In my view, there are two major truths about names. First, they hold power. We as humans deeply identify with the names we carry, and to be called the wrong name can be a deep violation. Second, names are often treated as preordained, immovable markers — a connection made at birth and cemented from then on. Thus, in the eyes of some, the changing of a first name is treated like heresy. (Ironically, the most accepted name change is the traditional concession of a woman’s surname in marriage.)

So, I guess that makes me a heretic.

I have changed my name twice in my life, not due to marriage or witness protection, but because I felt a disconnect between the name I carried and the person I am. This is a ubiquitous experience for many trans people like myself, and although a name change comes with deep joy and relief, it is an equally frustrating and humiliating experience. Changing one’s name legally, for example, often requires a grilling process of forms and applications that not only take up time and money but a vast amount of emotional energy. There is then the toil of changing your name socially. Although all your legal papers can be changed at once, you end up walking the world feeling a little fragmented, identified both as both your past and present self at once.

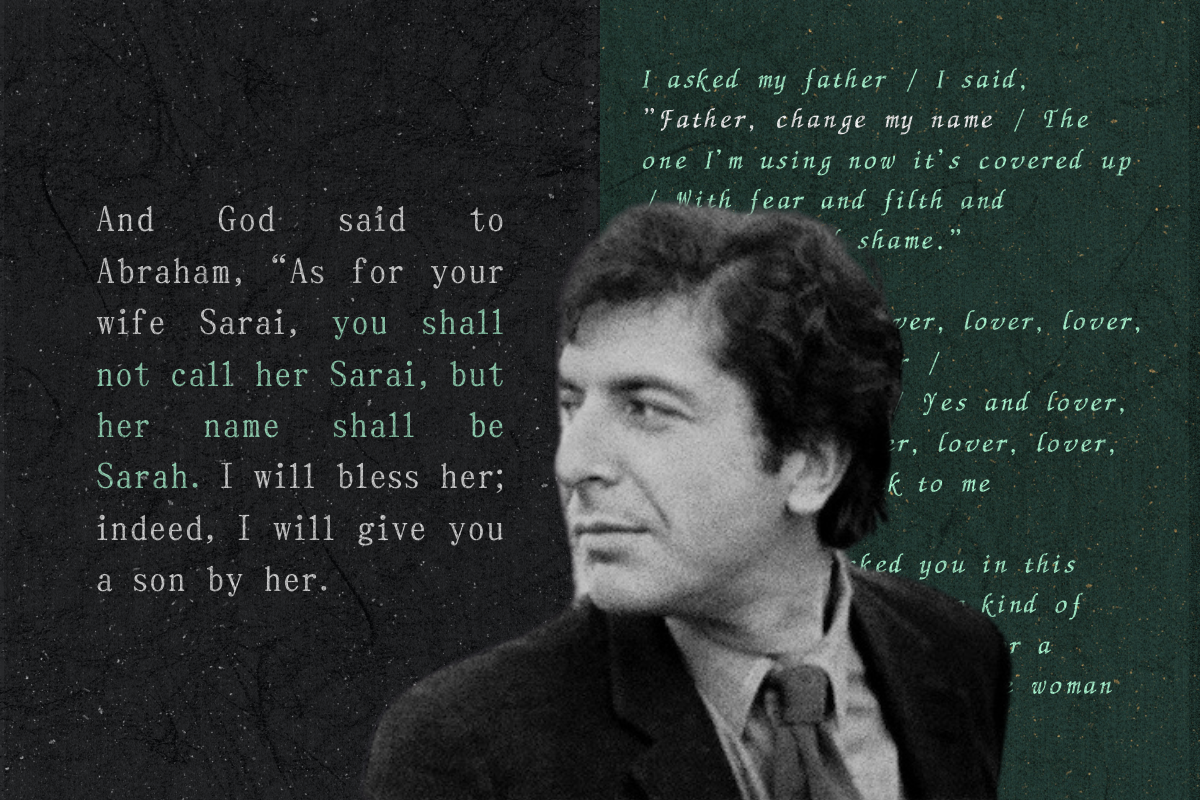

But what other people called me was not the biggest of my concerns. Instead, I became obsessed with understanding how God thought of me — which name God used for me. Prayer became an interesting exercise of wanting complete submission to the words and moment while keeping the deep anxiety over my name at bay. I would often find myself thinking of Leonard Cohen’s “Lover, Lover, Lover.” Written about Cohen’s experience performing for Israeli troops in the desert during the Yom Kippur War, I related to the desperation in the opening lines as he sang, “I asked my father / I said, ‘Father change my name.’ / The one I’m using now it’s covered up / with fear and filth and cowardice and shame.”

The names I left behind felt burdened with the shame of another person I had pretended to be, and it worried me — especially the lingering of the name in private places in my life, like my relationship with God.

Considering the great amount of emphasis that Judaism puts on names, it was no surprise when I first came upon a tractate of the Talmud which specifically mentions name changes. Reading it, I instantly saw the implications.

Rosh Hashanah 16b discusses the laws of the holiday of its namesake. One of the main concerns of the sages was the Book of Life, based upon which God decrees our fates for the coming year. During the time before Rosh Hashanah, Jews are meant to not only reflect on the actions of the year passed, but also deeply concern themselves with the coming of the next one.

The Gemara, one part of the Talmud, tells us of a teaching of Rabbi Yitzhak on the “tearing” up of divine decree against a person, essentially changing their fate. It states there are four ways to change your fate: give charity, cry out in prayer, change one’s name and change one’s deeds for the better. The third one stands out and directly emphasizes the importance of a name. To change one’s name is to defy divine decree, to effectively turn to whichever angel that’s been sent to fulfill God’s will for you, and simply tell them, “You have the wrong person.”

Obviously, I do not mean to equate my name change with the avoidance of a Godly decree. Rather, I seek to demonstrate the extent to which one’s name change permeates their identity in Judaism — effectively creating a new person unrecognizable to a divine decree and by extension, to God. If I could turn to an angel and tell them that the name they asked for is no longer mine, and know that they are satisfied, then I would know that my name change meant something.

Clearly, angels have been satisfied in the past. The Gemara justifies the religious weight of a name change by citing the lives of Avraham and Sarah:

“[…] a change of one’s name, as it is written: ‘As for Sarai your wife, you shall not call her name Sarai, but Sarah shall her name be’ (Genesis 17:15), and it is written there: ‘And I will bless her, and I will also give you a son from her’ (Genesis 17:16) […]”

Many trans Jews have found comfort in the story of the first patriarch and matriarch, recognizing the moment of their name changes as a relatable trans experience. Moreover, this passage of the Talmud insists on the name change as a reflection of a fundamental change in how the person meets the world. Additionally, it places us directly within our people’s mythological lineage, drawing a straight line between us and the covenant that was a precursor to us as a nation.

By bridging the space between the first lines of Cohen’s “Lover, Lover, Lover” and Rosh Hashanah 16b, I have found not only comfort but power in my name change. I still find myself sometimes crying when listening to “Lover, Lover, Lover” but they’re no longer tears of incongruency, but rather ones of deep self-identification. I am not asking anyone to allow me to take up space as Benyamin — but instead to see my name as a definitive marker of a change in the way I meet the world.