In the 1950s, Benjamin Meth, a pharmacist in New York City, happened upon an impressive synagogue. When he thought he would pop in and see what the inside looked like, he was turned away. Why? The practice of the synagogue at the time was to remove your head coverings out of respect, while Meth, my grandfather, preferred to keep his hat on, out of respect. He never got to see the inside of the building. He also never got to meet his grandchildren, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care about his story. Benjamin and Ida Meth, my grandparents, were Holocaust survivors, invited to a life in New York after the war.

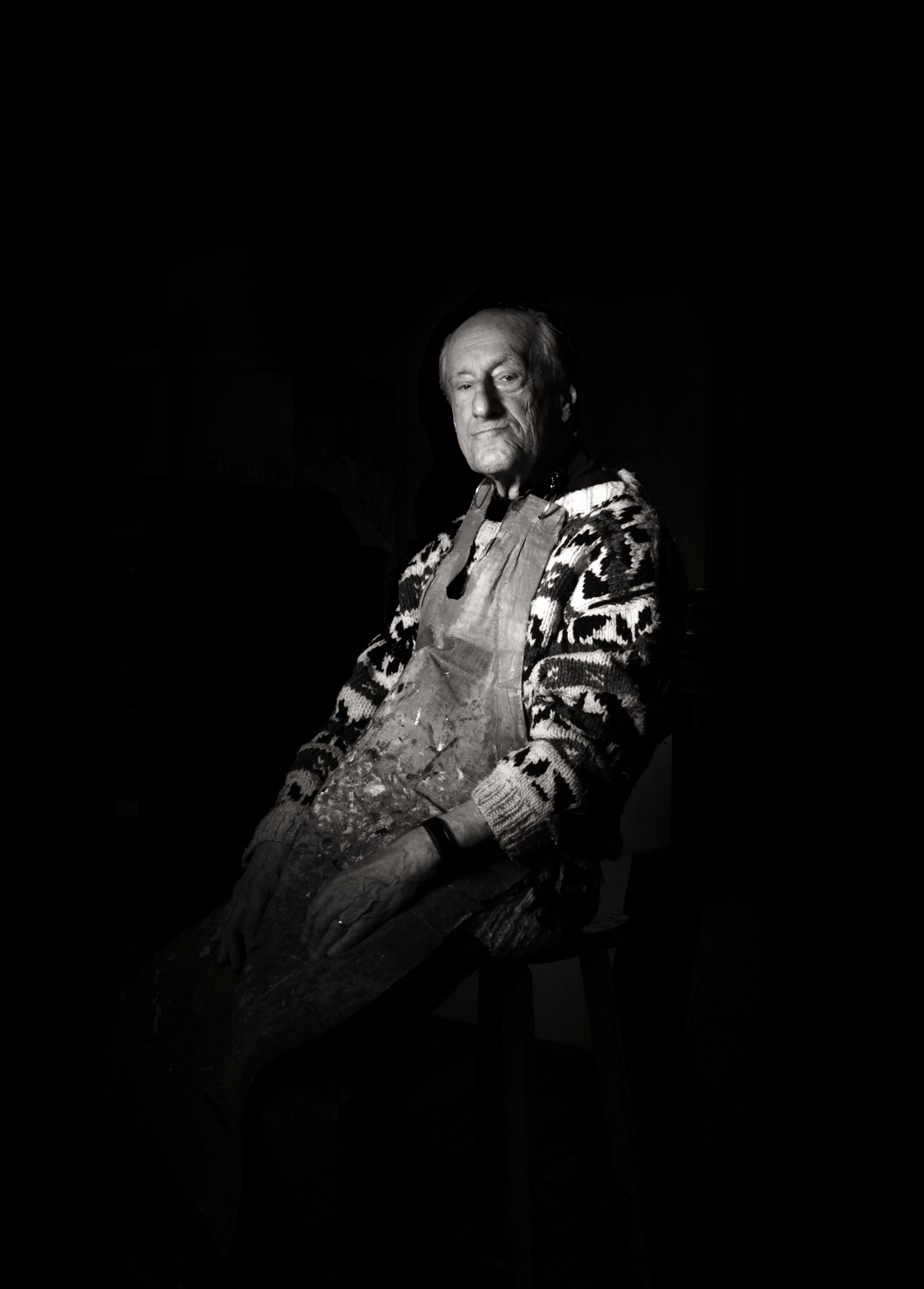

Photographer and writer B.A. Van Sise’s latest book, “Invited to Life,” is a collection of portraits of Holocaust survivors, paired with brief essays about their lives after the war. The photography and the essays take you on a journey through space, time, joy, loss and rebirth. In reading through the pages, you can imagine him sitting down for tea with your Bubbe, bantering with your uncle in Italian, and thumb wrestling a kid while chatting up their mom at the perfect desert location for a photo that encapsulates the experience of their centenarian paterfamilias from Lithuania. (I made that last sentence up, but wouldn’t put any of it past B.A. Van Sise.)

I imagine him comparing hats with my grandfather, who died long before I was born.

Beyond photography, B.A. is also a writer, teacher, poet and proud member of the US Coast Guard. I’ve had a chance to get to know him as a smoked fish enthusiast, bagel connoisseur and friend, in addition to reading and being impacted by his work — especially his photography and writing. Thoughtful, kind and insightful, his work is, at different points, breathtaking, hilarious and gut-wrenching. It’s always worth your attention.

I chatted with B.A. over email and Instagram about his book, his identity and what’s next for him.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What inspired you to interview and photograph Holocaust survivors — after poets and comedians?

I’d say each of my projects affects the next, but actually “Invited to Life” is chronologically the first of them. In 2015, I was working at the Village Voice, and there was a candidate for President who was talking a lot about refugees — especially Mexican refugees — and it was creating a lot of really troubling public dialogue. There was a lot of “they’re not Americans” and “we need to build a wall to keep us free” and “they’re not sending their best people.” I wanted to do a very brief, pointed exploration of what refugees in America look like at the end of their lives, what those lives in America look like.

The various war refugees of the ‘80s and ‘90s were way too young to fully look back on their lives; the Cuban refugees from the late ‘50s/early ‘60s (my original choice) were not quite there yet either. Holocaust survivors — who’d been through the worst trauma possible, and had often had particularly rich and complicated American lives — were the right age. I asked the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York to help me find a dozen or so survivors for the spread; I ended up interviewing and photographing 37. I then put it on a shelf and went to other projects, including “Children of Grass” (my big exploration of notable poets) and a bunch of other stuff.

When the pandemic hit, I was (as I’d always been) financing my life and personal projects through travel assignments and a dozen or so weddings a year. Suddenly, there was no travel. And love? Forget it. I was despondent. Ruined! And my mind kept gravitating, perhaps obsessively, back to the survivors I’d met five years earlier. People who’d been through far worse than I ever had. And they’d rebuilt, forged new paths. Survived and even thrived. I wanted to explore that. Over the course of the pandemic, I bumped that number up from 37 to 140. It was a fascinating time to be doing it, too. I noticed that the survivors tended to be reacting to the pandemic very differently from the world around them. It provided a grounding influence.

It’s also really guided my other projects over the years: Fundamentally, before all else, “Invited to Life” is about trauma response. The two big projects that have followed it have been about comedians — and that job is all about processing trauma — and now I’m working with endangered language speakers who, like Holocaust survivors, know everything about being in short supply. I definitely carry a bit of each project into the next.

“Invited to Life” has a lot of humor in it. “Funny-Looking” (the comedian project, which I put down during the pandemic but am coming back to next) focuses heavily on trauma; “On the National Language” is about the struggle to bring the past into the future. Like a lot of artists, I think the DNA of my work is cumulative.

How do you identify, religiously and ethnically? And how does who you are come into your work?

I’ve contented myself to not really allow my ethnicity or personal experience to step too far into my work. My first published project was about poets, my second was about athletes, my third about Holocaust survivors, my current thing is about endangered language speakers (not exclusively, but it’s America, so more than half are Native) and then I’m going back to comedians. Nobody’s ever given me a Pulitzer, I wasn’t alive during World War II, I’m not Amish, I’m not funny and there are few more miserable sights on the planet earth than watching me try to play sports.

Religiously, I suppose I’m a humanist. It’s not a bad church to belong to: We’ve got Kurt Vonnegut, Joyce Carol Oates and Satan.

What was the worst part of making the book?

I was served so many fucking delicious cookies by so many fucking nice little old ladies that I nearly burst. And I had to get a giant swab stuck up my nose every two to three days for two years straight.

But the worst part? I’ll put it delicately as I’m able, but in the time between the first group of photographs and the second, another photographer put up as an exhibition and published a group of photographs of Holocaust survivors living in Israel that is… well, how people tend to treat survivors: as weaklings, as victims, as impossibly old and feeble. A lot of the survivors had seen them, and I had to explain to them that no, I wasn’t him; that no, I wasn’t out to make them look bad; and that, in fact, I wanted to tell their stories more fully. It created a huge trust gap that I had to overcome again and again. My only saving grace was that the Museum of Jewish Heritage had put up a whole bunch of my portraits from the first batch on their exterior that a lot of survivors had seen or knew about, so I could say, “You know those pictures? Those are mine.” But still: Convincing people who are all 170 years old to meet me during the middle of a pandemic was no problem. Convincing them I wasn’t out to, as some/so many photographers like to do, re-dehumanize them? That was a challenge.

One of my favorite phrases of yours is “he became his admirers” once a person passes away. Can you talk a bit about how you carry your subjects with you, especially as they approach end of life?

The line is from W.H. Auden, regarding the death of W.B. Yeats: “The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers.” I think, in most ways, that’s the most we can hope for: At some point, our computer fails and the rest of us fades to soil, and the best we can hope for is to be carried on in the high estimations of our admirers, that our memory might be a blessing for those who knew us.

It didn’t occur to me, when I started “Invited to Life,” that I was about to make a bunch of friends — and a lot of them truly became friends — just to watch them immediately die. Of the 140 survivors I’ve photographed, 49 have become their admirers, 24 of them just in the time from my delivering the book to the publisher to today. It doesn’t make me sad, though. Funny as it sounds, I’m grateful.

I photographed a survivor named Irving Roth (whose story closes the book) and he became his admirers — of which I am surely one — only a couple weeks later. (He, in fact, busted out of the hospital to come to our shoot; he even had on his wrist that little white LoJack band they give you. He was on his way out and now, in hindsight, it’s obvious to me he knew that.) During our time together — we met and talked for, I think, four hours — he told me all about his great-granddaughter, Addie, who was sitting on his knee for part of the interview. She, born in the 2010s, is liable to live to see a hundred. She’ll have met him, heard his story and may carry it into a century two removed from the one that made him. There’s something to that. I’ve made this book and they’ll make enough copies of it that it’ll outlive me for centuries. And I get to make more, and more, and more admirers for these folks.

I carry a lot of them with me; I feel blessed to have gotten to know so many, to become friends with them. To eat with them and spend time with them. Occasionally these folks just call me to say hi, see what I’m working on. I got to tell a side of their experience that’s unbelievably overlooked, and… I get a bit emotional even thinking about it. I’m overwhelmed all the time by how honored I am in all of this. There’s a decadence, a wealth I feel in how much time was given to me by people who didn’t have a lot of it.

Seven years ago, right at the very, very beginning of this, I dragged my best friend with me as my fake assistant for a day of doing these shoots. We met a woman named Helena Weinrauch who had one of the worst Holocaust stories you could ever imagine, but whose smile had more light than Vegas, and who’d taken up ballroom dancing with handsome young men in her 90s. She, to me, is this project: how a woman can get from concentration camps to ballroom dancing with hunks. To tell that story into the future: That’s my job. That’s why I’m here. I’m her admirers.

Many Holocaust survivors are held up as examples for us, but not everyone in the book was a hero, and you didn’t gloss over that. I have to ask — what was it like to photograph and interview people who were far from model citizens?

Same as anybody else. But no cookies.

I had a grandmother once who was fond of saying “give anybody long enough, and eventually they’ll surprise you.” I suspect that most people who read “Invited to Life” might want to talk about one or two stories in particular. But the truth is that all these people lived lives as diverse as any other group, with the rights and privileges and challenges and pratfalls of any other group. And why not? They came from backgrounds that were varied: different religions, different ethnicities, different sexual orientations, different locations, different experiences. And, as every group has the right to do, they all made their own choices. They’ve the right to make heroes. They have the right to make villains. There are a lot of survivors I admire who certainly did despicable things in their lives: In particular, a lot of them ruined their early marriages while they tried to turn over their capsized lives, and that’s addressed pretty head-on. And if there are survivors who I think have fallen short, I’m sure they’ve done something good in their lives. I absolutely — no exceptions — went in wanting to give everybody the benefit of the doubt. But there were a few — the thinnest of ratios — who went out of their way to leave no question that their gray clouds were low on silver lining. It would have been disingenuous to tell their stories differently.

It’s a dangerous time to be Jewish — I know you’ve gotten some hate mail for your work and for the way your face looks. What do you want to say to today’s Nazis? To young Jews?

I’ve gotten mail from Jewish people who are angry that there are non-white Jews depicted in “Invited to Life.” I’ve gotten mail from white supremacists angry that I’m fulfilling some sort of Zionist agenda. I’ve gotten mail from Black Hebrew Israelites who are mad about the same. I’ve had a couple of people call my house. There was a thread recently on one of the big neo-Nazi websites where they started talking about “Invited to Life” and how, based on my name, I must be a “race traitor.” Then they started trawling through my Facebook and found pictures of, as you delicately put it, my face. They had opinions.

It’s gotta get pretty darn bad for this sort of stuff to filter down to me.

I reject, in small part, your premise: I think it’s a prickly time to be anybody. The rhetoric is turned all the way up, across the board. But yes, I certainly agree (and don’t think there’s room for debate) that there’s a lot more social antisemitism and it’s absolutely, positively increasing. And it’s not finished. The easiest sale in the world is to take any group of people and tell them that their problems are the cause of some vague, hard-to-define “them.” That’s entirely what’s happening at this very moment.

To young Jews, I’d say this: I know 140 Holocaust survivors, people who know more about pain and suffering and trauma than any of us. And they’ve known fear. Endless fear. Fear on tap. And I think that every single one of them believes in the idea of staying vigilant — but also, almost all of them worked to make surviving, thriving lives for themselves in spite of all of it. There’s no reason the same can’t be said for young folks today: Keep vigilant. Find joy.

If I were talking to today’s Nazis — and hey, they email me, I am — I’d say this: What… the hell… is the point? Each of us is given one precious life; why in the world would you waste it being angry all the time, harassing people all the time? You’ve got big opinions? That’s very nice. Join the club. One day this’ll all be over; your computer will turn off, you’ll become soil and you’ll remember none of this. What admirers will you possibly become? Why are you wasting your time on all this, when you could be at the park kissing people or seeing a movie or, or, or?

Your newest work is about photographing speakers of languages: “On the National Language.” What’s the narrative thread that holds “Invited to Life” together?

The publisher of “Invited to Life” let me get away with almost everything I asked for, save one thing: the title. The phrase “finding hope” was their addition. (For most of the time I was working on the project, it was “Refugee: Invited to Life” and then “Invited to Life: After the Holocaust” while I was writing the text.) But they’re not, generally speaking, wrong. There are a few stories in the book that are less than hopeful (two, in particular, leap to mind) but in reality, most of these folks did find futures worth hoping for. They had interesting careers, interesting lives, found love, had families and made new joys — made is the word — for themselves. A lot of folks just want to talk about the terrible years they spent during the war, but these folks also have seven or eight decades after it. I don’t know that I’d be able to feed or bathe myself, do literally anything at all if I went through what they did, but… they managed. Humans have just a phenomenal capacity.

So the narrative thread, such as it is, is this: This is a book about refugees who got a second chance. It’s about what happens to people who are offered the opportunity to — as Yehuda Amichai put it — be invited to life, and take it.

“Invited to Life: Finding Hope after the Holocaust” comes out on January 27th, Holocaust Remembrance Day.