My last name is complicated; most people can’t pronounce it. It’s long, very Jewish and defies the “i” before “e” grammatical rule.

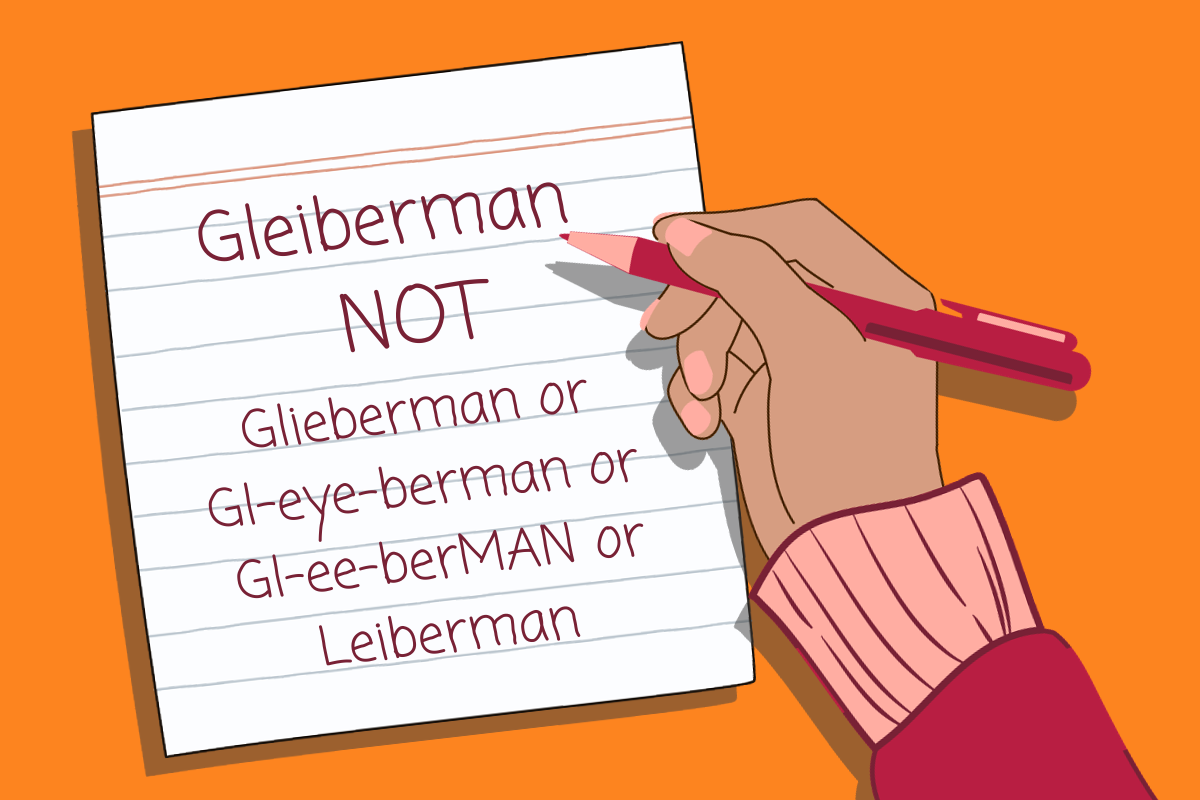

It is pronounced “Gl-ee-berman,” but I have heard just about every iteration there is: “Gl-eye-berman,”“Gl-ee-berMAN” or my personal favorite, “Are you sure it’s not just Leiberman?”

It has been a pain throughout most of my life, especially as a kid — I was singled out every time we had a substitute teacher who inevitably couldn’t pronounce my last name. It would go something like this: “Mary Garcia,” “here,” “David Gardner,” “here.” Then a long pause that turned into an even longer pause and then the usual fumble of pronunciation while everyone stared and my cheeks grew hot. Eventually, when I got older, I just began to yell out: “It’s pronounced ‘Gl-ee-berman,’ and yes, I’m here.”

Now, at the age of 31, I am recently engaged and have come face-to-face with the question that people like to ask as soon as you show them the ring: “Are you going to take his last name?” I’m sure it’s a complicated question for many people, but it feels especially loaded for me. My fiancé is half Puerto Rican, and so am I; taking his last name would mean that I am not necessarily getting rid of a part of myself but embracing another side of me, a side that has never been reflected in my name before.

My fiancé is the love of my life: He is my person, my missing puzzle piece and all the other cheesy things that I would have snort-laughed at long ago before I met him, but it’s true. He doesn’t care what I decide to do, but I love the idea of us being a unit. For me, taking on his last name would feel like love, not like an antiquated obligation.

But I feel hesitant. A part of me feels I am giving up something larger than just my last name, like I am mourning something other than just the loss of a name I have had my whole life.

There aren’t many Gleibermans. The only other Gleibermans here in the U.S. are related to us in some way, according to my zayde.

As I have grown older, I have become more connected to my Jewish culture than I was in the past. As a kid, I mostly just resisted going to synagogue and Hebrew school because it was something that was being forced upon me — and I thought it was boring. I still felt Jewish, but I couldn’t really tell you why.

When I reached my 20s, my Jewish identity began to take shape, and by my late 20s, I found myself reversing generational trauma that taught me to hide my Judaism. I would say my “bubbe” instead of my “grandma” because I finally learned not to care about other people’s discomfort. I would correct people who said “Merry Christmas” instead of just saying “Thank you” like I was taught by my parents and extended family. I would make my identity visible instead of trying to remain invisible in order to avoid persecution. Visibility didn’t come without repercussions, but I didn’t care. Being true to my Jewish identity became the most important thing for me.

Wisdom has come with age, along with a few gray hairs (11 to be exact), and I’ve realized identity cannot be defined by how often you go to synagogue like I thought when I was a kid. It’s not that simple. It isn’t even defined by religion at all for me. It is enmeshed in me, along with all of the other things that make me, me. And along with that has come with it a fierce sense of pride, one that has only grown stronger the older I have become.

I think a strong part of this has to do with where I live. Growing up, I lived in a suburb of a large city that had a thriving Jewish population. There was a sense of “otherness” from time to time, but I was never the only Jew in the room.

Eventually, I settled in a smaller Florida college town, where I have remained for the past ten years. We are a small blue dot in a sea of red, and with this reality has come a strong feeling of “otherness.” Throughout my time here, the number of Jews I have met can be counted on one hand. In the various places I have worked, I have been the only Jewish person and, in a lot of instances, the first Jewish person some people have met, which was a new experience for me.

I have felt ostracized in ways I’d never felt before. I’ve experienced some microaggressions in my life, but I’ve experienced more in the past few years than any time before. I also experienced blatant antisemitism for the first time — it was so extreme that I had to leave my job.

I grew up in a protected bubble of a large Jewish community, without ever having to experience what life is like without that protection. As such, I realized the importance of embracing my Jewish identity more than ever before. The more backlash I received for my Jewish identity, the more empowered I became.

I am proud of my long and complicated last name; I don’t care that most people can’t pronounce it. I am proud of being one of the few Gleibermans left and I simply do not know if I can part with my Jewish last name.

I want to make sure I leave something lasting. I want to leave my mark as a Gleiberman, to one day have my byline in The New York Times or The Atlantic or perhaps author a novel. I want to stick it to the persecutors of the past, present and future, to show that we have not been defeated and we will not be silenced.

I want to say it’s pronounced “Gl-ee-berman,” and yes, I’m here.