Most likely any conversation around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will include the words Zionism or Zionist. But what do these words actually mean, and how have they changed over time? Let’s break it down.

What is Zionism?

The definition of Zionism has evolved over time: There’s pre-1948 Zionism and post-1948 Zionism (not to be confused with post-Zionism, another idea altogether).

Post-1948 Zionism — arguably what most people consider the definition of Zionism today — can be simply defined as the belief that the State of Israel has a right to exist, that Jews have the right to self-determination. (This definition is up for debate, though.)

Pre-1948 Zionism is a little bit more complex. To sum, it was the general movement to establish a Jewish state. The modern state of Israel is therefore the culmination of Zionism, the Jewish effort to establish an autonomous state and end the diaspora of the Jewish people. Political Zionism was a product of many trends: the persecution of Jews in Europe and Arab lands; the rise of nationalism around the world; idealistic visions for building a new kind of society; and the conclusion that Jews would only be safe if they controlled their own destinies, to name a few.

Back up: What’s the diaspora?

The Jewish diaspora, also called the galut (exile), is the dispersion of Israelites/Jews out of their ancestral homeland. Jews typically trace their status as a nation to the Kingdom of Israel — you know, the land ruled by King Saul, King David, and King Solomon from the Bible — around 900 BCE.

The historical record shows Jewish kingdoms in various forms in what is present-day Israel from then through the era of Roman rule that began in about 60 BCE.

The Jewish exile is commonly dated from the Roman destruction of the second Temple in 70 C.E. Since the exile, there has been a Jewish longing to return to the “promised” land as God gave to Abraham and his descendants in Genesis 15:18 and Genesis 17:8, and where the Jewish Temples marked the center of Jewish religious and political life.

During the exile, a significant part of Jewish prayer and scripture focused on the Jewish desire to return. For example, Psalm 137:1, 4-5 is super famous (you may recognize the reggae song): “By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept, when we remembered Zion… How shall we sing the song of the Lord on foreign soil? If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand wither!”

Ok, so is Zionism a religious thing?

Short answer: Not really. Zionism, as we think of it today, was a largely secular, nationalist movement that used Jewish religious symbols. Zion is essentially a synonym for Jerusalem.

Long answer: There are a lot of different types of Zionism and Zionists. Zionism wasn’t just one movement. Some of these were religious, and some weren’t.

Let’s break down the different types of Zionism. It’s important to note that these aren’t mutually exclusive — people can belong to multiple Zionist camps at the same time.

The different types of Zionism

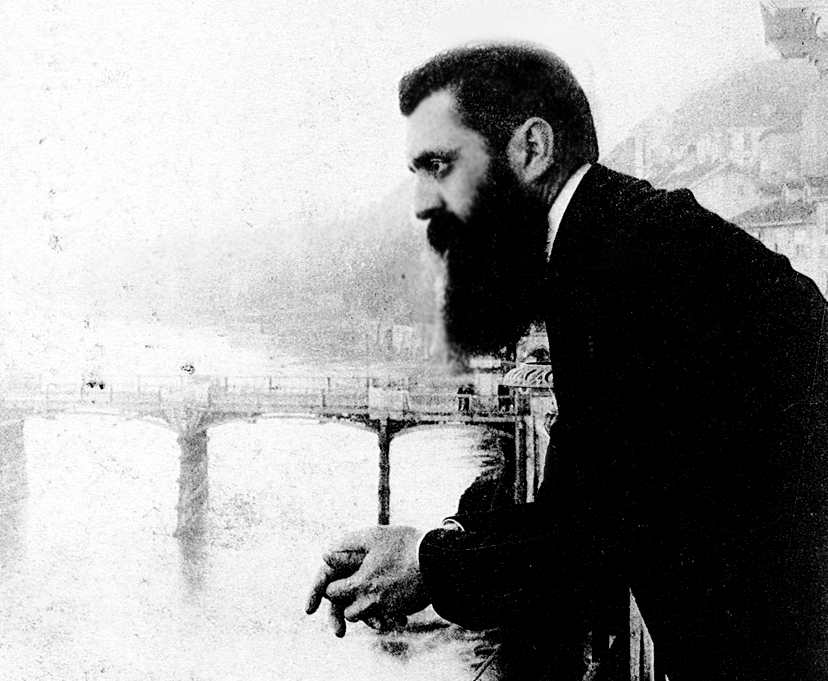

POLITICAL ZIONISM

This is probably what you think of when you think of Zionism. This was a largely secular movement that grew out of 19th century European nationalism and basically said Jews are like any other national group and — especially given the persistence of anti-Semitism — deserve and need a state of their own.

CULTURAL ZIONISM

A movement associated with the writer Ahad Ha’am (Hebrew for “one of the people”) and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the most important figure behind the revival of modern Hebrew, cultural Zionists wanted to ensure the Jewish state was not just a state that happened to be populated by Jews, but one with a vibrant Jewish culture.

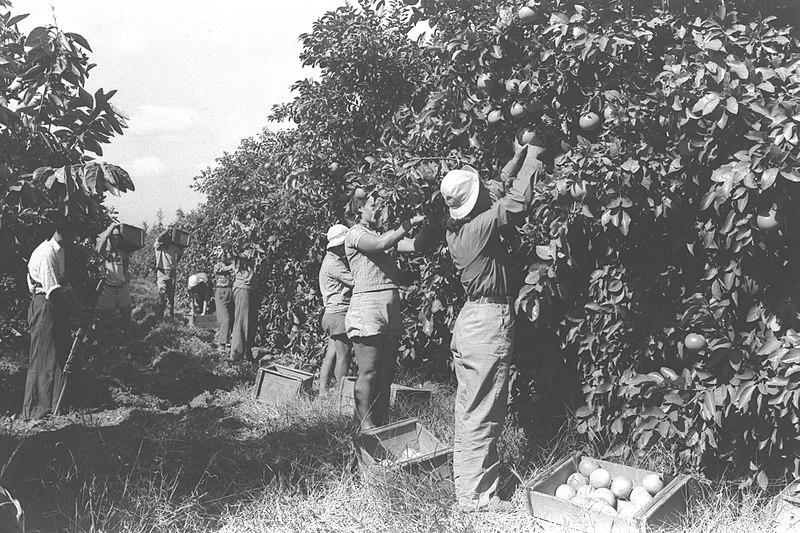

LABOR ZIONISM

This was the movement behind the establishment of the kibbutzim, the collectivist farms instrumental in Israel’s early history. Labor Zionism emphasized the transformative power of the land and shaped the early leaders of the Jewish state. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, was a Labor Zionist.

REVISIONIST ZIONISM

This was a militant splinter movement led by Ze’ev Jabotinsky which split from the larger Zionism movement in the 1920s and wanted to achieve a Jewish state more quickly and aggressively than the Labor Zionists.

RELIGIOUS ZIONISM

Religious Zionists believe that the establishment of the state of Israel is part of the divine plan for redemption. Unlike some religious Jews, who think that restoring Jewish sovereignty in Israel has to wait until the coming of the messiah, religious Zionists consider settlements in Israel and army service to be holy acts.

CHRISTIAN ZIONISM

This is basically what it sounds like. Christians who support Jewish sovereignty in Israel do so mainly because they believe the Jewish return to the holy land is a precursor to the second coming of Jesus, and because they take seriously the biblical verse, “Whoever blesses Israel will be blessed, And whoever curses Israel will be cursed.” (Numbers 24:9)

Whew! Still with us?

Yep.

Let’s (briefly) talk about anti-Zionism

As Zionists began to settle what was then part of the Ottoman Empire in the 1880s — and picked up the pace in waves before and after World War I — what was at first scattered resistance from the Arabs who then made up the majority of the region’s inhabitants became more and more intense.

After the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, a move sanctioned by the United Nations, many countries (such as Egypt, Syria, Jordan, etc.) refused to acknowledge the Jewish state and instead called Israel the “Zionist entity” or “illegal Zionist entity.” Critics call Zionism a colonial-imperialist movement, a racist movement, and more, which Zionists categorically deny. But this is a really messy subject and can veer into rancor and anti-Semitism, so we’re going to save this for another article… (See: is anti-Zionism always anti-Semitism?)

Israel’s already a state, so is Zionism still a thing?

Good question. What does Zionism look like after the establishment of Israel? Weren’t the goals of the Zionist movement just, like, met?

Zionism remains as a philosophy that views Israel as a homeland for all the Jews, one that was proven necessary by Israel’s role in taking in Holocaust survivors, Jews who fled persecution in the Soviet Union, Jews expelled from Arab countries, and Ethiopian Jews.

And while the state is a reality, contrasting visions of what Zionism means leads Israelis to hold vastly different ideas on how Israel should be governed, what role religion should play, how it treats its non-Jewish citizens, its relationship with Palestinians (and with Arab nations), and so forth… (See: how do Israeli politics work?)

What is Post-Zionism?

Post-Zionism is, broadly, a critique of Zionism and the state of Israel that tends to come from within. In its least controversial form, it says that Israel is now a reality, and it should focus on the practical aspects of being a “normal” nation for all of its citizens. A more radical form of post-Zionism calls into question the very foundations of Zionism. The moderates and radicals usually come back to the same set of questions: Is it possible to have a state that is both Jewish and democratic? Is Israel really the safest place for the Jews? Do Jews have to be in Israel?

Post-Zionism, as My Jewish Learning explains, is “indicative of an increasing sense among many Israelis that the maps of meaning provided by Zionism are simply no longer adequate.”

What does it mean to be a Zionist today?

It means a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

For many, it means they believe in the right of the Jews to self-determination. Nothing more, nothing less. It means they believe Israel should exist.

For many Jews living outside of Israel, Zionism describes their commitment to supporting Israel — politically, economically, and spiritually.

For many of Israel’s critics, Zionism is a flawed and even illegitimate notion, which means Israel is itself considered illegitimate. Many of them equate Zionism to “the ideological, ultra-nationalist settlers and their supporters in the Likud-led government.” (See: UN Resolution 3379.)

Others believe Zionism ended on May 14, 1948, when the State of Israel was established. As writer Anshel Pfeffer opines in Haaretz, “Despite the -ism in its name, Zionism was never an ideology, it was a program. For the 66 years of its existence there were heated debates over Zionism’s justification, objectives and the best means for achieving them. They ended on May 14, 1948, when an independent Jewish state was established on part of the ancient homeland.” Basically: Arguing over Israeli policies today does nothing to change how Israel came into existence, nor the Zionist movement that brought it there.

So, you know, no simple answers here.

2014 Israel-Gaza conflict

Known to Israelis as Operation Protective Edge, this was a military campaign launched by Israel in 2014 in response to the kidnapping and murder of three Jewish teenagers by Hamas.

jihad

Jihad is an Arabic word meaning “struggle” that can refer both to holy war against nonbelievers and personal moral struggle.

Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas is the current head of the Palestinian Authority and chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Fatah

Fatah is the political party of Yasser Arafat.

Black September

Black September refers both to a conflict fought between Jordan and the Palestine Liberation Organization and to the terrorist group that carried out the massacre of 11 Israeli atheletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972.

PLO

The Palestine Liberation Organization was a group founded in 1948 to liberate Palestinian territories through force. Israel considered the PLO a terrorist group prior to the 1994 Oslo Accords.

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces, commonly referred to as the IDF, is Israel’s military.

Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian Authority is a Palestinian governing body established for the purposes of Palestinian self-government by the 1994 Oslo Accords.

Temple Mount

The Temple Mount is a site in the Old City of Jerusalem considered the holiest place in the world by Jews and the third-holiest by Muslims.

Green Line

The Green Line refers to the armistice line that separated Arab and Israeli forces at the conclusion of the 1948 war. Sometimes referred to as the 1967 border, it is considered by many the basis for negotiating a final border between Israel and a future Palestinian state.

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion was the first prime minister of the State of Israel.