It was a late winter Friday afternoon in Lower Manhattan. Exiting the Grand Street subway station, I made my way through the north edge of Chinatown where fresh fruit mongers and gift shops still adorned with red and gold streamers and paper dragons from Lunar New Year. Not five minutes later I was on the Lower East Side and had passed by both the Tenement Museum and Russ & Daughters cafe, icons of New York City’s Jewish immigrant story. If I kept going north I would hit the historically queer East Village, but I redirected west on Orchard Street.

I live in New York, I know these places exist and their proximity to one another. But in this particular moment, I couldn’t believe how well-suited the locale was for my destination. It was a true moment of bashert. I had converged on this queer, Jewish and Chinese urban landscape, which in turn converge on one another, because I was on my way to the Hannah Traore Gallery. I was going to see Chella Man’s debut solo show.

Chella is a 25-year-old Deaf, trans, Chinese and Jewish artist, actor and, in his own words, cyborg (he has cochlear implants). He first came into the public eye in 2017 when he created his YouTube channel and started going viral for videos which centered on his identity and personal life. Since then, he’s signed with IMG models, played Jericho in the DC Universe’s digital show “Titans” and written a book. But a through line for his creative pursuits has always been his art and his Deaf, trans, Chinese and Jewish identity. Now, his exhibition speaks to the all these intertwined facets of himself. Aptly, the show is called, “It Doesn’t Have to Make Sense.”

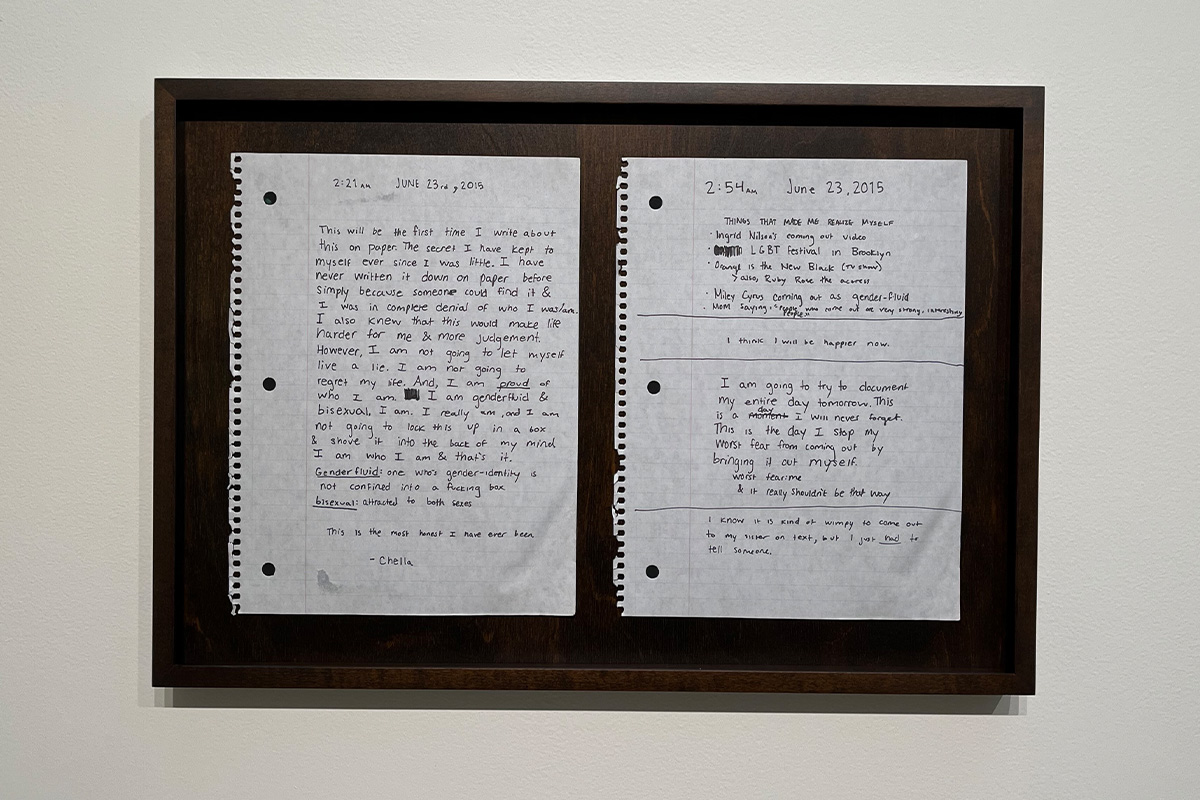

Inside the main room of the gallery, the walls are filled with pages pulled directly from Chella’s sketchbooks and diaries, going all the way back to 2014, as well as some paintings. One entry titled “2:21 am June 23rd, 2015” documents the moment a teenage Chella claimed his gender identity and sexual identity. “I feel as if it is not top surgery I am recovering from it’s spending years. My entire life in a body I do not connect with,” Chella declares in another diary entry on the wall. Another simply says, “How do you picture God? Answer: She is a Gay Black Queen.”

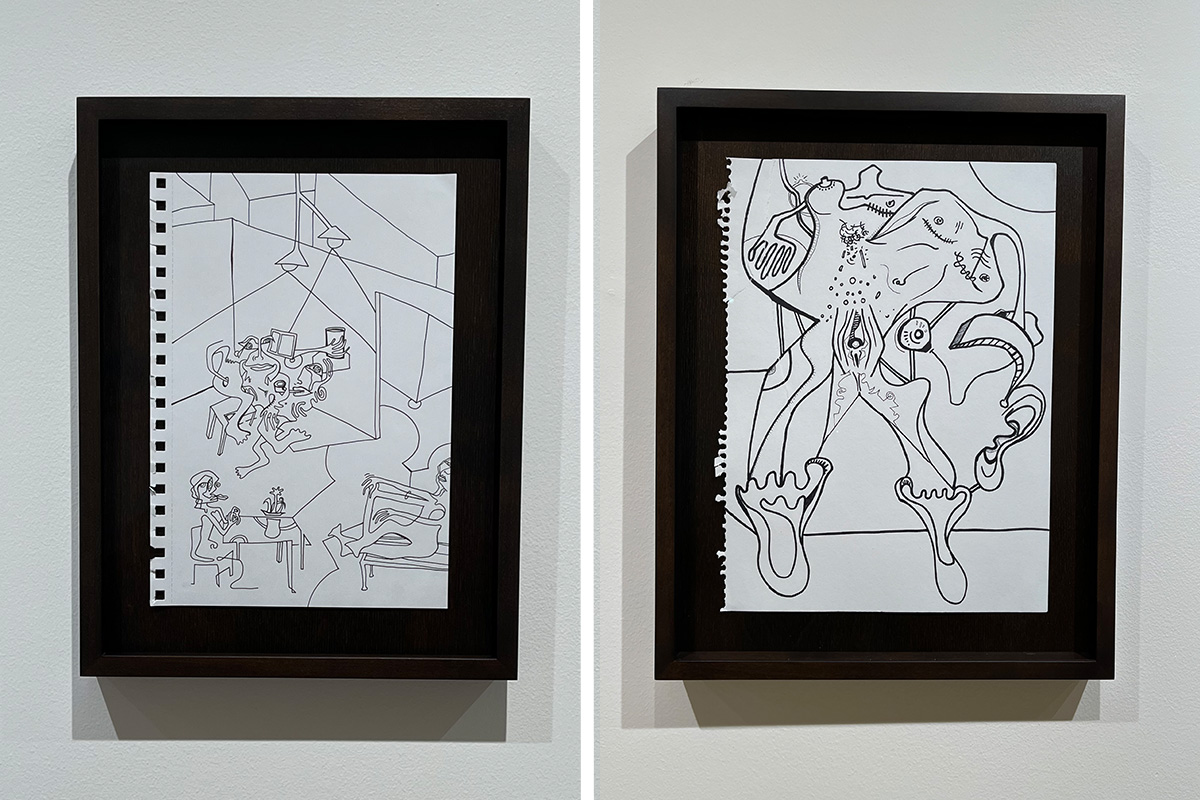

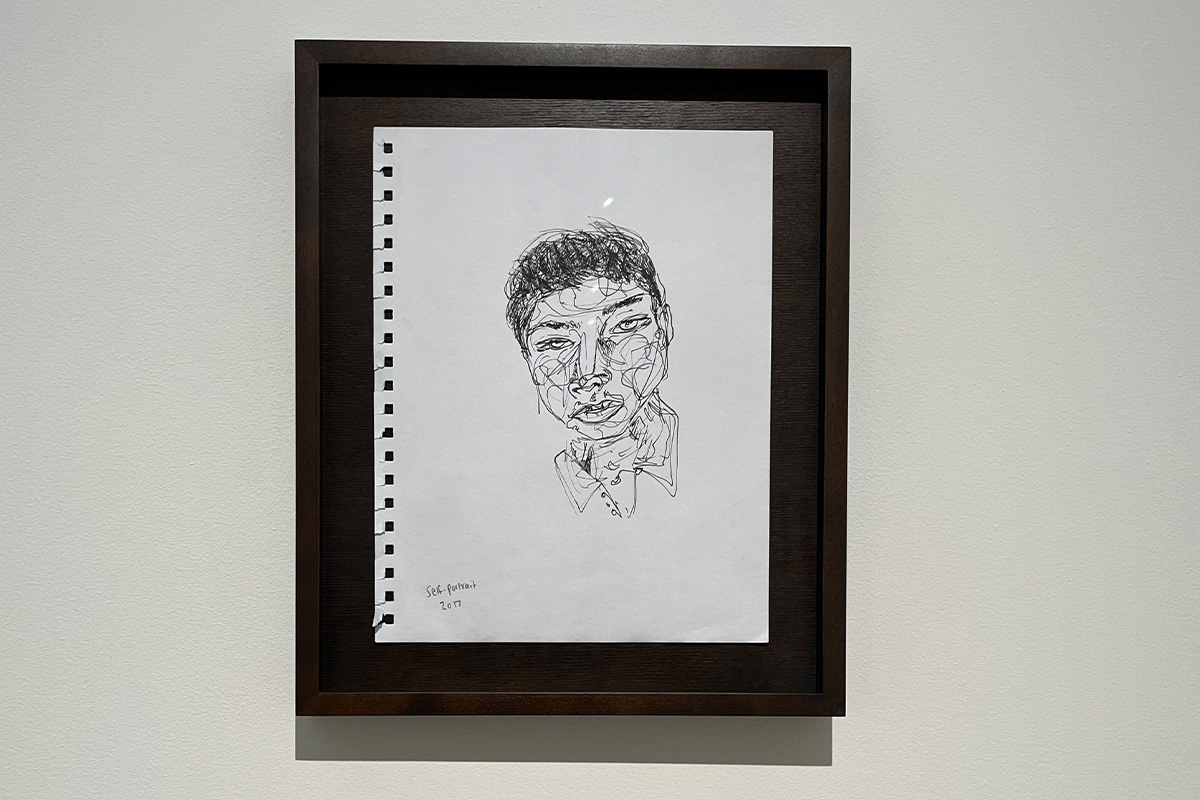

The sketches themselves focus on the ideas of disembodiment and being ungrounded in physical space. Figures with not fully-formed bodies (at least by able-bodied standards) flail in space; necks which turn into ears and cochlear implants, singular breasts on torsos with chest hair and top surgery scars, ever-opening vaginas, mechanical-looking penises, unidentifiable other forms of genitalia, faces without heads, three-fingered hands and more twist and turn devoid of a sense of place. Though Chella tells me he doesn’t often find inspiration in historical references for his art, to me, his drawings hold resonances of Russian avant-garde artist Pavel Filonov and Ashkenazi Jewish painter Marc Chagall. At the same time, the entirely black ink strokes of the works — heightened by the gallery’s entirely white walls and decor — call to mind Chinese calligraphy, something that Chella’s paternal grandfather was skilled in and known for in Hong Kong and Canada.

“None of this has ever been seen side by side,” Chella told me of the collection. “To put [my sketches and diary entries] on a wall to be seen alongside each other was remarkable because I was able to make connections visually that I was never able to do before now. I am just realizing and uncovering a lot about the story of my life that I wouldn’t have been able to unless I took the time to really organize and reflect in this visual way.”

He’s also quick to credit gallery owner, fellow artist and fellow Jew of color Hannah Traore for her guidance in realizing and bringing lucidity to the show.

“It Doesn’t Have to Make Sense” is clearly only the beginning for Chella. He’s currently working on a show with the Jewish Museum — a live performance called “Autonomy.” Though Chella didn’t share what the performance itself would look like, the center of the piece seems to be exploring his own body as a canvas, and the liberation and revelation he finds in piercing his own skin through tattoos and surgeries. It’s a work that specifically celebrates queer, disabled and trans bodies. By presenting this work through the Jewish Museum, I think it will also push back on the stigmas against tattooing and queer expressions of gender that are still held in some Jewish communities.

“‘Autonomy’ is really this piece that intertwines somatic healing, understanding and revelations I’ve made throughout my life in the form of different tattoos that I’ve designed over the course of 10 years. And also just revealing and exploring how the medical industrial complex has impacted me as a disabled person and as a trans person and as a Jewish and Chinese person,” Chella explained. “It really can only be done in this way right now because I’m at this point in my life where I feel the most somatically free and I have such a deep understanding of different systemic hurdles that I’ve experienced throughout my life growing up. Also beyond that, I’m connected to my body physically, more than ever before because of my gender-affirming care and I’m older and I understand myself as a person.”

For all the questioning of his identity he’s faced through the medical industrial complex as well as just generally as a Deaf, trans, Chinese and Jewish person, Chella shared that he’s felt very lucky in Jewish spaces. As a child, Chella attended synagogue where he met an important person who was one of the few openly gay people in his central Pennsylvania hometown: his rabbi. This experience lead him to feel welcome in his Jewish community, and he never had to wonder whether he would be accepted by the religion he grew up with. “And since moving to New York, and meeting so many other queer or disabled Jewish people, it’s been such a blessing to never feel out of place in those spaces,” he said. “It’s always made me disappointed and heartbroken when I do meet other queer, disabled, Jewish BIPOC people who have felt exiled in these spaces.”

Nowadays, Chella identifies with Judaism in the ethnic sense, not the religious one. Still, he finds meaning in the Jewish piece of his expansive identity. “My Jewish heritage is so intrinsically tied and connected to my mom’s side. Whenever I think about being Jewish I really do just think about the femmes in my family: my mom, my bubbe and my experience practicing and celebrating different holidays and exploring different traditions with them,” Chella said. “Being Jewish has also taught me, of course, that the underdog can win.”

“It Doesn’t Have to Make Sense” is at the Hannah Traore Gallery through March 30, 2024. “Autonomy” will be performed on May 2 at 7pm ET at Performance Space New York.