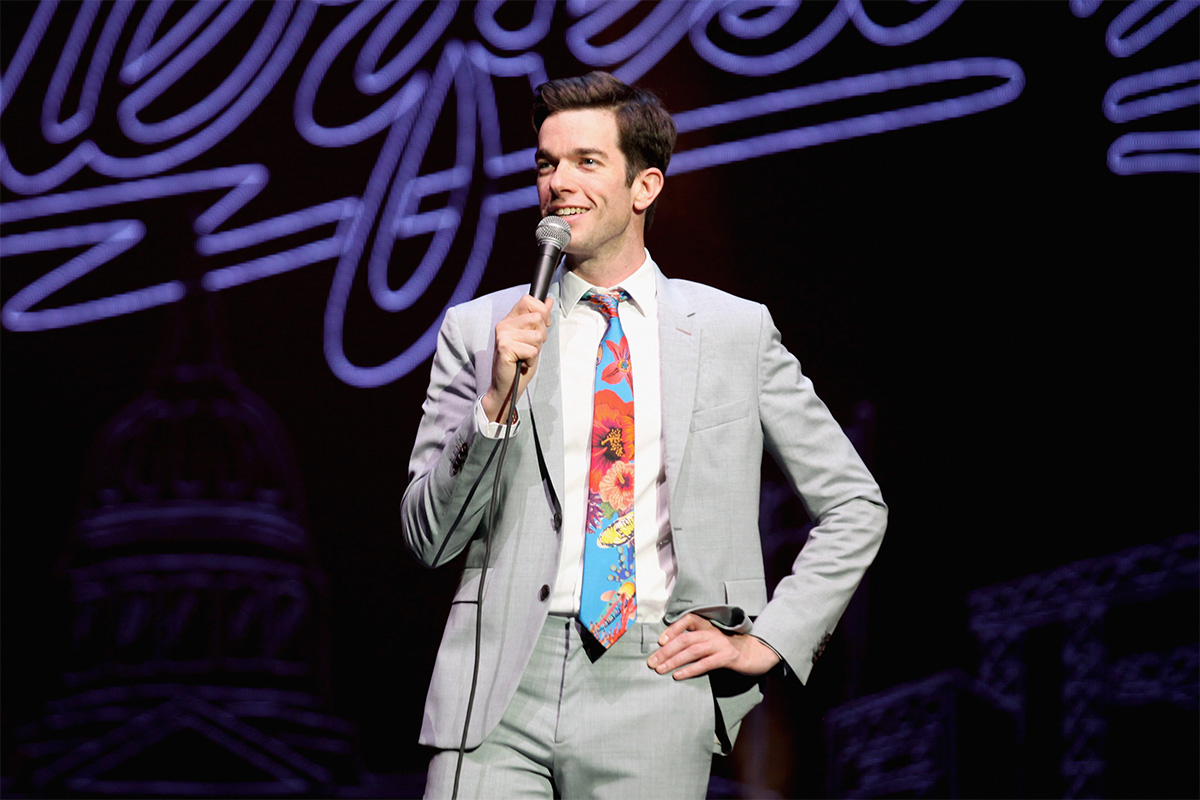

When news circulated that the comedian John Mulaney was divorcing Anna Marie Tendler, coupling with Olivia Munn and having a baby, I — along with many millennials — was shocked. What happened?

You have to understand, this was neither an ordinary celebrity break-up nor a logical next step for a newly minted celebrity couple. In every stand-up routine, Mulaney had gushed over his now ex-wife, marveling over her confidence and honesty. And for many of us, these moments were pure gold, a peek into a thoroughly millennial relationship — interfaith (Mulaney is Catholic and Tendler is Jewish) and childless (Mulaney had always been clear that the two did not want children). It seemed Mulaney and his wife were joyfully, gleefully making a life for themselves based on their own terms.

Since last spring, many think pieces have come out unpacking why the Mulaney-Tendler-Munn drama hit fans so hard, and almost all of them cite Mulaney’s brand of humor as cause. Mulaney’s humor is wholly autobiographical, and so we felt that we knew him because we watched his stand-up. But as several people (including my husband) have pointed out, we really do not know the real John Mulaney — we just know the comedic persona he has crafted. Most of his audience simply took this crafted persona for the real thing.

A year later, the sting has worn off, and as I was cleaning my home one day, I decided to re-watch “Kid Gorgeous,” Mulaney’s Netflix stand-up special from 2018. About halfway through, Mulaney began to extoll the many virtues of his ex-wife and I stood still: “She is a dynamite, five-foot, Jewish bitch and she’s the best.” Post-divorce, the words left a strange reverberation in my ear. I started watching stand-up after stand-up, and it hit me over and over again: Mulaney wasn’t just infatuated with his wife; he was infatuated with his wife’s Jewishness.

Being a secular Jewish woman is difficult. Growing up, I felt like I had to toggle between two worlds: the Jewish one where I never fit in (I was never the one to lead the Hanukkah assembly or attend Jewish summer camp) and the secular one where I often felt that I was playing defense against the Jewish stereotypes floating about in ‘90s pop culture — the Jewish American Princess, the Jewish mother-in-law, and the loud and bossy Jewish woman.

When I was in my early 30s, I found myself in an interfaith relationship with a man who would soon become my husband, and back then, hearing John Mulaney, a non-Jew, lovingly celebrate his wife for all of the stereotypes I had avoided gave me pause. Maybe there were people out there (besides my boyfriend) who admired my tendency to be bossy, opinionated and blunt. Maybe there were people out there who appreciated my ability to find a good sale and easily slip into a bona fide Jewish Brooklyn accent. Mulaney’s joy in his then-Jewish wife freed me to enjoy all of the Jewish parts of my identity I had guarded.

But this time as I watched Mulaney, something did not feel right. Emphasizing that his now-ex-wife is a short, bossy, Jewish bitch unnerved me. It didn’t feel like a celebration, but more like an exoticization. Mulaney was marking Tendler as an other. Why couldn’t Anna Marie Tendler just be short and bossy? Why did her height and habit of saying exactly what she was thinking have to be tied to the fact that she — in whatever way that she does — identifies as a Jew? I kept asking myself, “Are only Jewish women loud and bossy? And is every Jewish woman like this?”

The more I think about it, the more I find that Mulaney’s celebration of Anna Marie Tendler reads as a form of toxic masculinity, one in which white cis Christian men prevent others from entering mainstream culture. For decades, Jewish women and men have tried to hide and mask various Jewish cultural trappings in an effort to pass in a country ruled by a non-Jewish majority.

Of course, things have vastly improved, and we see it in pop culture. TV shows like “The Goldbergs” and “Schitt’s Creek” celebrate modern Jewish families, Larry David is a cultural icon, and more and more, the diversity of American Jewry is emphasized and celebrated.

But the fact still stands that we Jews, for better or worse, are not your everyday “traditional” Americans — and that’s absolutely fine. What’s not fine is when people like Mulaney, enrobed in a false mantle of celebration, use their position of power to further other us. His comments prevent Tendler and Jewish women like her from fully entering into mainstream Americana. It’s a very effective way of keeping certain people out of what is considered “normal” and “acceptable” in America.

And no, I do not find it funny.