When I was a kid, I knew exactly what I would do if Nazis came to my house in the middle of the night to take me away.

The plan? Escape, ask a friend to hide me, and join an underground resistance. I would lay awake at night agonizing over which family I would ask to hide me, confronted with a zero-sum game: that I must put someone’s life in danger in order to save mine.

It sounds crazy, but it never occurred to me that it wasn’t normal to daydream about your own survival. To me, a Jewish kid who had been learning about the Holocaust since fifth grade, Nazis were as plausible as a hurricane — something that had happened and would happen again; a natural cause.

I had been confronted with Jewish genocide from such a young age I got anxious at just the mention of the Holocaust, nauseous from a fear that was inside me, but not necessarily mine.

I thought I was disgusted with humanity.

It wasn’t until I learned about epigenetics, a scientific study of DNA, that I realized my anxiety was legitimate. Epigenetics shows that trauma from our ancestors can get passed down to us through our DNA. It is more commonly referred to as intergenerational trauma.

This anxiety has been mounting since President Trump was elected in 2016, yet America has also been in a clear divide over the significance of his threat to our democracy since that day. Those of us who were called alarmists, me included, were told to stop overreacting, that America was different, that everything would be okay because we had a stronger democratic society than other countries.

Well, even if that was true, everything is no longer fine.

In the first presidential debate, when asked to explicitly denounce white supremacy, Trump told the Proud Boys, a white nationalist group, that they should “stand back and stand by.” At his town hall on October 15, Trump denounced white supremacy but refused to do the same for QAnon, a pro-Trump conspiracy theory that peddles in classic antisemitic tropes. The ADL has reported a spike in antisemitic incidents and hate crimes — including deadly attacks on synagogues — since 2016

America is on the brink of something, and of course, it’s not just Jews who are afraid.

It is not 1939, and yet the police are still slaughtering unarmed Black men and women in the name of “justice,” still separating refugee families at the border and putting their children in cages, still performing medical experiments on female-bodied prisoners.

Sound familiar?

My recurring nightmare of Nazis breaking into my house and capturing me is becoming more tangible, but now it’s informed and comprehensive and absolutely terrifying. And while I’m a fan of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds, I don’t think I’ll be knocking Nazi skulls anytime soon. I’m more prepared to find myself in a police-state wherein me and my loved one’s basic liberties will be stripped and some of our lives taken, along with members of every other oppressed group in America.

I am not going to back down from this fight, mainly because I have nowhere else to go — as a descendant of Ukrainian Jews, my ancestor’s recent homeland does not exist anymore. But I am not the only one weighing my future and analyzing my family history. Many Jewish people are choosing between becoming refugees or staying and doing what they can to fight.

Molly Safar, 27, said she isn’t going anywhere.

Safar, who currently lives in New York City, said that she feels an obligation to stay and use her privilege to fight. Already an activist in many spaces, she feels that this is a moment for action.

“We’re living in a moment of history and people are still wondering what they would do,” she said. “The Holocaust isn’t happening now, but the neo-Nazis think it is.”

She said that she thinks the most important thing right now is to work out differences between marginalized groups, to get everyone on the same page about who the enemy really is.

“The Nazis are ready. Trump’s intentions don’t matter, because if he leaves, the Proud Boys are ready to move on.”

Rebecca Brier, 37, who asked to use an alias, feels differently. She and her husband are in the process of getting Portuguese citizenship for themselves and their two young children.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned from my family, it’s that it’s okay to be the first one to go,” she said. “It’s harder with kids. We speak Spanish, but Spanish is not Portuguese.”

Brier said she is mainly torn between leaving her family behind in the Bronx or figuring out how to get them all to Portugal.

“We’ve set up our lives around our support system, our family. If we left, would we be that anchor again? At some point, flight becomes easier, because if I fly, at least I still have my family.”

But not everyone has the luxury of leaving.

Aviva Davis, 21, is a biracial Jew whose ancestry is more closely linked to slavery than the Holocaust. They feel it is a luxury that white Jews are able to consider leaving at all.

“I would love to have an escape plan, but it’s not a viable option for me,” they said. “Where would I go? My ancestors were carted over here as slaves — white Jews can trace citizenship back to their ancestors. It’s very frustrating for me to feel like I have nowhere to go.”

Davis, who currently lives in Boston, also has dreams of pursuing a career in the States: getting their masters and PhD is an important part of their life plan and leaving would make that goal much harder. They couldn’t see themselves leaving the country.

“It’s part of my job to fix the world. If I leave, who’s there to advocate for us?” they said.

If those of us who are able to flee do leave, we risk taking away a line of defense for the people who will be persecuted first. But if we stay and fight, we risk shrinking our community to the point it may never recover.

It is a dilemma with no black and white answer.

As Brier said, “Do we become Jews lighting candles in the closet in Spain? Or do we flee to the Ottoman Empire? I’m not sure who did it right. But the trauma is still there.”

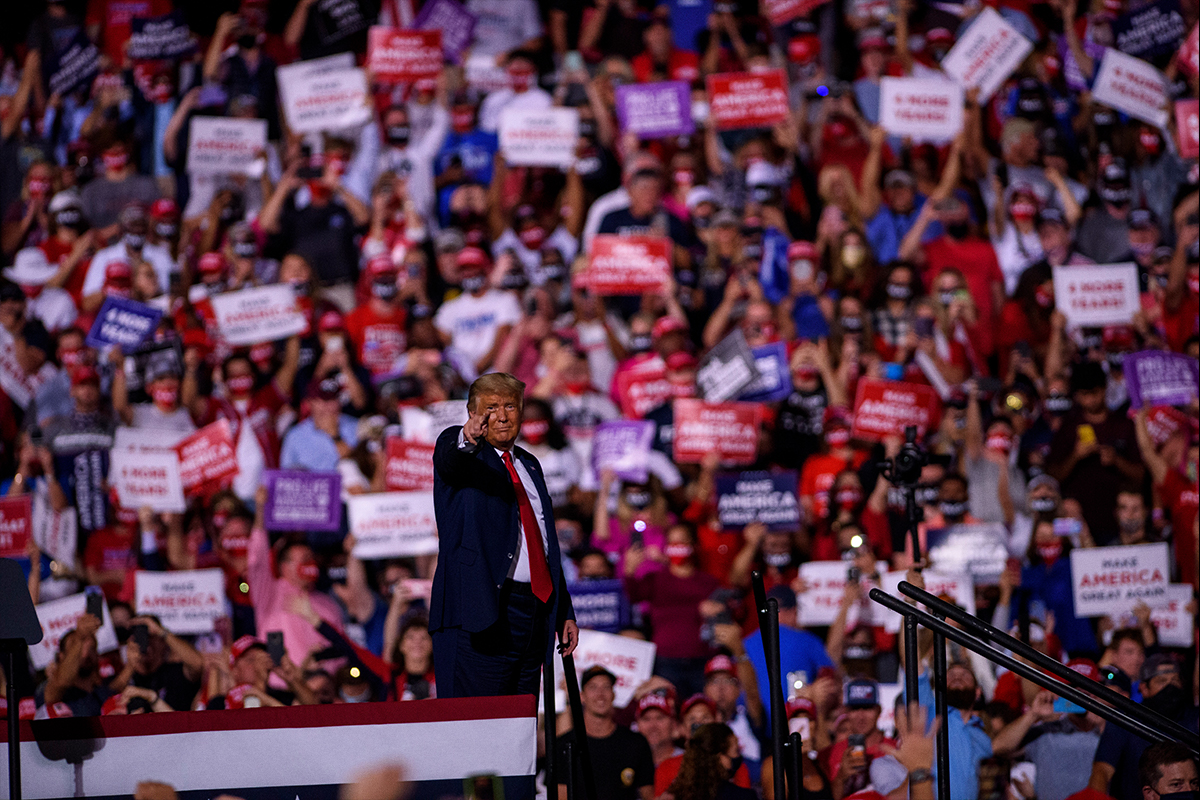

Header photo by Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images.