Disobedience is the tale of forbidden love between Ronit and Esti, two British Orthodox Jewish women. Based on the 2006 eponymous novel by Naomi Alderman, it’s a remarkable film released on April 27.

Rachel Weisz, who stars as Ronit and produced the film, explains, “Transforming the book into its own new entity was an incredible journey. As a Chilean, the way in which Sebastián [Lelio, the director] sees the world is very different from how a British filmmaker might see it. He had to immerse himself in this society and investigate it like a cultural anthropologist.” This lens — that of a Chilean, non-Jewish filmmaker — makes the love story of Disobedience the movie very different from Alderman’s book. Lelio is on the outside looking in, rather than Alderman’s insider knowledge of the community.

In the inspiration to transform the book into a movie, Weisz explains, “There’s almost nothing taboo anymore, so the term disobedience means very little unless you can find just the right place to set it in, like the small Orthodox Jewish community. If you find a story of transgression within an ordered society, you have a great universal drama that anyone can relate to.” This frustrated me, as if they were just trying to tell a story of forbidden love and happened to set it in the Orthodox Jewish community, because Alderman’s Disobedience is fundamentally a story of the Orthodox Jewish community.

Weisz’s producing partner, Frida Torresblanco, echoes her: “It’s about beautiful human beings trying their best under very difficult circumstances.” The film does become a great universal drama, and yes, it is about beautiful human beings, but it really wobbles in understanding the very Jewish aspect of it all. As Lelio, the writer/director explains, “Although the Jewish Orthodox background is very important, what’s really going on in the film transcends cultural specificity. At the heart of Disobedience is something very universal.” In his eyes, this is a “universal” queer love story first, and a Jewish story second.

I’m here to say: There are some things that simply cannot become universal. And that’s okay.

Ronit as the Center

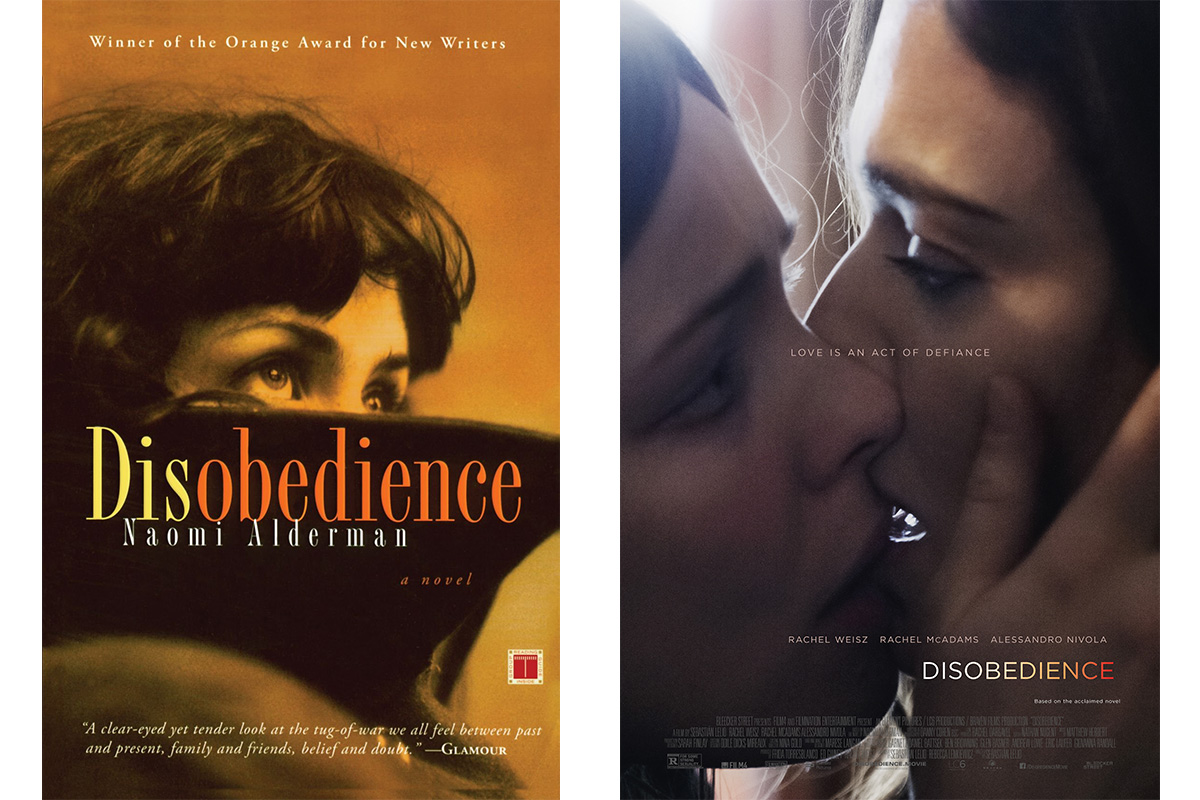

Let’s start with the key art for the book versus the movie:

The book cover focuses on one woman, looking up, in hope? Concern? Fear? You don’t know, but you get the sense it’s about her experience. The pull quote tells us its a “clear-eyed yet tender look at the tug of war we all feel between past and present, family and friends, belief and doubt.”

Not surprisingly, the movie poster is much more sensual: With the tagline, “Love is an act of defiance,” it’s an image of Rachel McAdams (Esti) and Rachel Weisz (Ronit) in serious eye contact as they almost kiss. Immediately, we know two key things: one, the movie focuses much more on the passion of the romance between the women, and two, it does still revolve around the conflict of defying one’s community/past/beliefs.

In the movie, they shift away from Ronit as the center of the story. When I spoke with producer Frida Torresblanco, she explained, “We were taking the story from the point of view of Ronit. So we had to make some adjustments in order to balance the characters, right? We had a very, very strong Ronit perspective, and then we were building Esti’s journey, and then we felt that, in some ways, we need to find the balance. Because it worked like a triangle…” The three of them — Ronit, Esti, and Dovid — do stand on their own. But in making Esti and Dovid’s narratives carry the same weight as Ronit’s, Ronit’s loses the strength of her figuring out her own identity.

Weisz explains, “Everyone can identify with the idea of leaving home and forging your own way. And that’s what Disobedience is really about: the struggle to find out who you are in relation to where you’re from.” But what struck me most about Alderman’s novel wasn’t this universal struggle, but rather the fact it was specifically a queer Jewish love story. At the very end of the book, Ronit reflects on her identity:

I’ve been thinking about two states of being — being gay, being Jewish. They have a lot in common. You don’t choose it, that’s the first thing. If you are, you are. There’s nothing you can do to change it. Some people might deny this, but even if you’re only “a little bit gay” or a “little bit Jewish,” that’s enough for you to identify yourself if you want.

The second thing is that both those states — gayness, Jewishness — are invisible. Which makes it interesting. Because while you don’t have a choice about what you are, you always have a choice about what you show.

The story is about her being queer and Jewish; even though it may resonate, it’s not a universal queer love story. It’s a Jewish one. And this is crucial.

In an interview with Naomi Alderman, in response to a question about how much of her personal experience she drew on in writing the book, she explains, “Like most adults, I know what it is to love, to desire, to have my heart broken, to want someone who doesn’t want me and to be desired by someone whom I do not desire. I have been confused and angry, resentful and cowardly… These are universal experiences, I think, and happen in the world of Orthodox Jews no less than they happen anywhere else.”

Even though Alderman explains that the story touches on very universal themes, and it does, what I took away from Disobedience was a story that was firmly rooted in the world of Orthodox Judaism.

Dovid as a Sympathetic Character

Ronit, the daughter of a rabbi, left their insular community, and Esti stayed behind and ended up marrying their childhood friend, Dovid. When Ronit returns to the community after learning of her father’s death, she ends up staying with Esti and Dovid. In the movie, it is revealed that it’s Esti who found a way to get in touch with Ronit to tell her about her father’s death. In the book, Dovid calls Ronit. This subtle difference — Dovid reaching out to Ronit, versus Esti — is actually a big change. This demonstrates that Dovid and Ronit (who are cousins in the book, but mere acquaintances in the movie) actually have a real relationship.

Dovid easily could’ve been made the villain; he doesn’t want his wife leaving him, he doesn’t want his status as the next rabbi jeopardized, but he cares for Esti and Ronit. Dovid is a really sympathetic character, more so in the book than the movie. He could’ve easily fallen into the trope of “mean religious husband,” but he doesn’t. As Weisz explains regarding the film, “I love the fact that Sebastián doesn’t really have traditional antagonists in this screenplay. Every character in the film contains within them their own antagonist. In a way, they’re their own worst enemies.” Nivola, who plays Dovid, says, “They all mean well, yet they somehow create a messy predicament despite their affection for one another. It’s a totally human situation that’s unavoidable and painful.”

Yes, totally human — but also totally Jewish.

Alderman’s Disobedience alternates between Ronit’s first person and a close third person of Esti and Dovid. When Dovid is reflecting on whether or not he should be the new rabbi, Alderman writes:

He knew that one or two members of the synagogue had gone so far as to ask the Rav, quietly but insistently, if it might not be best if Esti were to leave. They had questioned whether she was a suitable wife for one as near to being the Rav’s successor as Dovid.

The Rav, who had understood that not every relationship is easy, and that easy is not necessarily to be prized above all, had told him of these opinions, so that he might be prepared. Dovid had not passed this news to Esti. He had not attempted to change his behavior, or to influence her to alter hers. His demeanor with her had remained as it had always been and he had borne the glances, the knowing looks, and whispered comments, in the synagogue or on the street.

It is a terrible, wretched thing to love someone whom you know cannot love you. There are things that are more dreadful. There are many human pains more grievous. And yet it remains both terrible and wretched. Like so many things, it is insoluble.

In the book, Dovid understands who Esti is, her history with Ronit, and the constraints of their community. The movie doesn’t give us this same insight into their marriage; we don’t know how much Dovid knows about Esti — we assume he knows there’s a history between them, but that’s all.

After an hour of longing glances, the first kiss between Esti and Ronit happens too late into the film (in my opinion). Esti accompanies Ronit to her father’s house, untouched after his death. Ronit, visibly upset by the state of the house, turns on the radio, and the Cure’s “Lovesong” starts playing. Ronit and Esti slowly bob their heads, and voila, they end up kissing.

In the movie, they sneak away and get caught by a gossipy member of the community. In the book, Dovid walks in on them. Big difference. Yet, in the book, Dovid doesn’t rage at Esti, doesn’t shout, doesn’t get upset. He understands. He realizes she’s struggling to be a part of the community that means so much to her (much of Esti’s narration is reflecting on Judaism and the Torah), and he wants to help as best he can.

In the movie, however, there’s a dramatic scene, where Esti shouts at Dovid, “Look at me! I have always been this way!” She asks for her freedom (only a man can grant a get, a divorce).

Obviously this kind of drama is necessary on the big screen, so I don’t fault the creators, but I am frustrated that Dovid’s quiet understanding was lost in the film.

However, I do think Nivola kept in mind this understanding as he played Dovid. As he explains, “I love the way that Dovid and Esti’s relationship is written because it’s a good marriage and they have a deep respect for one another.” Nivola, in researching the role of Dovid, got to know the Orthodox Jewish community. He explains, “What I discovered was that there are a million shades of grey in terms of how people observe their religion. And because of that, I felt a responsibility throughout the making of the film to capture the incredible warmth of the Orthodox community. These people are full of passion and affection for each other. Although they’re sometimes perceived as isolated and ruthless in their judgment of the outside world, that wasn’t my experience at all.”

At the hesped (eulogy) for the rabbi at the very end of the film, Dovid gives an empassioned speech about how people should have the freedom to choose, and he makes eye contact with Esti and Ronit sitting in the woman’s section of the synagogue. The speech was powerful and moving, and showed Dovid’s compassion for his wife’s struggles, but in the book, the story goes down much differently. Dovid walks up to the women’s section, grabs Esti by the hand, brings her downstairs, and she gives the speech.

I was thrown by this: Why give the powerful moment to Dovid, instead of Esti? Torresblanco explained to me, “It elevated the character of Dovid.” Essentially, it goes back to the triangle she talked about before; having the three characters stand on equal footing because “they were [all] having their own disobedience experience.”

Esti’s Jewishness

The character of Esti, more so than Dovid and Ronit, is true to the book, but we don’t get to really see her connection to Judaism on the screen. Like Nivola playing Dovid, McAdams did her research and the Jewishness was definitely part of her character. As McAdams explains, “I constantly found myself reading the novel and mining it for poetic bits that could help bring additional life to the scenes. Naomi Alderman wrote such rich characters, and I actually ended up hosting it with my book club around the time of Rosh Hashanah.”

But the book dives into her feelings about everything from Shabbat to the mikveh (Jewish ritual bath). One passage from the book, which explains Esti’s hesitation to leave the community with Ronit, only partly made it into the movie:

“Esti, you fancy girls, don’t you?” She nodded.

“And you don’t fancy men, do you?” She shook her head.

“And you’re married to a man, aren’t you?” She nodded again.

I spread my hands wide. “Well, now, Esti, doesn’t there seem to be something wrong with this picture to you?”

She sighed. I waited. Her skin was even whiter than usual, I noticed, and creased under the eyes, at the corners of her mouth. At last, she said: “Do you remember ‘tomorrow is the new moon’? The story of David and Jonathan?” I nodded.

“And do you remember how much David loved Jonathan? He loved him with ‘a love surpassing the love of women.’ Do you remember?”

“Yes, I remember. David loved Jonathan. Jonathan died in battle. David was miserable. The end.”

“No, not the end. The beginning. David had to go on living. He had no choice. Do you remember who he married?”

I had to think about that one. It’d been a good few years since I last learned Torah. I sifted around the facts in my brain and eventually came up with it. “He married Michal. They weren’t very happy. Didn’t she insult him in public, or something?”

“And who was Michal?”

It clicked. I understood. Michal was Jonathan’s sister. The man he loved with all his heart died, and he married his sister. I thought about that for a moment, taking it in. I wondered whether Michal and Jonathan had looked anything like each other. I thought about King David and his grief, his need for someone like Jonathan, near to Jonathan. I was quite moved, until I realized this idea was insane.

What’s so powerful about this scene is yes, Esti loves (loved) Ronit. And she uses stories from the Bible to understand her current situation. Guess which part the film used? The beginning — no mention of the Torah included.

Weisz, in a fantastic conversation with McAdams in Lenny Letter, says, “I genuinely believe Esti’s spirituality — that she really believes in God but she can’t align her Orthodoxy with her sexuality. How did you make me believe that you believe so strongly in God and this religion?” McAdams responds: “I realized how much [Judaism] was a part of who Esti was. She wasn’t willing to give religion up; that never really even occurred to her…. That’s the greatest choice she ever has to make in her life, is between her religion and who she is, which are linked. It was very confusing. As I’m talking about it, I’m still confused. I think everyone can relate to that in a way: The world doesn’t always embrace what you are — you have to try to slot yourself in somewhere. There’s a lot of pain and confusion that comes up in that.”

Can everyone relate to the very specific battle between Orthodox Judaism and her queer identity? Seems unlikely to me, but maybe? But McAdams does touch on one thing I wholeheartedly agree with: the religion is an integral part of who Esti is.

A Universal Story?

As Torresblanco said of the film, there was something “essential” about the story, because no matter what religion you are, “everybody faces this kind of question.” These of themes of love, community, and religion are universal, yes. But: We shouldn’t forget this is a very Jewish story. Ronit, Dovid, and Esti are all defined by their Jewishness — it informs their actions, relationships, and how they interact with the world. To ignore that and say it is “universal” is doing this magnificent queer Jewish love story a disservice.