pull them in and then present them with an issue or problem — make them aware that something is broken, needs repair or needs to be recognized.

Do you feel that all of your work is, in some way, Jewish because you are Jewish?

Of course. My work is a total reflection of who I am. It is feminist because I am a woman. It is imbued with Jewish values because that is part of who I am. I am many things and it is undeniable that for all artists, this is part of what they create. You cannot really separate the core of the person from their creative output.

Why do you make books? What about that form appeals to you?

It really is such a futile endeavor because no one really collects artist’s books anymore except for institutions. The new generation of collectors is buying videos and NFTs, not an old-fashioned book form! But I love books. I love the intimacy of a book. It is private. It is not some splashy thing hung over your couch. It is an intimate, slow experience, a reveal that involves the viewer in a very active way. Artist’s books are not passive things you stand in front of. You turn the pages, you read, you experience. In some of my books you are required to open lids, turn things, examine things. I love when the viewer becomes active in the creative experience.

What materials do you generally like to work in? I know it varies across projects — how do you know what medium an idea should take shape in?

The idea comes first. Then I consider which is the best way to make that idea sing. Sometimes I realize it needs to be made out of something I know nothing about; a great deal of research then happens. In general, my happy medium is paper. I love paper. I sometimes call myself the “paper manipulator.” Whether it is a print, a book, a sculpture or a collage, I love playing with paper. I tend to encounter paper in a three-dimensional, not two-dimensional way.

Tell me about this new Jerusalem biennale project, “The House Is in the Book.” Who are your collaborators, what is the inspiration, how did you create the images that make up your pages?

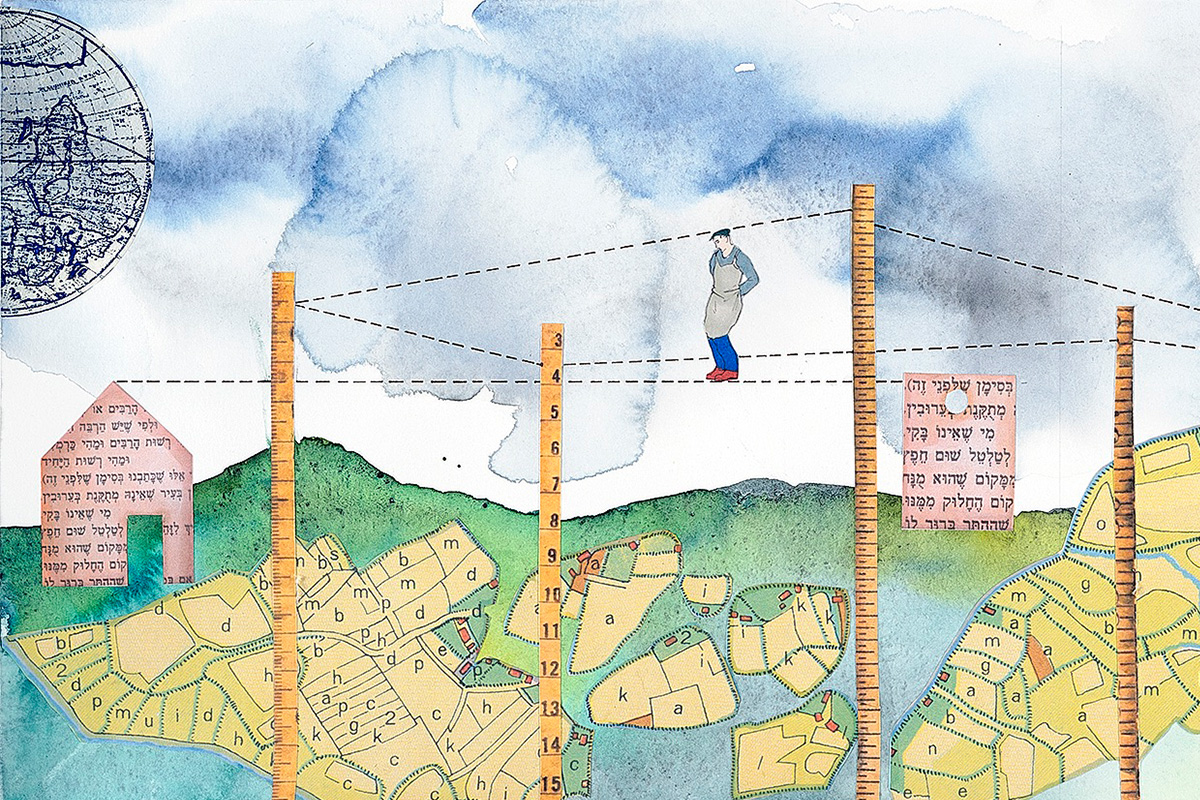

There are two brilliant artists I admire and adore and happen to now consider dear friends: Lynne Avadenka, from Detroit, and Mirta Kupferminc from Buenos Aires. About two years ago, just after the fourth Jerusalem Biennale finished, I knew I wanted to do something with artist’s books, and I knew I wanted to include both of them and the curator Emily Bilksi. The Biennale, directed and founded by Rami Ozeri, sent out a call with the theme of “four cubits,” a Talmudic term for a specific distance/measurement of personal space, which becomes super loaded and meaningful today with social distancing and isolation from COVID. We began to have regular Zoom meetings and we developed an archive of images that we each used and tapped into to create this shared, collaborative book. At one point we were zooming from Jerusalem, Glasgow, Detroit and Buenos Aires… We did an edition of 15 hand-assembled books and a video. The resulting work addresses collective experiences of loss and isolation, and explores re-conceived notions of private, civic and global space, refracted through the medium of books.

The entire experience has been over Zoom, with pieces of the final book created on three continents. My biggest nightmare has been getting Lynne and Mirta’s books here for the exhibition. They were not allowed into the country (hopefully they are coming in December for the closing) so we had to pay and have friends schlep their works to Israel in suitcases… The exhibition will feature this new collaborative book and video, plus many handmade artist’s books from each of us (the three artists).

Can you also share about “Nashkevillin”? I love how that piece engaged the community even at a distance. I think it’s a great model of successful art during COVID.

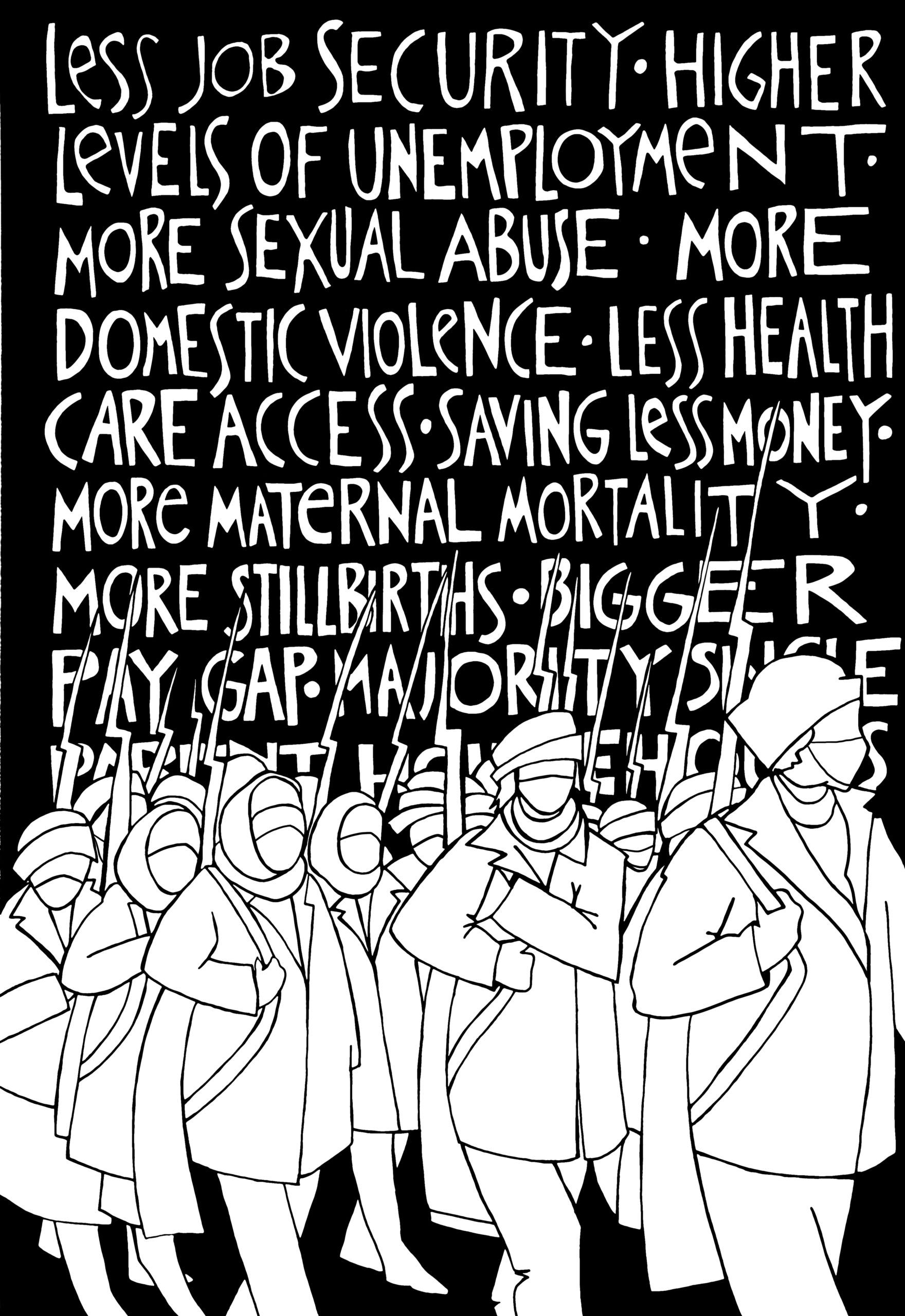

The 2021 Krakow Jewish Festival’s call was for proposals of works of art that could happen without the artists being there. This is a very tricky for artists. It involves a great deal of planning and also dependence on the producers on the ground. All this is hard for artists who are generally control freaks. Cornelia Renz, a fabulous feminist artist, fellow printmaker and friend from Berlin and I decided to co-curate and establish a sort of renegade group of feminist printmakers from three countries, Poland, Germany and Israel, who identify as women. Drawing on the historical precedent of Yiddish broadsides (large sheets of paper printed on one side) called “Pashkevillin,” we created a contemporary form, playing with the Hebrew word for woman, “Nashim.” We coined this new poster form, “Nashkevillin,” and tasked each artist with creating her own print/poster dealing with issues that they are obsessed with/committed to.

Many of the Polish artists are furious with the new right-wing government and the anti-abortion laws which have set women’s rights back decades — so they dealt with that. The German artists dealt with domestic violence, rape and eroticism. The Israeli artists also dealt with issues of physicality, the impact of COVID (my poster dealt specifically with this) and mixed identities which reflect the greater, complex Israeli national identity. These images were then sent to Krakow where they were cheaply printed. Part of the production team of the festival went out at night and plastered the posters on walls and kiosks and buildings in Kazimierz, the Jewish quarter where the festival took place. Of course the posters outraged some people, and many were defaced, torn and painted over, but many stayed and they created a statement.

Today in Jerusalem the project has taken on another life, as I am giving workshops for people who want to come in and make their own feminist poster. Hamiffal is a buzzing creative hub in the heart of Jerusalem and also a co-producer of the Krakow Jewish Festival. They brought the four Israeli artists who were part of this last festival together to do shared workshops based on our projects. It has been very interesting to transfer our festival projects to another city.

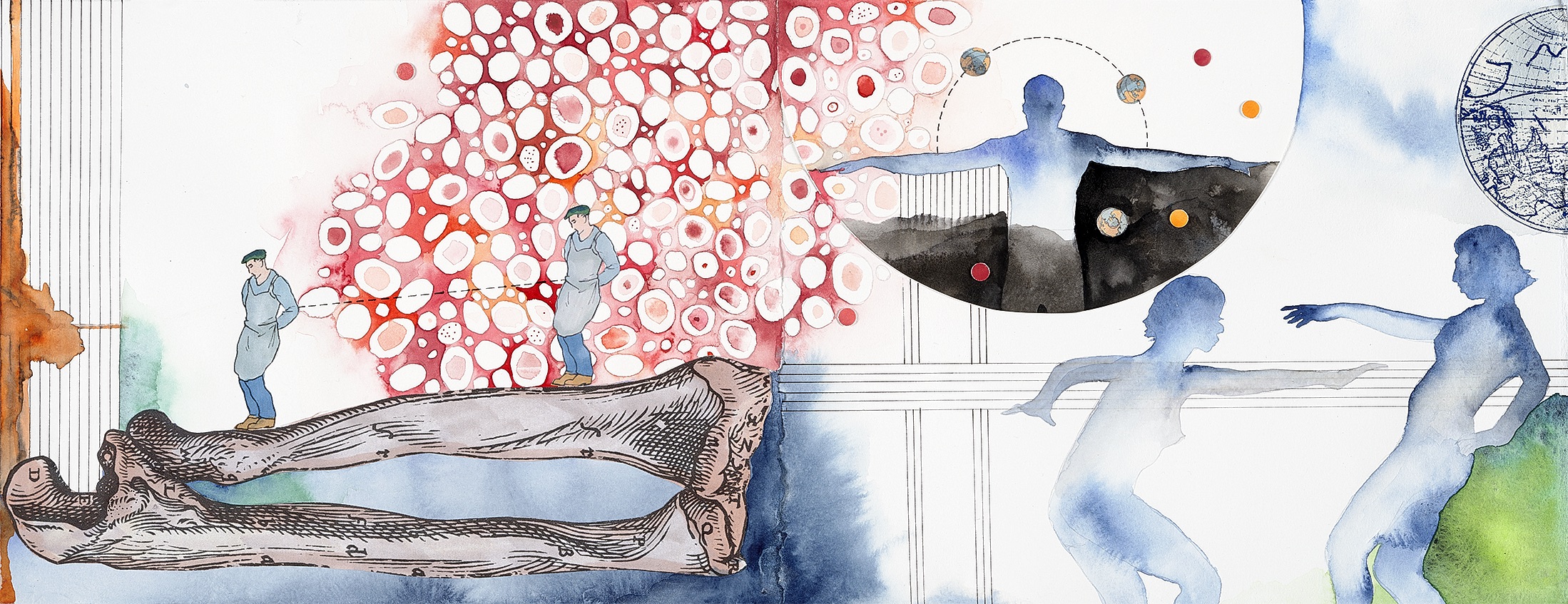

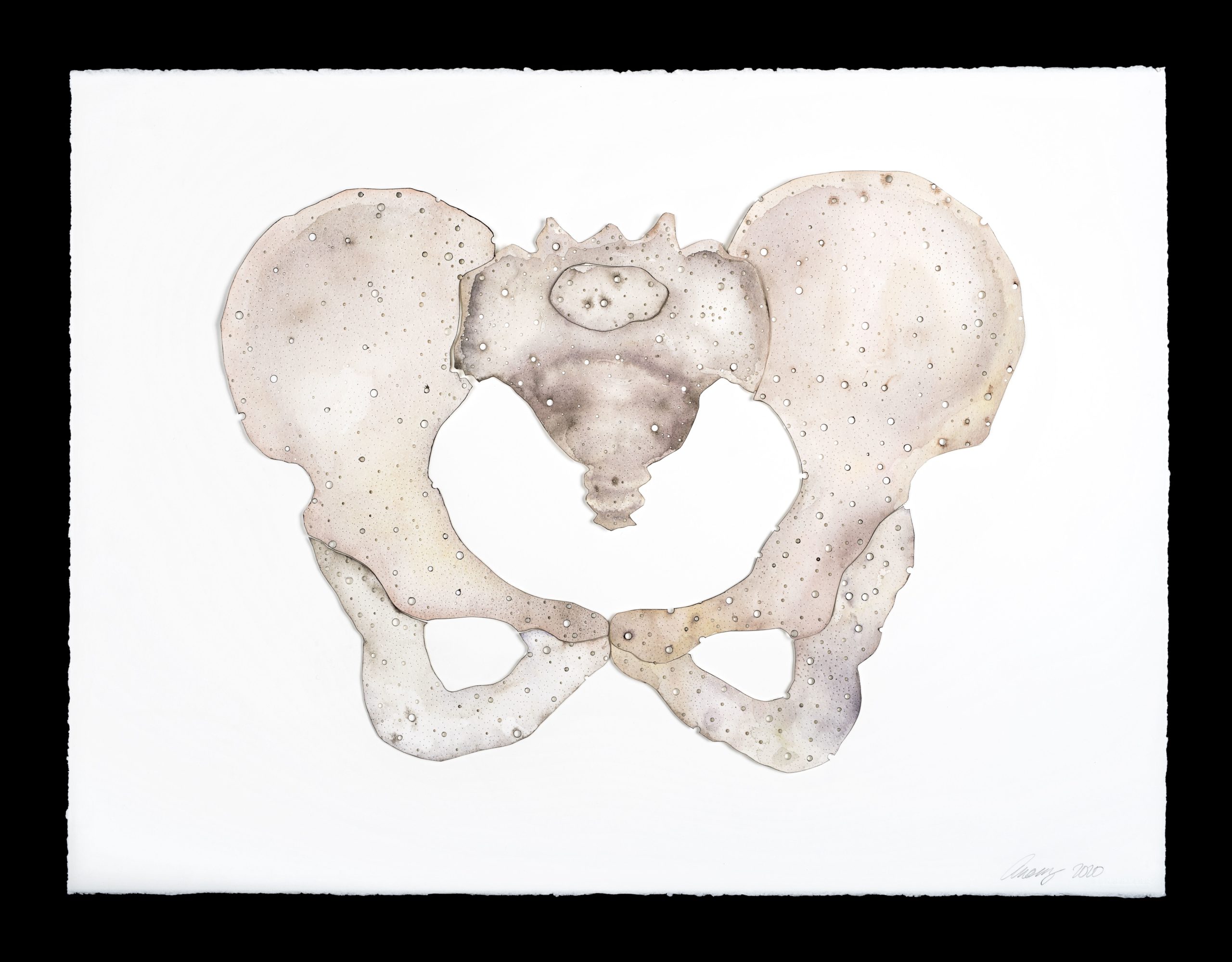

I found “Osteoporosis” completely mesmerizing. Did a personal experience spark that project, or something else? How are you exploring aging in that and other work? It came out in a year when disease and vulnerability, and the susceptibility of the elderly, were very much on the public’s mind.

I was diagnosed with osteoporosis several years ago and I take medication for it. It’s very common in women my age. What fascinated me, and continues to haunt me, and was driven home even more by COVID, is how things happen in our bodies which we cannot see. Someone I love very much is battling cancer and the whole way it suddenly manifested itself, and how long it had been lurking, hidden in her body — these are things that I am obsessed about. I did a lot of work one could deem “medically themed” the last few years. The pieces started well before COVID, but the onset of the pandemic just made the exploration more relevant. When you look at cancer cells, a COVID virus spore, at a bone riddled with osteoporosis up close, they are magnificent — which is the other weird and strange side to this. There can be a kind of visual beauty in horrible things.

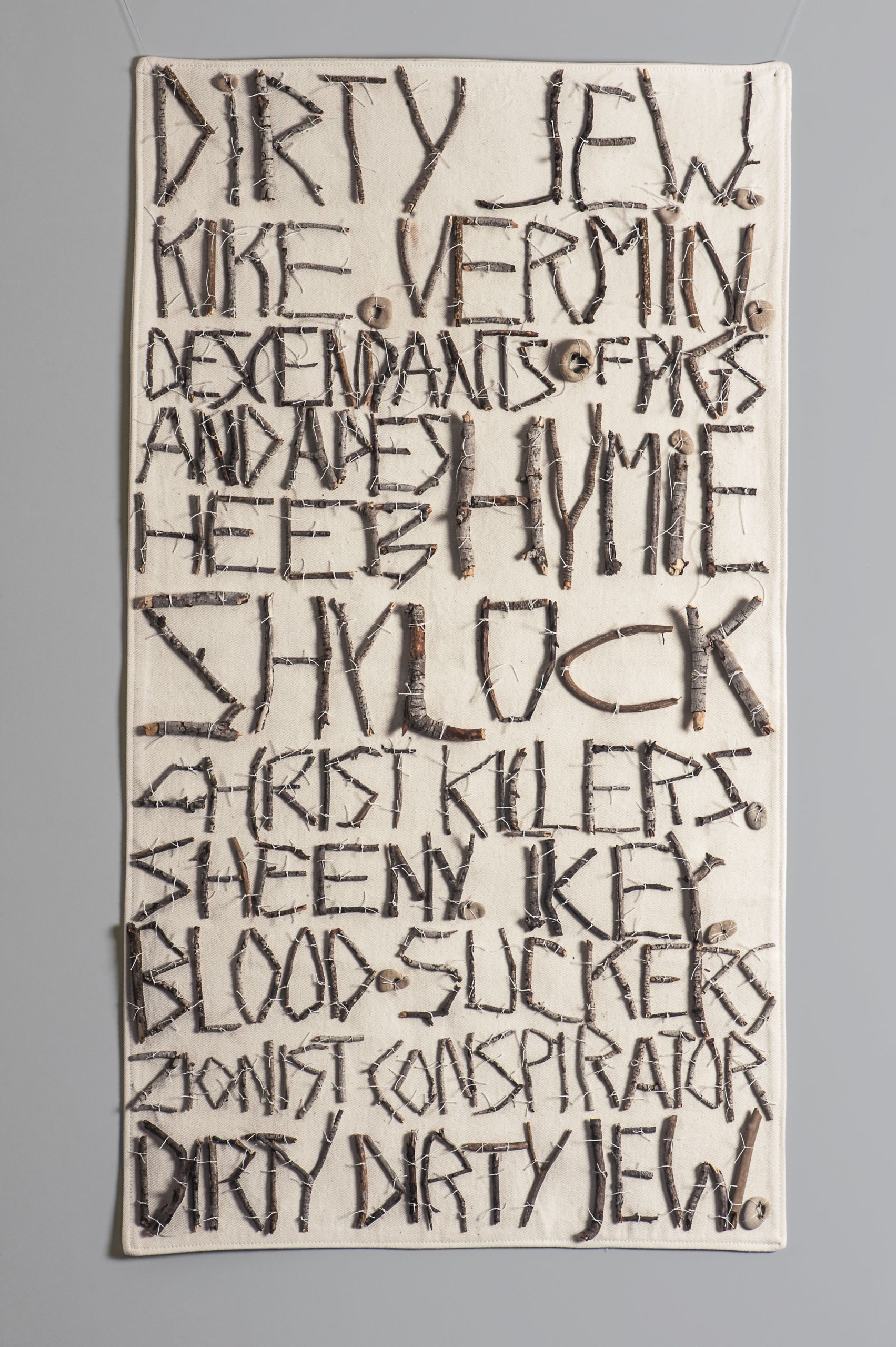

Did any specific event plant the seed for “Names Do Hurt Me”? What was the response to it like when it came out in 2018?

Antisemitism is as old as the world, but now it seems to have become more socially acceptable to say awful things, to spread lies and conspiracy theories about Jews, especially Israelis. I still have a very difficult time with getting my head around this new trend in which facts and recorded history no longer matter but what someone’s truths are is the only thing which carries weight. It seems individuals are not interested in learning or engaging or listening, but in shutting down and shutting off. I believe there can be alternate narratives and parallel histories, and I think that is a huge thing we have to reconcile. But erasing and canceling doesn’t portend very well for our futures, or for productive dialogue. This piece was created in light of this blooming ugly antisemitism, and in response to violent acts of terror both in the USA and Europe. I took my cue from the childhood rhyme and played with sticks and stones and sewed the piece with every evil name for Jews I could find. It was very cathartic. It has not actually been in any formal exhibition, but is on the online curated exhibition “The Consequences of Hate Speech” by the Vector Artists Initiative.

Jewish artists who inspire you?

William Kentridge. My idol. Consummate printmaker and draftsman. Deep thinker and conceptual artist. I am green with envy. Judy Chicago. Helene Ayalon. Michael Rovner. Sigalit Landau. Maya Zack.

Other sources of inspiration?

I look at a lot of coffee table books; I call them eye candy books. I get ideas in strange ways, and usually not from looking at other artists’ work, but from travel images, interior spaces… I listen to a lot of music and podcasts while working in the studio. I daydream and this is a very important part of my artistic practice.

Any advice for Jewish artists who are looking to have a successful and varied career in the Jewish art world, as you do?

Obviously talent is needed. Unique media and ways of working are critical. I would say be careful and stay away from trite and kitsch — if you are going to do a piece celebrating Shabbat, you’d better be sure it is unique and revolutionary because otherwise it is going to be unremarkable. I think Judaism as a starting point is worth exploring over and over again. There are new issues and new ways of looking at things. At the same time there is a lot that is broken and needs repairing and that voice, too, is perfectly legitimate.

I think regardless of what you do, it is important to find your voice and way of working. There is an authenticity to work that is made from being inside something — from being part of it, close to it. That is not to say one cannot feel empathy for or explore something foreign, and sometimes bringing fresh eyes and perspective to something can be brilliant. There is an insidious thing happening right now in the world of culture, which is the claim that one is not allowed to explore anything that doesn’t belong to you. There is something fascist about this way of thinking. The world will be so much poorer if artists, writers, musicians and other creatives can only work on what they can document as being theirs. Empathy is a unique human trait. To censor this is a crime.

Is there an image from Judaism you find particularly striking or meaningful?

I would say that when I am out in the Israeli desert, in the Judean hills outside of Jerusalem on the way to the Dead Sea, I am overwhelmed with the vastness of the desert and the sense that the Jews needed the idea of God to root them and to create a sense of meaning… The image of the Jews wandering in the desert, and the need to put down roots and stay put, and then create an entire system for living — for civilization, for me, it is compelling.

Andi Arnovitz’s work is currently on exhibition at Hebrew University’s Stern Gallery; the Jewish Museum in Augsburg, Germany; the HUC Gallery in NYC; the HaMiffal Gallery in Jerusalem; and the Jerusalem Print Workshop as part of the Jerusalem Biennale.