As I tossed and turned last night in my challah crumb-coated bed, I couldn’t help but wonder — is Shrek Jewish? It’s a question the Jewish internet has been speculating on for a while, and after scrolling through an unprecedented influx of tweets questioning the fictional ogre’s religion, I did what any investigative journalist would do. I opened TweetDeck and jumped down the rabbit hole.

“There’s no way Shrek is circumcised,” @jaboukie claimed.

“Shrek is Jewish so I reckon he actually is circumcised,” @ReverendDrDash countered.

“Called my mom to check on her and we wound up arguing over whether Shrek is Jewish,” @BenMekler reported.

“Shrek is based on the book by William Steig, the son of Jewish immigrants,” Twitter user @keepingfeet astutely observed. “None of this is surprising.”

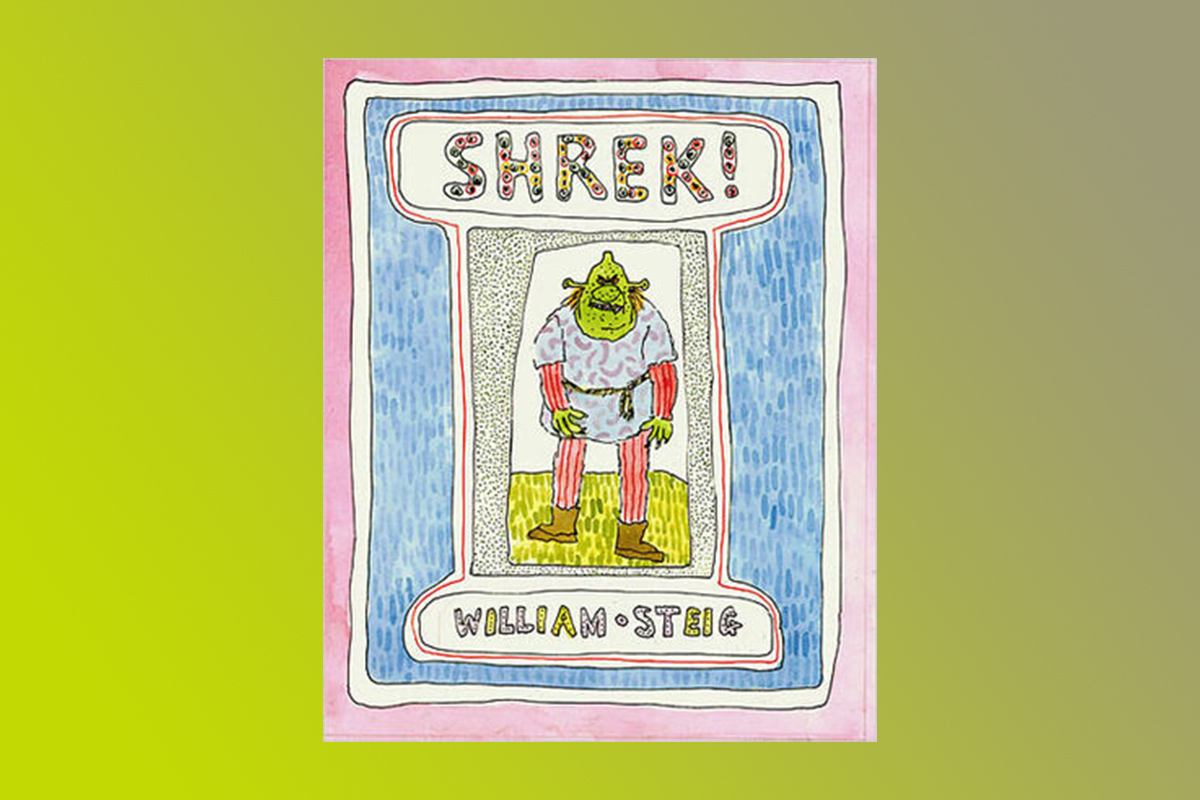

I suppose it isn’t. Like most fairytale stories tinkered and toyed with by big animation studios, DreamWorks’ narrative for the repulsive, swamp-living ogre can be traced back to a primary source. But unlike most “happily ever after” tropes, the father of the original story — and the first sole-creator of an animated movie franchise that accrued over a billion dollars after just one sequel — was a super hot Jewish New Yorker from the turn of the century. (Like, super hot.)

Born to Eastern European Jewish immigrants in 1903, William Steig ruled New York City as the “King of Cartoons.” When the Polish family lost everything during the Depression, Steig sold a whimsical comic to the New Yorker and subsequently fell into a 73-year stint with the magazine. A prolific cartoonist, the Jewish artist from the Bronx subsequently shifted focus from drawing adult-oriented work — featuring “satyrs, damsels, dogs and drunks” — to writing children’s books with anthropomorphic animals, the most famous of which, of course, is Shrek!

In Steig’s 1990 original narrative of the green ogre, Shrek, which yes, is Yiddish for “terror,” is a fire-breathing monster who relishes in scaring the public with his grotesque features. Booted from his parents’ house when he came “of age” (methinks this is not a reference to his bar mitzvah, as much as I want it to be), Shrek pays a witch rare lice in exchange for a fortune reading. Kicking off with the magic word “apple strudel” (is your Jewdar sounding off yet?) Shrek is told that, along with a donkey, he’ll voyage to a castle to marry a princess even uglier than himself.

After battling a dragon, the weather — he swallows a whole ass lightning bolt — and a disturbing dream in which he’s smothered with affection by kinderlach (children), the ogre bumps into the aforementioned donkey who leads him to the Nutty Knight of Crazy Castle. Yada, yada, yada, the dynamic duo enter the castle, chaos ensues, and Shrek lives “horribly ever after” with his princess, “scaring the socks of all who fell afoul of them.” Aw!

Jewish representation suffered a loss when the producers of Shrek discarded a scene suggested by then 90-something-year-old Steig to portray Shrek’s mom as “worrying about [Shrek], like a Jewish mother.” In all fairness, aside from a Yiddish name, the strudel, and his shofar-esque ears, there’s nothing explicitly Jewish about Steig’s Shrek. Scratch and sniff below the surface, though, and it’s obvious the story is drenched in Judaism.

In both versions of the iconic ogre, Shrek is an outcast who enjoys marching to the beat of his own mud bath farts. As a child of Polish Jews who fled Old World anti-Semitism, Steig’s monstrous creation is an extension of his experiences as a Jewish man and an allegory for the Eastern European Jew. “Shrek is an anti-hero, and Steig always said that the perfect hero is a flawed hero,” Claudia Nahson, curator of the Jewish Museum’s 2008 exhibit “From The New Yorker to Shrek: The Art of William Steig,” told the Seattle Times.

A total introvert, the Shrek of the movie genuinely enjoys the solitude of his swamp. After a hard day’s work of talking to no one, the territorial ogre wines and dines himself, even lighting a candle pulled from his ears (alas, a second candle would’ve screamed Shabbat). As the DreamWorks’ story goes, Shrek’s life got flipped, turned upside down when his quiet life is disrupted by a gaggle of fairytale creatures exiled from their kingdom by Lord “Douchebag” Farquaad.

Sound familiar? Shrek’s swamp is basically a fantastical shtetl in the Pale of Settlement, the region the Russian Empire “allowed” Jews to live in from 1791 to 1917.

Next on my Shrek-is-Jewish-agenda: Donkey. It’s about to get biblical here, so stay with me. In the Book of Numbers (Bamidbar 22:22-34) there’s a story about Balaam, a two-timing prophet who voyages on a talking donkey to aid King Balak of Moab. Is it a stretch to connect Eddie Murphy’s Donkey to a tall Torah tale? This adorable cartoon by Asher Schwartz doesn’t think so. After shaking off a gaggle of knights sent by Lord Farquaad, Donkey introduces himself to Shrek who is wholly unimpressed by the talking animal’s goofy antics. Begrudgingly, the ogre allows the asylum seeker to spend the night outside his swamp, because helping strangers is one of the 613 mitzvot. Shrek the ogre? More like Shrek the mensch!

Later in Shrek, the movie, the dynamic duo are faced with crossing a narrow bridge above a pool of lava to reach Princess Fiona, Shrek’s bride-to-be. Scared of melting to death from an accidental fall, Donkey totally freaks out, but with Shrek’s emotional support — “We’ll just tackle this thing together, one little baby step at a time” — he reaches the other side of the bridge safe and sound. There’s a Hebrew song I used to sing in grade school that reminds me of this scene. Written by the great Rebbe Nahman of Bratzlav (can I get a Rebbe-themed Bratz doll, please??), the lyrics in “Kol Ha’Olam Kulo” encapsulate Shrek’s fearless disposition: “The whole world is a narrow bridge, and the essential thing is not to fear at all.” The writers’ room might not have intended to create an overtly Jewish scene, but Shrek and Donkey literally crossed a “very narrow bridge” and that’s that on that.

It’s possible my connections are a little far-fetched, but Shrek 2 was written with Jewish wisdom and I have the receipts to prove it. In the sequel, Fiona’s father convinces Shrek that his daughter belongs in a palace as a royal, not in a swamp as an ogress. Totally gaslighted, Shrek decides the best way to support the love of his life is to let her go. (Spoiler alert: After turning into humans, Shrek and Fiona let the Happily Ever After potion ware off to continue living their best life as mudbathing ogres.) While tweaking the theme of the movie — “marriage is hard” — Jewish screenwriter David N. Weiss (who worked on A Rugrats Chanukah!!) recalled something his rabbi told him about love:

“Love means what’s important to you, is important to me,” Weiss told the JC. “This is incredibly hard for a man, because it means whatever your wife is talking about, even if it is trivial, it’s important to her, and if you love her, it’s important to you.”

Weiss, who was raised Jewish, converted to Christinianity, and now lives as an Orthodox Jew, said that the mostly Jewish writers’ room didn’t “say let’s make that the theme,” but “if you look at Shrek 2, I feel that it informs everything Shrek does.”

The rest of the Shrek franchise is filled with pearls of Jewish wisdom, I’m sure — even Jewish actor Nigel Lindsay said, “Shrek is going to be Jewish” when he played the titular role on the British stage. I don’t know if Shrek is circumcised (or if he even has genitalia), and he probably didn’t have a bar mitzvah. But religious rituals do not deem a creature’s Jewishness — it’s in their neshama, the soul.

Steig gave his ogre the unshakeable Jewish quality of being the misfit everyone loves to hate. In the book, there’s a bit where the ogre scares his socks off from glancing at his reflection in a hall of mirrors. After realizing it was just his grotesque figure, and not the evil king’s henchmen, Shrek is “full of rabid self-esteem, happier than ever to be exactly who he was.” Beyond the Jewish author, the shofar-ears, and his Yiddish name, self-love in the face of adversity is the most convincing argument for Shrek’s Jewishness.

If you’re still not convinced, look to the most credible source out there, Jew or Not Jew, for the official verdict:

“Remove the [Scotting] twang: you are left with a big-nosed misanthrope who is forced to live outside the Pale of Settlement, is not welcomed by the royals, and is subject to countless fiery pogroms…. Verdict: Borderline Jew.”

So there you have it. And oh, if you’re wondering what Steig thought of the movie adaption of his most famous work, he once said: “It’s vulgar. It’s disgusting — and I love it!”