The disappointment in my pop’s voice when I returned from Birthright without a betrothal to an IDF soldier was difficult to conceal — not that he tried terribly hard.

So when I married a lapsed Irish Catholic a year later, I was prepared for him to be a little bummed out. He thought I’d be a proud, strong, neurotic, insistent Jewish mother and wife, and that a non-Jewish husband might dampen my resolve.

I, however, was most excited about swapping out my 12-letter, consonant-clustered, impossible-to-spell-or-pronounce, incredibly Jewish last name for a quick, quaint, four-lettered Irish one.

The funny thing is, I never legally made the change. At the time, I told myself I didn’t have a lot of faith in the marriage itself lasting (I was right) and the paperwork was prohibitively difficult and I’d be unwilling to do it twice (I was probably right). But maybe I knew, even then, that I didn’t really want to say goodbye to Schlessinger.

I tried my Irish last name on for about a year. I even changed it on Facebook. People still couldn’t pronounce it, but spelling those four letters was a far cry from sighing and saying, “It’s a doozy. Are you ready? S as in Sam…”

But I didn’t use the new name for long. We split a little over a year after swearing to do this thing until we both died (which I still think is a big ask, no matter how well you know the person).

With the gift of a couple years’ distance, I’ve been able to question myself more honestly about it.

Was all my fuss actually about the spelling and pronouncing and the inconvenience of having to introduce people from my small, red-blooded, East Coast town to their first real-life Jewish name?

Or was I embarrassed?

I went to Hebrew school every Sunday, and to an arts school for high school. I knew other Jews.

But the Hebrew school Jews, and to some extent, the high school Jews, weren’t like me, and I didn’t get their lives any more than they got mine. Perhaps due to that magic quality of socioeconomic proximity, I felt better understood by the neighborhood kids, who went to the same places as I did during summer vacation, and were as likely to get a camera phone for their 13th birthday as I was – not at all.

But none of what the neighborhood kids knew about Jews came from Jews.

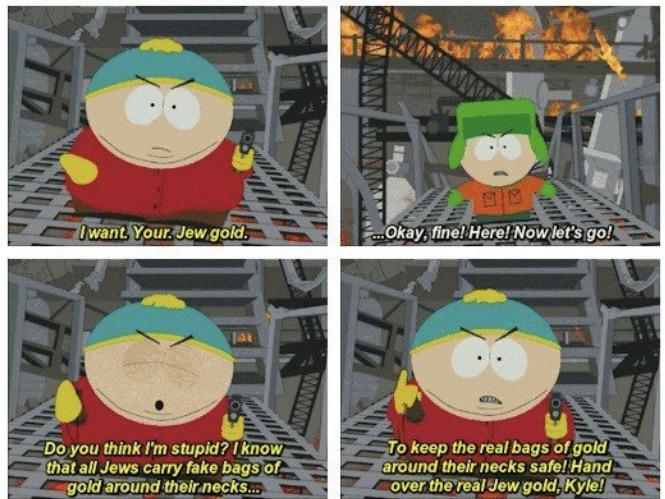

At best, they knew nothing, and I was only responsible for sharing what I thought might sit well with them. At worst, they were cruel. Mostly because of shows like South Park…

(A particularly stinging experience when my Aunt Julie got me a gold Star of David necklace for my bat mitzvah. I didn’t wear it for long.)

For some, their parents repeated right-wing rhetoric they’d heard on network news about Jews. The Holocaust, yes, inexcusable, but also… they do run the banks…

Schlessinger made me “other” at a time when it wasn’t edgy to be “other,” and these kids already thought I was strange, exuberant, and unnecessarily scholastic. It was a signal, and an unwelcome one at that.

For a while, I did my best to separate myself from my Judaism around non-Jews — yes, I’m Jewish, but not like that. I don’t do the silly things that other, more serious Jews do. I’m a kid, just like y’all, and I hate Hanukkah and love Christmas (my mom is Episcopalian, for what it’s worth).

The people I felt closest to my whole life were non-Jews. But those people were also the most dangerous, even if they didn’t feel they were actively bigoted. “Schlessinger” made me the butt of all jokes — sometimes just ignorant and sometimes downright antisemitic jokes.

That Irish dude with the four-letter last name, who didn’t show any interest in Judaism beyond iterating that his mother shouldn’t be advised of the situation, was my perfect chance to get rid of Schlessinger once and for all.

I can’t say for sure if people actually treated me differently when my last name was distinctly Irish and not Ashkenazi. But after a while, I started to notice that I actually missed Schlessinger. It’s long, and complicated, and even Jews disagree on how to pronounce it (we pronounce it Sless-ihn-jer).

But it contains part of my story.

It’s my pop’s parents’ Lithuanian heritage. It’s how other Jews so often recognize they’ve found one of their own. It’s a strange juxtaposition with the extremely Anglo-Saxon first 66% of my name — Lucy Charlotte — which I now find charming in its own way.

And for the sake of the angry God of the Old Testament, you can just learn to pronounce it.

Since I ditched my husband, I don’t warn people when I’m about to spell my name. I don’t say “good enough” when someone butchers it, instead opting to correct their pronunciation.

And if there was a time that it made me nervous to have people know I’m Jewish — even with the rise of antisemitism in the States — that time is surely not now.