When I call up Jordan Salama, he has just finished a cross-country train trip from New York to California. It’s his first time in the Golden State and he has woken up early to take a beginner’s class in Baghdadi Judeo-Arabic, the Jewish Arabic dialect of Baghdad his mom’s family speaks.

“I’ve been on this mission to learn Arabic for the last year and a half,” Salama tells me as he walks through San Francisco early in the morning. “But it’s really hard, because what dialect do I learn? My family doesn’t even speak the regular Muslim dialects. The professor said, ‘welcome to the first class of beginner’s Judeo-Baghdadi Arabic maybe ever.'” The class is part of 12 new courses in rare Jewish languages offered by the Oxford School of Rare Jewish Languages.

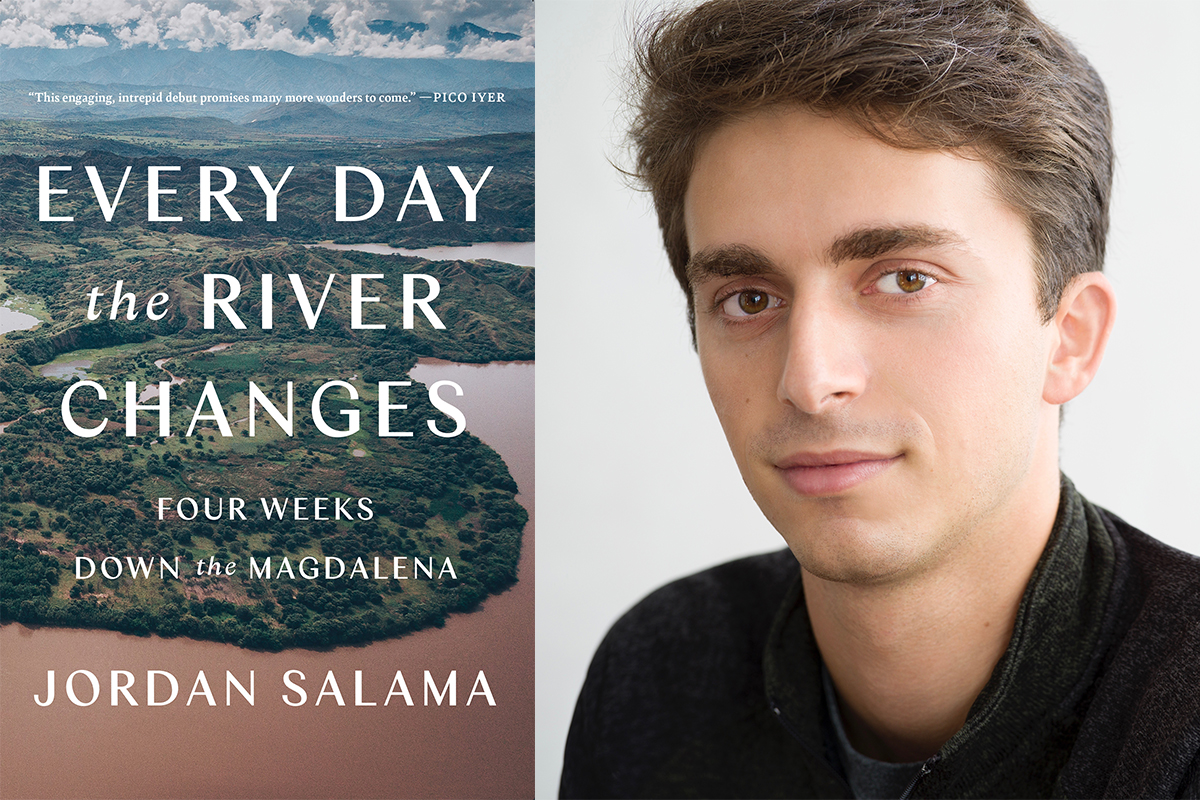

But we’ll get to his family later, because first, we have to discuss his debut book. “Every Day the River Changes: Four Weeks Down the Magdalena” is a travelogue of the Jewish writer journeying down Colombia’s Magdalena River, a nearly thousand-mile river running through the heart of the Latin American country.

Salama, the son of a Syrian Argentinian Jewish father and an Iraqi Jewish mother, writes about never feeling truly at home in the United States, and about how traveling feels inherently Jewish to him. Salama’s journey — which he undertook as a senior in college, no big deal — takes him from the Magdalena’s source in the Andes to its mouth on the Caribbean coast. He travels by boat, bus and more to traverse the nearly 1,000 miles.

I talked to Salama about the Jewish tradition of trading stories, how he hopes travel will look in the future, and where he hopes to go next.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

As a travel writer, whenever you’re going someplace new, are you always thinking about it through the lens of “how am I going to write about this”? Or do you let yourself take it in, and then those questions come in later?

It depends on my outlook on what I might want to write about, or how my interests fit in with a place. If I’m going to a place with a socio-political context at front of mind, I have to be thinking about those things when I’m engaging with the place. But if it’s something like taking the train across the country — which is just purely a really wonderful adventure — I do it because I’m interested in it. I also know it’s fodder for future stories.

Yeah, I feel like as a Jewish culture writer, whenever I’m watching or reading something and there’s a Jewish reference, I’m like, “shit, now I gotta write about this.”

It’s a very true problem for any writer who writes about things that are close to them. There’s a story by Jorge Luis Borges called “Borges y yo,” Borges and I. It’s fiction, but it’s him talking about his writer persona and his person persona, and how his person persona has essentially begun living his life in order to serve the writer Borges, the famous Borges. And he grapples with that, and he much prefers to be the Borges Borges, but inevitably the two are just conflated — the story talks about what that does to his life. Obviously not a problem that either of us has to deal with, but it’s relevant for all writers who don’t just report news that has nothing to do with them.

When you did your trip down the Magdalena River, was there anything you wish you had done differently when you were traveling and taking it all in?

“Every Day the River Changes” is very much the story of one young person journeying down a river; I don’t think it tries to be super comprehensive or an all-encompassing story of Colombia. This is very much a journey that tries to illuminate aspects of everyday life. It being that kind of journey, I don’t think that you can necessarily wish or hope that you would go back and do anything differently in the travels — because everything that happened, every person who I met, inevitably influenced who I would meet next.

I also really love what you wrote about trading in stories — how everyone you met opened a door to a different story.

Trading stories is a very Jewish thing for me. I come from a family of traveling salespeople, wandering merchants who traded along the great two trade routes of the world: the Silk Road and the old Inca road in the Andes of Argentina. I grew up hearing the stories of people who sold textiles and items, and it dawned on me that though I may not be selling clothes, I very much am taking these journeys where I trade in cultures and stories and experiences and try to connect people through these trips in the same way. These ancestors maybe would have connected people through their trading, picking up little pieces of cultures, sharing them with the next people that they would meet — blending worlds and introducing people to other things. That was really the goal of this book, and I think it should be the goal of travel writing moving forward. There is so much that can be done in the genre that hasn’t been done in the past — connecting people, emphasizing empathy and cross-cultural understanding.

What was it like traveling as a Jewish person?

One of the first questions people would ask me was what my religion was. And what a tough question that is because, I mean, I’m not a particularly religious person. I wouldn’t say that I was Catholic, because that would be a lie, but it would expose me very quickly because a lot of them were very religious Catholics. I didn’t necessarily want to say that I was a Jew because we all know that can cause problems. And then I would usually just say, “I’m not very religious,” that would be the vague answer. And usually nobody questioned it. But in some cases, people didn’t like that, either.

You write of your family, “There seemed to be no port where their wanderings hadn’t reached, and no place where there wasn’t an adventure to be found.” Do you ever think of the idea, or the stereotype, of the wandering Jew?

The wandering nature of the Jewish people has caused really beautiful things. In America, people don’t realize that there are Jews in Latin America. There are Arabic-speaking Jews in Latin America, German-speaking Jews in Latin America, Russian-speaking Jews in Latin America. There are Iraqi Jews in India, Sephardic Jews in Burma! Because of these wanderings, forced or voluntary, for business or for persecution, there are these really special places of Judaism and [communities] of Jewish people.

That’s one thing that Alma does really well — you have a lot of articles about that, that’s one of the most valuable things. People in the US have a very narrow view of what it means to be Jewish and what Jewish people look like. The truth is, anybody can be Jewish, and you may not know it just from looking at somebody, or seeing their last name.

That’s our whole friggin’ motto here at Alma, so it’s good to hear you say that. And you’re the son of a Jewish dad who is Syrian Argentinian and a Jewish mom who is Iraqi. How do you understand your own Jewish identity?

Growing up in the suburbs of New York, a very Jewish place, I’ve always felt very different from all my friends who are Jewish. A common sentiment among Arab Jews is that you feel a large affinity towards the Arabic, Middle Eastern culture, but in many ways, there are traumatic memories of expulsion associated with that, too, passed down through generations. You feel very Jewish, but people see you as extremely different.

Over the years, my family members could tell you that both in Israel in the U.S., they were treated differently in Jewish circles because they were “Arab.” So it’s a weird place — you’re in the middle of these two identities, and you’re told in every way that they’re in conflict. Every time there’s something that flares up in Israel-Palestine, that is just heightened, because you hear about “the Arab Jewish conflict,” and you’re like, “Wait a second, I feel like I’m both.”

I guess this goes back to this idea of bridging cultures and identity. I’m so lucky to have been born in this weird mix of families and traditions while still being Jewish — it is a really special thing. If there’s one pure motivator for why I do this kind of work, it’s because of that, and the stories that come from that.

What’s your favorite Jewish family tradition?

I liked that on Passover, Iraqi Jews hit each other with green branches to celebrate the coming of spring. We call it “sintak khuddura,” or a green year. I’ll wake up in the morning to, like, my brother slapping me with a green stick on my bed, or my mom will run down the stairs and sneak up behind someone and start hitting them with a green stick. We’ve turned it into a fun thing.

Where would you want to travel next?

Front and center, if I can get the guts up to do something like this, is to go to Baghdad. I want to go to Baghdad and see where my family used to live and where my mom was born. Ideally, I would go with one of [my family members] who remembers, but that’s maybe harder, it might just be easier to go by myself. Iraq seems to be opening up, if ever so slightly, to travelers from foreign countries. There are some really, really amazing groups of young people who are trying to encourage [travel] in the country. I would love to support them in that. There’s a huge contingent of Muslim people in Iraq who are interested in the history of Iraqi Jews. As soon as I can figure out a way to do it, safely and in a way that I’m comfortable with, I will. That’s where I want to go.

What places would you want to visit in Baghdad?

My family owned and operated some of the first movie theaters in Iraq, and the first movie studio in Baghdad — they basically produced the first movie from the Iraqi cinema, that was produced and filmed in the country. And that was all done by Jews. The guy who wrote it was Jewish, Anwar Shaul. The people who made the music were [Iraqi-Kuwati Jewish musicians] the Al-Kuwalty brothers, who are very famous. And then my great-grandfather and his brothers were the producers. Those cinemas are still standing. I’d love to go there and talk to the caretakers — I’m sure they know so much history.

As I read your book, the COVID delta surge was happening, and I kept thinking, Wow, I can’t imagine taking this trip. In today’s world, it’s so escapist to read a travel book; travel looks very different, and how we interact with others feels so different. How does it feel to talk and think about this book in a world that is very different from the world in which you wrote it in?

I can’t imagine right now being able to do the same thing that I did then, which was essentially knocking on people’s doors and asking if I could stay in their houses. I stayed with families pretty much along the entire route, and that obviously had a huge impact on the stories that I was able to gather and share. I hope that people will read it and be able to have a little adventure from their armchairs.

Humans are migratory moving people, whether we want to move or not — travel will be back, whether we want it to or not. I hope that maybe, by reading this book, or by having this book, people will become better travelers — more sensitive, more empathetic travelers.