Hey Alma’s advice column recently tackled a letter from a convert who was curious to know if it’s necessary to disclose the fact that they converted to Judaism. As a convert myself, I loved the supportive tone of the response. While I 100% believe that the column comes to the right conclusions, getting to that point is not always so simple for all Jews who underwent conversion.

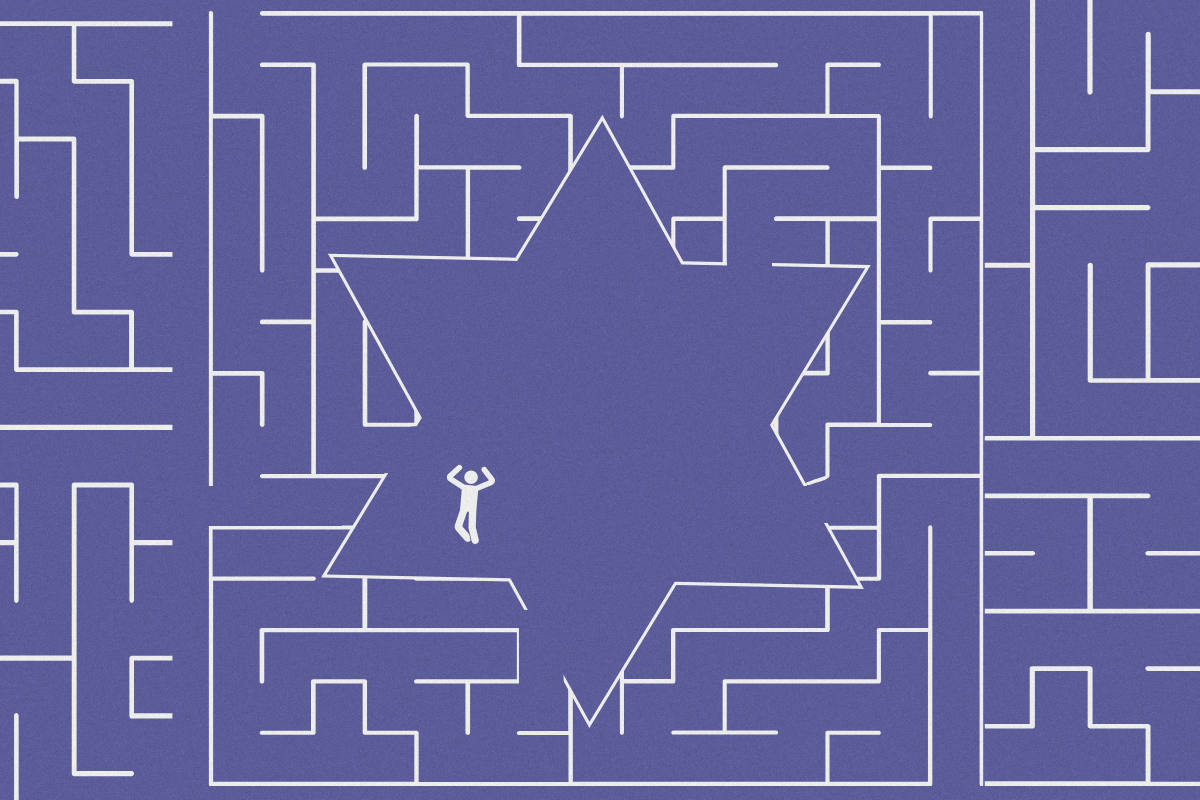

I want to illustrate my point with a metaphor. Please buckle up and get ready to follow along — I promise, it’s worth it.

Imagine that you developed an interest in being a stage actor. It’s something you’ve thought about a lot, something that has always held a great fascination for you. One day you decide to buy a book about the theater, which grows into a whole bookshelf full of them. Still, though, you want more. You take an acting class. Then another. Over time, you practice, learn and slowly work closer to your goal: becoming a professional actor.

Finally, the big day comes. You audition for a role and — to your amazement — you get it! You did it! You are thrilled, but still nervous on the first day of rehearsals. When you arrive, you get a few inquisitive looks, but for the most part, people seem nice. Some smile. A few even introduce themselves. This is going well, you think. This is your dream, after all. Wanting to be brave, you muster your courage and walk up to a group. They nod and smile before going back to their conversation. You realize that they all seem to know each other. Like really well.

You realize that many of them grew up together; they have shared memories to which you can’t relate. You love the theater more than words can describe, and the fact that you weren’t a theater kid growing up actually makes you feel a little sad. Not that your own childhood wasn’t fine, but missing out on the memories described by this group feels like a loss itself, not to mention slightly uncomfortable, since you can’t join the animated discussion.

Quietly excusing yourself, you join another group. You’re bolder this time, and introduce yourself. Everyone is so nice! They strike up a conversation. What other shows have you done? they want to know. Not wanting to lie, you take a deep breath and explain this is actually your first — you only recently became an actor. They are genuinely interested, which manifests through questions. Lots of them. What made you want to be an actor? How long did it take you? Is your partner an actor, too? Did you become an actor for them? Why would anyone want to become an actor, someone joke, it’s miserable!

You know they mean well, but this is overwhelming; you literally met these people 38 seconds ago. What’s worse is that all of your answers feel cliché; they are inadequate to describe the deep call you felt toward the theater. Your new friends look bored.

Luckily, the director arrives and the rehearsal begins. This is it — what you’ve been waiting for. Perhaps not the smoothest start, but it’s okay, because you are here. You are an actor on stage. You did it.

Except, when the director begins, you have a hard time keeping up with her instructions. You spent hours painstakingly studying every aspect of the play, but now it feels like all of that knowledge has vacated your brain. Some of the vocal warm-ups are a little different than the ones you did with your coach. Faster. You can’t quite follow all the lingo and instructions like everyone else does, and you spend the whole rehearsal treading water. You were so jubilant — so confident — when you walked into the theater that morning, but now feel deflated. Will it always be like this? you can’t help but wonder. Will I ever fit in?

Obviously, this is not a perfect analogy, but I hope that it can help clarify the complications, challenges and just plain awkwardness of being a convert in Jewish spaces. So while I appreciate the optimism of the initial advice given by Vanessa, it didn’t truly resonate, which in some ways felt even more alienating. When I wrote to the editors and asked if I could share some advice of my own, as someone with lived experience as a convert, they were excited to let me join the conversation — and I’m excited to expand the topic even further with multiple voices.

I’m lucky to be part of a very supportive Facebook group for converts. When I asked what they thought about this matter, members shared some really insightful words. Benjamin T. McCormick, for instance, wrote that, along with “a strong sense of internalized imposter syndrome,” — I mean, same here — he has occasionally dealt with “an air of snootiness” from people who were born Jewish “By all means, not from everyone,” he clarified, “but there have been a few people who, upon learning of my conversion status, tend to speak to me as if I’m one of the poor cousins from out of town who just doesn’t understand how things work in the civilized big city.” Ruth James related being a convert to her experiences as an adoptee, which she described as experiencing “conditional acceptance.”

C. (who asked me not to use their name) pointed out that while all the positive comments left on social media supporting the letter writer and converts in general are lovely, virtual support doesn’t automatically translate to real-life situations. Perhaps Matt Milner summed it up best when he said: “There are nuances we as converts experience (or are occasionally forcibly introduced to) that simply won’t be apparent to those born Jewish, just as we can’t know what it’s like to have been born Jewish. It doesn’t mean anything is right or wrong, it’s just a different texture to our life experiences.”

Like any facet of an individual’s identity, being a Jew-by-choice has layers of complexity that are not necessarily knowable unless you’ve lived it. Everyone’s relationship with Judaism is unique, and some have more struggles on the path than others. To all the supportive born Jews out there, we so appreciate all the love. Please just remember that there are internal and external forces at play that can impact how easily (or not) we feel accepted by the larger Jewish communities of which we long to be a part.

To fellow Jews-by-choice — remember that your journey and feelings are valid. It might not always be easy, but it will be worth it when you finally find your niche.

And to go back to the original question in the advice column, you asked:

Is it bad form for me not to tell people I’m a convert? And, if someone finds out through someone else that I’m a convert, how might their opinions of me change?

Remember this: You are only a “convert” during the process of converting. Once you emerge from that mikveh, you lose convert status and become a full-blown Jew. You never have to use that term again if it’s one that doesn’t suit you.