“You jews should not complain.”

“What?” I stared at my coworker, trying not to let my building anger seep into my eyebrows. We had been having a conversation about the rise of racism and anti-Semitism during this Trump era, and she was now informing me that Jewish people didn’t have a stake in the matter. I’d always felt safe with this coworker, but in that moment I found myself questioning if I should have ever shared the fact that I was Jewish with her.

“Jews are more privileged than white people! I mean, look at the entertainment industry—all Jews! I just went to a Jewish wedding last weekend. The education in that room was collectively higher than this entire neighborhood!”

Jews, like all diasporic peoples, hold a fluid identity marker in society. While our physical features have been used to present us as “other,” they have also been used to loop us into the majority. It’s an interesting place to be: Try to call out anti-Semitism and you are met with, “But you’re white!” Try to blend in and someone who you thought was a friend informs you that, “You have such a Jewish nose” or drops an incredibly offensive Holocaust joke.

I went to Jewish Day School growing up, and while I’d like to think my experience was similar to friends attending different religious schools, I wonder: Did they also receive monthly bomb-threats at their school? Did they also have their school graffitied with the words “Jesus killer”? Did they also have men with swastika tattoos stand on the corner signing the heil Hitler? Did they also go to the Museum of Tolerance and search for the names of their relatives on the walls commemorating 6 million murdered Jews?

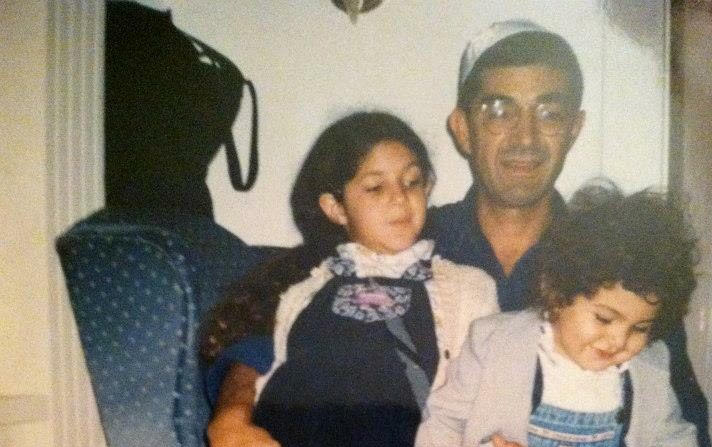

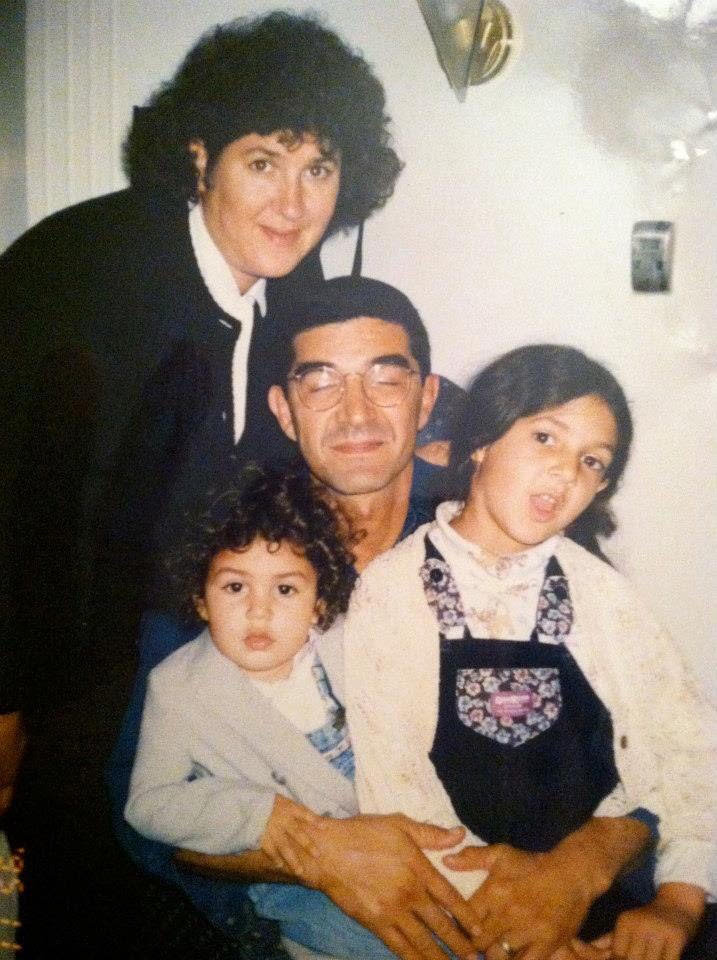

While my mother is Jewish, her grandparents from Germany, my father is Mexican, his ancestors from Chiapas and Basque Country in Spain. I’ve gotten to experience the cultural joys of both Passover and Día de los Muertos, challah and birria.

My bicultural background has given me a passport into both of these worlds. My bicultural background has given me a rich identity. My bicultural background also made me realize the fickleness of identity, as a marker of who you actually are and as a source of division and tension where there could be unity.

When I try to explain to people that I’m half Jewish and half Mexican, people often tell me that you can’t be half-Jewish because you can’t be half a religion. When I tell people that I’m Mexican, people often say things like, “But you’re not that Mexican, right?” or, “You’re like a white Mexican.” These kind of comments have made it tempting for me to completely reject the notion of identity altogether. However, the pride I have for my background is greater than the frustration I have around explaining it to people. My optimism that people will get to a place where they can approach identity with curiosity is greater than the pain I’ve felt from their judgement.

I imagine that many people, every day, are told what they are and what they aren’t. The problem with labeling someone’s identity is that by doing so, you inherently deny the person the ability to create their own complex, evolving identity. This morning, I wanted to start running. This afternoon, my focus centered on perfecting the art of handmade pasta. Am I health nut or a glutton for carbs? You guessed it: I’m somewhere in between.

The other problem is that our understanding of other people’s identities will always be limited, unless we allow them to fill in the blanks and share their perspective. I am culturally and ethnically Jewish, though I am not very religious, which many people don’t understand because their limited experience with Judaism leaves them ripe with images of menorahs and dreidels and lacking in historical breadth around the ethnic nature of the religion. I am Mexican, and when people seem shocked by that, they are presumably implying that my education and career trajectory are at odds with the Mexican stereotype they have in their heads.

Being bicultural has allowed me to see that certain traits of identity are simultaneously meaningful and meaningless. I can wear an embroidered shirt, put in hoops, speak Spanish, bargain for chanclas, and walk through Tijuana without anyone batting an eyelash. I can put on my knee-length skirt and recite Aleinu in synagogue and expect five grandmothers to offer to set me up with their single grandson. The fact that my Jewish grandmother made matzah ball soup that was so good it probably held supernatural abilities to cure the gravest of ailments does tell a part of my story, but it wasn’t the reason I chose to be a teacher. The fact that my Mexican family used to crack jokes and roast each other so strategically that they could simultaneously call out a family member’s deepest insecurities while making them feel like the most loved person in the world might account for my love of comedy, but it does not explain my love of dogs.

However, when I tell people that I’m Jewish or Mexican, they make an immediate assumption that because they know these two markers of my identity, they understand who I am as a person.

When you come from two cultures, what you realize is that it would be impossible to be defined by your background, because you have two; it’s like a double negative. How can I define myself as Jewish, when I’m also Mexican? It leaves me feeling like I’m technically neither. I can never fit perfectly into one identity, but I can pass as either (if nobody’s looking closely.) Being from two cultures has had a huge impact on me, and also, it’s shown me that I can’t possibly be limited by that part of my identity alone.

In an era when our president labels people by their identity in a way that’s incorrect at best, and racist at worst, we have to understand the simultaneous importance and utter irrelevance of identity. Whether you’re talking to your coworker, your friends, or random internet trolls, it is equally important to explain that any privilege Jews have cannot erase the litany of oppression we have faced as it is to explain that we need to rally our privilege and use it to continually help those without. It is equally important to explain that Mexicans are not rapists who crossed the border illegally as it is to explain that that not all Mexicans want to immigrate to the United States. It is equally important to explain that some white women have a one-dimensional view of feminism that doesn’t include women of color and trans women as it is to explain that many white women are doing incredible work to raise awareness around intersectionality. It is equally important to stress the idea of “staying woke” as it is to explain that “being woke” is not a badge to be earned but a call to continually deepen your understanding of the dynamic systems and cultures around us.

And most of all, it’s equally important to explain that we can seek to understand people’s identities as it is to explain that we can never fully understand people’s identities, and that’s OK.