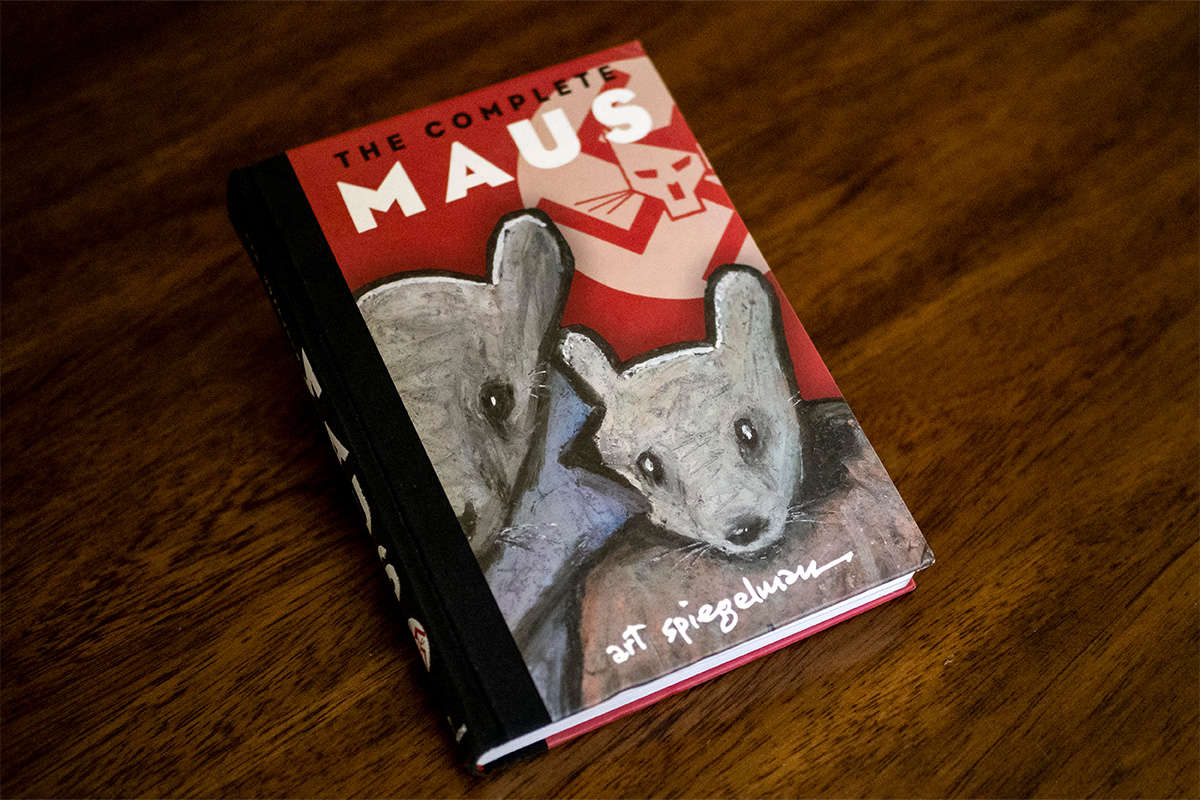

When I heard about the recent decision by the McMinn County School Board to remove “Maus,” a graphic novel memoir about the Holocaust, from their 8th grade curriculum, I immediately began thinking about my own experiences as a Jewish public school student in Tennessee. Although my school district was much larger and more urban than McMinn county, and the curricula aren’t the same, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the way the Holocaust was treated in my own education.

I spent most of my childhood in Tennessee after moving from Seattle the summer before 4th grade. The Jewish community in Nashville is small compared to Seattle’s. I attended a Jewish day school for a couple of years, and once I graduated in 6th grade, I switched to the public school system.

Unlike in Seattle, where I was never the only one to have matzah in my lunchbox in April, I quickly discovered that I was the first Jewish person some of my public school classmates had met. For Jews in areas with large Jewish communities, it is easy to forget that in parts of the country, there are people who have never met a Jewish person. Overall, my classmates and teachers approached my Jewishness with respectful curiosity, but I grew to dread the hassle of missing class for holidays and any world religions unit, where I’d inevitably have to correct a teacher that no, Jesus wasn’t a Jewish prophet.

After my 12th grade English teacher introduced a unit on genocide, she pulled me aside. As one of two Jewish students in my grade, she wanted to make sure that I felt comfortable with her lesson plans. She explained to me that our class would be focusing on how the psychology of genocide played out in different genocides throughout history. And there was another thing: Amongst the different genocides we learned about, we wouldn’t be covering the Holocaust.

The reasoning behind this decision? Most of the students at my school, a public magnet in Nashville, Tennessee, had attended a magnet middle school that fed into our high school. There, the 8th graders had a unit specifically devoted to the Holocaust. My teacher told our class that since most of my classmates were familiar with the Holocaust, but not with other genocides, like the Rwandan or Cambodian genocides, we would be skipping it.

The removal of “Maus” from the McMinn 8th grade curriculum has left me freshly questioning my teacher’s assumption that an 8th grade introduction to the Holocaust was enough.

I did not attend the middle school that most of my high school classmates attended. However, my impression is that the 8th grade Holocaust unit was, to put it mildly, insufficient. In fact, there was more than one Holocaust Joke Incident in my high school class’s GroupMe chat. Clearly, my classmates did not learn enough in 8th grade to understand why it would be inappropriate for a white, Christian student to announce that he wanted to reclaim swastikas as Buddhist imagery, or to understand why jokes about Jews and ovens made me sick to my stomach.

From talking to my one other high school Jewish classmate (who was my boyfriend then and still is now, #highschoolsweethearts), who did attend that middle school, the 8th grade curriculum presented a very sanitized version of the Holocaust. They read “The Diary of Anne Frank,” and “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” the latter of which can especially make non-Jews more comfortable with the Holocaust, as one writer pointed out in a recent viral thread on Twitter. The non-Jewish protaganist of “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” is blissfully ignorant of the systematic murder happening right next to him, and while Anne Frank is surely an important read, her belief that despite it all, people are good at heart — one of the most famous, enduring lines from her diary — allows non-Jewish readers to avoid grappling with the reality that the Holocaust was full of people, regardless of their inherent nature, doing very bad things.

I couldn’t help but contrast that with the Holocaust education I received in Jewish spaces. In 3rd grade Hebrew school, after my classmates and I read poetry written by children our age in the Terezin concentration camp, our teacher shared with us that none of those children had survived. At Jewish day school, my class had a semester-long unit on the Holocaust, where we learned directly from survivors in our community. I knew that even in those spaces, my teachers had protected us from learning about some of the worst atrocities.

There was just no way that my public school classmates had a thorough understanding of the Holocaust.

At the time, I wrote my teacher a letter outlining my discomfort with her rationale behind her decision. Rereading my letter now, my relief and joy at being asked my opinion shines through. I was so used to my Jewishness being treated as an inconvenience at school, like having to explain to teachers that no, I cannot do homework while I’m absent on Yom Kippur. I trusted her a lot, so in my letter, I outlined why omitting the Holocaust from our discussion made me feel so vulnerable. I shared that it felt like another version of being told that my community needed to “get over” the Holocaust, and that I worried that my classmates had only been exposed to sanitized Holocaust narratives that isolated it from thousands of years of systemic persecution. I shared my fear that I would have to become a spokesperson for the Jewish people again. At the time, I wasn’t even bothered by us not covering the Holocaust, but I found the argument, that people already knew about it, to be distressing. Being asked my opinion was such a relief that if anything, I tried to muffle the extent of my discomfort.

Looking back, I disagree with my 12th grade self about one thing. It seems impossible to teach about the psychology that allows genocides to unfold without examining the systematic way that Nazi propaganda created a blueprint for dehumanization and mass murder. A sanitized, child-friendly version of the Holocaust (has there ever been a worse oxymoron for the Jews?) is the stopping place in so many people’s education. McMinn County’s removal of “Maus” from their 8th grade curriculum is far from the only instance of non-Jewish people insisting that the Holocaust is taught in a way that feels comfortable to them.

And I know my home state can do better. In my 6th grade Holocaust class, we took a field trip to Whitwell, Tennessee, the home of the paperclips project. In the ‘90s, 8th graders in the small town took on a project to collect six million paperclips to help visualize the number of Jewish people murdered in the Holocaust. They have since created a small museum, where you can see all of the paperclips inside of a German transport car.

My teacher appreciated the thought that I put into my letter, but she did not change the curriculum, and to the best of my memory, she did not address my concerns with our class. As a result, my classmates were left with the messaging that they learned what there is to know about the Holocaust during one unit in 8th grade.

I chose to do my final presentation about intergenerational trauma in the Jewish community, interviewing friends and relatives. At the beginning of my presentation, I showed my classmates a side-by-side picture of myself at age 7 and Anne Frank. I told them about how, for my entire childhood, adults in my Jewish community had told me how much I looked like her. But at a certain point, right around my bat mitzvah, the comparisons stopped. I was older than she’d ever gotten to be. I told them about the trauma of realizing that, save for 70 years and some geography, her fate could have been mine.

At the time, my story felt important to share as part of my presentation, even though I felt uncharacteristically nervous before I presented. In retrospect, I realize that I felt the need to display my community’s trauma as viscerally as I could to compensate for how our voices were excluded from discussions in class. Sometimes I wonder if what I shared with my classmates had any impact on their understanding of the Holocaust. Sometimes I wonder how much they think they understand.