Growing up, at every Shabbat, my dad would ask us why we say the same prayers repeatedly. My brothers and I would answer, “To pass on to our children.” In the face of diaspora and genocide, our connection to our ancestors comes through tradition passed between generations of family. So it’s no surprise that, as Jews, we spend a lot of time thinking about ancestry.

The Jewish side of my family has been particularly blessed in that we have a Torah that my great-great-grandfather escaped Germany with, filled with the genealogy of my family tree. The Jewish cemetery of the village my family is from is filled with intact headstones of past family members, and I have sat in the grass of the cemetery and left stones for my ancestors.

And yet, at some point, I felt like something was missing. As I grew as a Jewish feminist, poet and practitioner of Jewish magic and plant medicine, I began to wonder about all the ancestors I was missing. I don’t have stories about kitchen healers, about my ancestors who worked at the edge of the Black Forest foraging for natural remedies.

I feel an intense sense of loss when I think of my ancestry. And I know I am not alone in this. For those of us who exist in the margins of Judaism, be that by gender or sexuality, or as chosen Jews, much of our history has not been preserved. Our ancestors did their work outside of Jewish institutions, orally passing down many of their practices. And so, we have the bittersweet but beautiful opportunity to expand our definition of an ancestor — and even create our own.

This is what I attempted to do with my poetry book, “Sheologies.” The poems found within are fantastical, but are also an invitation to engage with the ancient technologies of Jewish magic, prayer and mystical text to locate our present-day and past ancestors and create new rituals.

The work of finding your own ancestors is for anyone who feels a sense of loss when it comes to ancestry, a loss of folk practices, or who wants to connect with the past, and the plant world, while creating your own collective rituals. It is for anyone who wants to engage in a lineage of healing work in the kitchen, in the garden and in Jewish community. It is about claiming ancestry, and ourselves as future ancestors. Writing “Sheologies” was incredibly cathartic and empowering for me, and I want to share some of the ways I learned to create and claim my own lost ancestors.

As I share these, please note that I place myself in a lineage of Jewish artists, healers, herbalists and priestesses, but ancestor work is deeply personal, and finding points of access that feel spiritually healthy for you is essential.

1. Choosing a lineage of Jewish artists

As a writer, my work begins with reading. I have the incredible opportunity to choose what work my writing is in conversation with and discover texts that make my DNA hum. While we are blessed to have rich lineage of Jewish writers, I will note a couple here who especially speak to me.

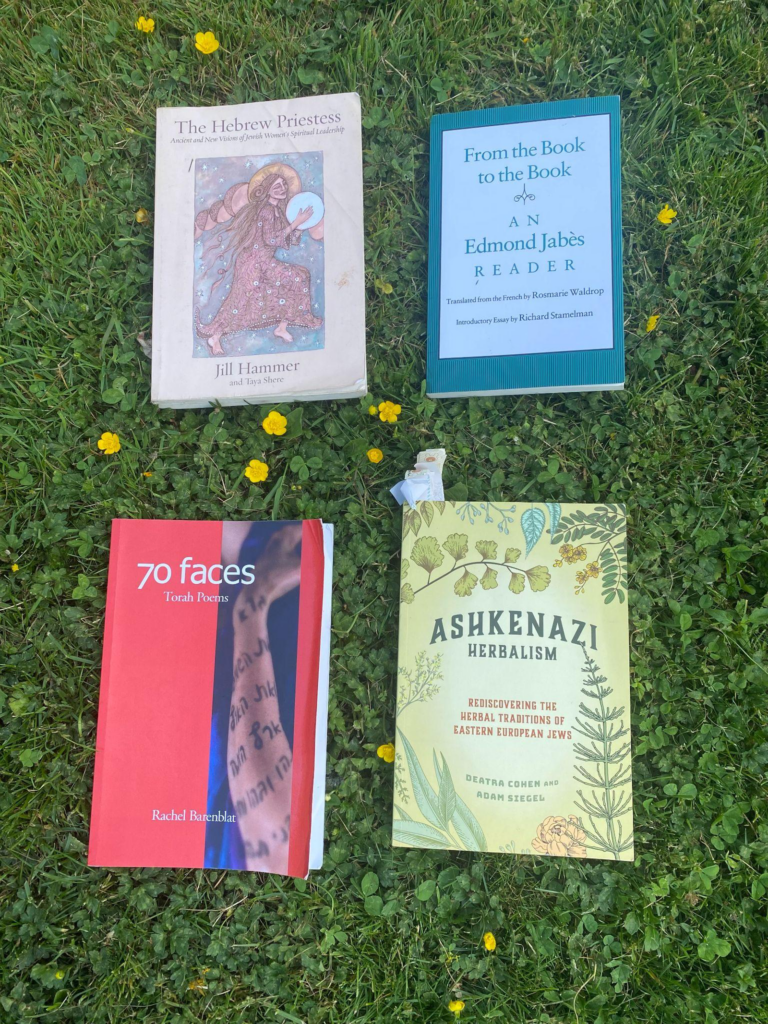

First off, “Ashkenazi Herbalism” by Deatra Cohen and Adam Seigel confirmed my sneaking suspicion that my feminine ancestors created medicine with peonies.

I’d always wondered where my interest in writing fantastical Jewish poetry and hybrid work came from until I read “From the Book to the Book” by Edmond Jabés, translated by Rosemarie Waldrop. This Jewish surrealism hybrid work is how I learned my own work already exists in a gorgeous fantastical Jewish canon, and it’s why I claim Jabés as a literary ancestor of mine.

You know those books you return to for years? For me, two are “70 Faces” by Rachel Barenblat and “Coming to Writing and Other Essays” by Héléne Cixous. “70 Faces” taught me about the concept of Jewish feminist midrash as poetry. “Coming to Writing” empowered me to know that to write as a woman is to write of the body; my breathing is living Torah. I’ve claimed both Cixous and Barenblat as living ancestors (Rabbi Rachel Barenblat even reviewed my book!) and I believe we all have access to this kind of choice; we can expand our definition of ancestry outside of a linear timeline.

2. Connecting yourself to Jewish priestess archetypes

If you, too, feel like you come from a lineage of Jewish healers and practitioners of plant medicine, finding archetypes you can connect to can be a beautiful practice and one that allows you to connect with a sense of spirit, if not name. Rabbi Jill Hammer is the creator of the Kohenet Institute, a program that ordains women and non-binary folk as Hebrew priestesses. In her book “The Hebrew Priestess,” she examines historical antecedents of past priestesses and shares the personal experiences of women who have embarked on contemporary journeys to become priestesses. Her book offers 13 models of spiritual leadership as a Hebrew priestess, including mother, prophetess, mourning woman and midwife.

I personally feel drawn to the archetype of the midwife and consider her one of my ancestors. “She is linked to growth, trees, animals, and everything that springs from the earth,” Hammer writes.

3. Find your plantcestors

I have written about meeting your plantcestors in the past, but it is an ongoing and growing practice for me. The most basic version of finding your plantcestors is to go on a walk to see if you feel drawn to any plants. The chances are that your ancestors worked with that plant in their folk practices, and you can fact-check this through your own research.

But there are many ways to find and talk to your plantcestors. One, of course, is to grow a garden with plants like strawberries (yes, strawberries!) and garlic. Surround yourself with Jewish plants! I’m currently in the process of reclaiming the Wandering Jew or Inch Plant. The Wandering Jew’s name is very antisemitic, based on a tale about a Jew being cursed to wander forever (completely ignoring our history of genocide and diaspora). I recently got a beautiful one and I renamed it The Wondering Jew and have it hanging in what I feel is my first permanent home as a reminder that part of my practice as a Jew is one of wonderment.

And then, there is working with plants through syrups, medicines and essences. You can also engage with your ancestors through art practices. Sometimes on a windy walk, I will stand next to a plant and try to mirror its movements with my body as a form of connection. I write of plants often, trying to tune into what I believe they are saying.

There is no science to this — these are my own folk practices, but they are also an invitation to create your own. Through engaging with my own desire for a more expansive definition of ancestry, I’ve been drawn to what feels like very liberating and creative practices of both ancestor reclamation and creation.

For me, these practices are directly tied to my writing and my poetry, but you may connect them to any aspect of your spiritual and artistic interests. And, of course, all of this prepares us to become the ancestors we so desperately need and want for future generations: magical, nourishing, eco-feminist Jewish badasses.