For a book set in the near-future, Adam Wilson’s “Sensation Machines” feels pretty damn current. Social upheaval, antisemitism and class wars swirl in the background of the high-intensity novel that follows Jewish couple Wendy and Michael Mixner, the latter of whom is a Wall Street trader who’s hiding the fact that he’s lost all of his money from his wife. Wendy is working on a top-secret campaign for an eccentric millionaire game developer Lucas Van Lewig who believes he has the perfect solution to the unemployment crisis ravaging the country. Meanwhile, they both are still struggling with the trauma of stillbirth and the murder of their friend.

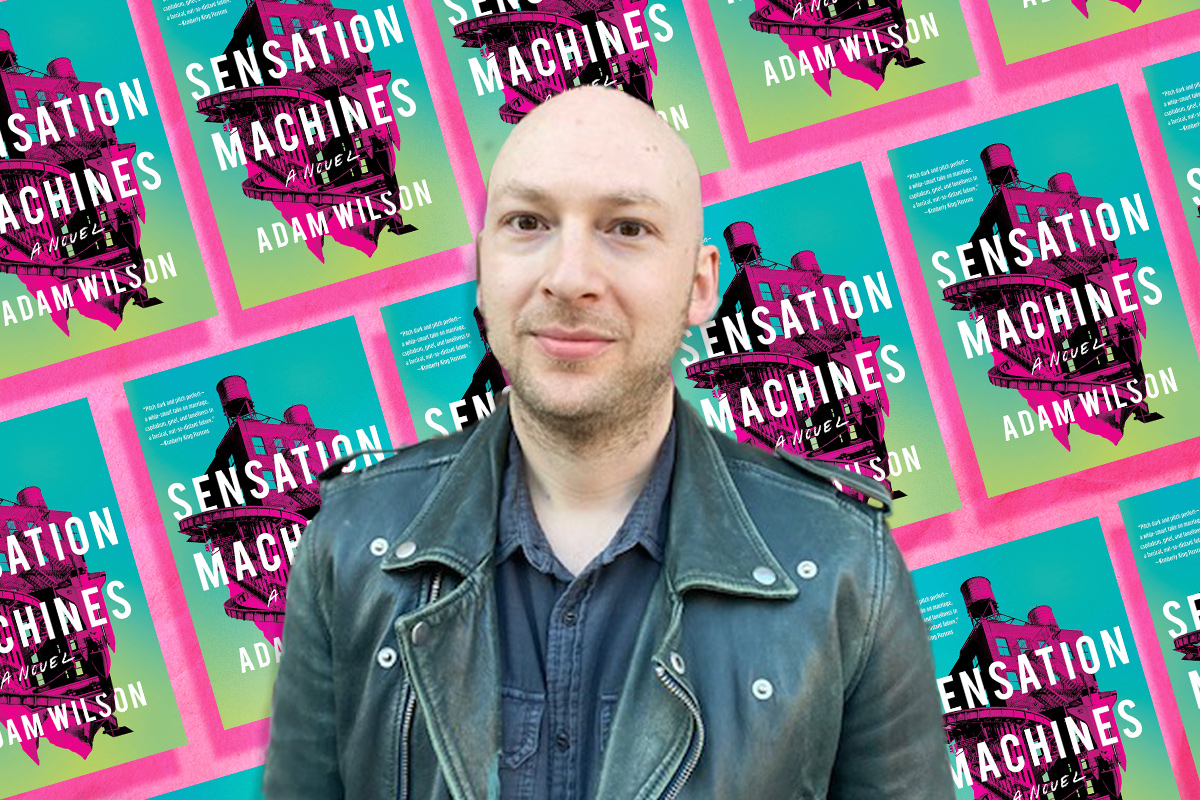

Wilson, whose previous books include “Flatscreen” and “What’s Important Is Feeling,” offers his sharp wit, biting commentary and distinctive Jewish lens on American society and capitalism in this page-turner that’s equal parts terrifying and funny. Originally released last July to a world ravaged by a global pandemic, the paperback is out this week. I had the pleasure of chatting with Wilson over e-mail about the real-world events that inspired some of the plot, his characters’ bar mitzvahs, and the trickiness of writing about Jews and money.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Your book was first published last July, when there was… kind of a lot going on. What did it feel like to release the book into that climate? And how does it feel now, when things are different, but also, maybe not?

Since I’m speaking to an audience of fellow Jews, I won’t sugarcoat it as I might to my kvetch-averse (read: gentile) in-laws: It was terrible! Aside from the obvious challenges of marketing and promotion, I was so disappointed that I couldn’t do in-person events. Writing a book is such a solitary pursuit, and in my experience, one of the joys of publishing one is finally being about to share it in public. I did some really nice Zoom events, but it’s just not the same. As you say, things aren’t great now either, but I’m looking forward to at least being able to see the book in a bookstore (finally!) and do some (masked, vaccinated) in-person readings.

I couldn’t help but notice the many references to your Jewish characters’ bar/bat mitzvahs throughout the book. Even Lucas Van Lewig, decidedly not a Jew, references a time when he was 12 years old and his father taught him how to fight, calling it his “Anglo-Saxon bar mitzvah.” What drew you to the concept of bar mitzvahs as a motif throughout the book? Did you have a bar mitzvah?

That’s interesting that you noticed that. It’s not something I was aware of until you pointed it out, but obviously somewhere in my unconscious I was stuck on the idea of bar and bat mitzvahs. I guess it makes sense because, having grown up in a predominantly Jewish suburb of Massachusetts, I spent a lot of time attending them, at least between the ages of 12 and 14.

I don’t think I’ve ever actually written a bar mitzvah scene into a novel or story, but I do think of them as events with great comic potential. The cruel absurdity of making a pubescent teenager sing in an unfamiliar language in public just as their voice is breaking will never cease to amuse me! And then there are the parties, which can be like these tacky, themed mini-weddings. I’ve always been interested in what strikes me as a very American intersection between religion and materialism, the idea that this ancient, sacred ritual can be so closely linked to these gaudy displays of wealth.

My favorite bar mitzvah scene in literature would have to be from Sam Lipsyte’s story “I’m Slavering,” in which a character cuts off his own thumb before his bar mitzvah, then serves it to his parents on an olive dish, a kind of metaphorical auto-circumcision. Nothing quite so dramatic happened at my own bar mitzvah, though the event was not completely without scandal. My haftarah was Ezekiel 1 — Ezekiel’s vision of the divine chariot — and in my bar mitzvah speech I talked about The Beatles and LSD, comparing the prophet’s vision to “Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds.” It seems insane to me now that anyone allowed this to happen, least of all my parents, but I guess it was the ’90s. The real shonda, however, was that I decided to style myself in a rather fashion forward collarless dress shirt, and thus became the first bar mitzvah boy in the history of my Conservative synagogue to not wear a tie. It caused quite a stir!

Wendy and Michael are very wealthy (or were very wealthy until the market crashed). They are also Jewish. Obviously, Jews and money can be tricky territory — antisemitic tropes abound, but there is also a real subset of American Jews that are financially privileged. How much of that was in your head while writing the book?

One thing I was very consciously trying to do in the novel was represent Jewish American characters across a broad spectrum of class. Some people think of American Jewry as monolithic — politically, economically — but it’s not; there are all kinds of Jews in this country. And yes, as you say, a segment of them are financially privileged, but even among that segment, there are seemingly endless micro-delineations of class and social strata.

In my previous novel, “Flatscreen,” the narrator describes his family as “lower-upper-middle class,” which was meant to sound both absurdly specific and totally vague. What does being financially privileged actually mean? Well, different things to different people. For the Jewish characters in “Sensation Machines” — as well as, I think, for many American Jewish families whose wealth is relatively new, at least compared to, like, descendants of The Mayflower — it’s a precarious condition, one that at least feels like it’s in perpetual danger of slipping away. So I wanted to explore all that in the book, to try to capture that nuance in a way that I hope offers an alternative to some of the more reductive misconceptions about Jews and money.

One of the most horrifying concepts in the book is a campaign Wendy’s working on called “#workwillsetyoufree,” the German phrase that appeared at the gates of Auschwitz (sans hashtag). She is probably sadly accurate in her feelings that most people won’t get the reference. Were you trying to make a statement about the lack of Holocaust education — or lack of an understanding of history in general — with this idea?

It’s funny, when I first turned the book in to my agent, she was concerned that it wasn’t believable that people in the novel wouldn’t get the reference. But about a week later a study came out saying that two thirds of Millennials have never heard of Auschwitz. And that was a few years ago — I can only imagine what it’s like with Gen. Z!

There’s also a minor subplot of a hostage situation at the FSU Hillel. Were you thinking of recent antisemitic events when including that?

Yes, in the novel a group of Zionist Nazis take hostages at a Hillel. This was intended to be a joke about how the American right seems somehow able to both love Israel and hate Jews. But like a lot of things in the book, it’s also not really a joke at all; it’s a warning, because I totally believe something like this is possible. Slight digression, but my wife and I just watched HBO’s six-part Q-Anon documentary, and man, those people are terrifying.

The book takes place in the not-so-distant future, when most minimum wage jobs are replaced by robots, it’s normal for people to wear virtual reality helmets wherever they go, and a major push for Universal Basic Income is afoot. Come to think of it, all of this exists in one form or another now. What are the aspects of our ever-nearing future you’re most afraid of? Most excited about?

Honestly, I’m finding it very hard to imagine what the future will look like. A couple months ago I thought I no longer had to worry about COVID, and now I’m up half the night worrying about COVID. And then there’s Afghanistan, and climate change… and now I need an Ativan. I guess what I’m most excited about is that despite this dystopian nightmare, my wife and I will be welcoming our second child into the world this fall, so a least that’s one thing I can say I’m looking forward to.

Despite all the heavy topics explored in “Sensation Machines,” it’s also incredibly funny (I personally cannot stop thinking about Wendy’s slogan for McDonald’s in India, “Eat, Pray, Loving It”). How do you balance writing humor with more serious topics like capitalism, justice, and even pregnancy loss?

My natural instinct as a writer is comedic, so for me the biggest challenge is knowing when to reel the humor back in so it doesn’t undercut the seriousness of the larger issues I’m attempting to explore. At the same time, I feel like being funny allows me to get into some of that more serious stuff — finance, say — by taking what might seem like an inherently dull topic and surrounding it with jokes.

Who’s in your Jewish writer canon?

My father, who is also a writer, has written about and taught the works of Saul Bellow and Philip Roth for going on 40 years now. I’m a fan of both, but when I was starting out, it felt imperative that I find my own, alternate models for what a Jewish writer could be. For this reason, I tend to be drawn to the slightly less famous Jewish writers, the ones who never quite got their due.

It’s probably much more apparent in my short fiction than in “Sensation Machines,” but Grace Paley has been a HUGE influence on me, both as a writer and a person. Her stories are the benchmark, as far as I’m concerned. Leonard Michaels is another really important writer to me, especially his first two collections of stories. Iris Owens’ “After Claude” and Elaine Kraf’s “The Princess of 72nd Street“ are two of the funniest Jewish novels ever written, and aren’t read nearly as much as they should be. But there are so many others: Stanley Elkin, Mordechai Richler, Max Apple. I love Leonard Cohen’s fiction, especially his under-read first novel, “The Favourite Game,” which reads a bit like a Canadian “Portnoy’s Complaint.” Fran Ross’s “Oreo” is another semi-obscure favorite. E.L. Doctorow’s less obscure “The Book of Daniel” is another. And of course there are the Russians, particularly Isaac Babel and Osip Mandelstam, and some Israeli writers such as the great lost Modernist novelist Yaakov Shabtai, and his living brother, the wonderful poet Aharon Shabtai. The Italian writer Italo Svevo has also been very important to me; he’s half-Jewish, but his novel “Zeno’s Conscience” is undoubtedly the best novel ever written about hypochondria, which is perhaps the most Jewish of all topics. Among contemporary writers, I’m so indebted to Sam Lipsyte as both a literary influence and personal mentor that I’ve taken to referring to “Flatscreen” as Sam Lipsyte fan-fic. Binnie Kirshenbaum, too, has been a huge influence both as a writer and a teacher — she’s easily one of the funniest living Jewish writers. And I’m lucky to have so many amazing Jewish writers as friends and peers: Justin Taylor, Robin Wasserman, Rebecca Schiff, Rachel B. Glaser, Joshua Cohen, Elisa Albert, Molly Antopol… I could keep going!