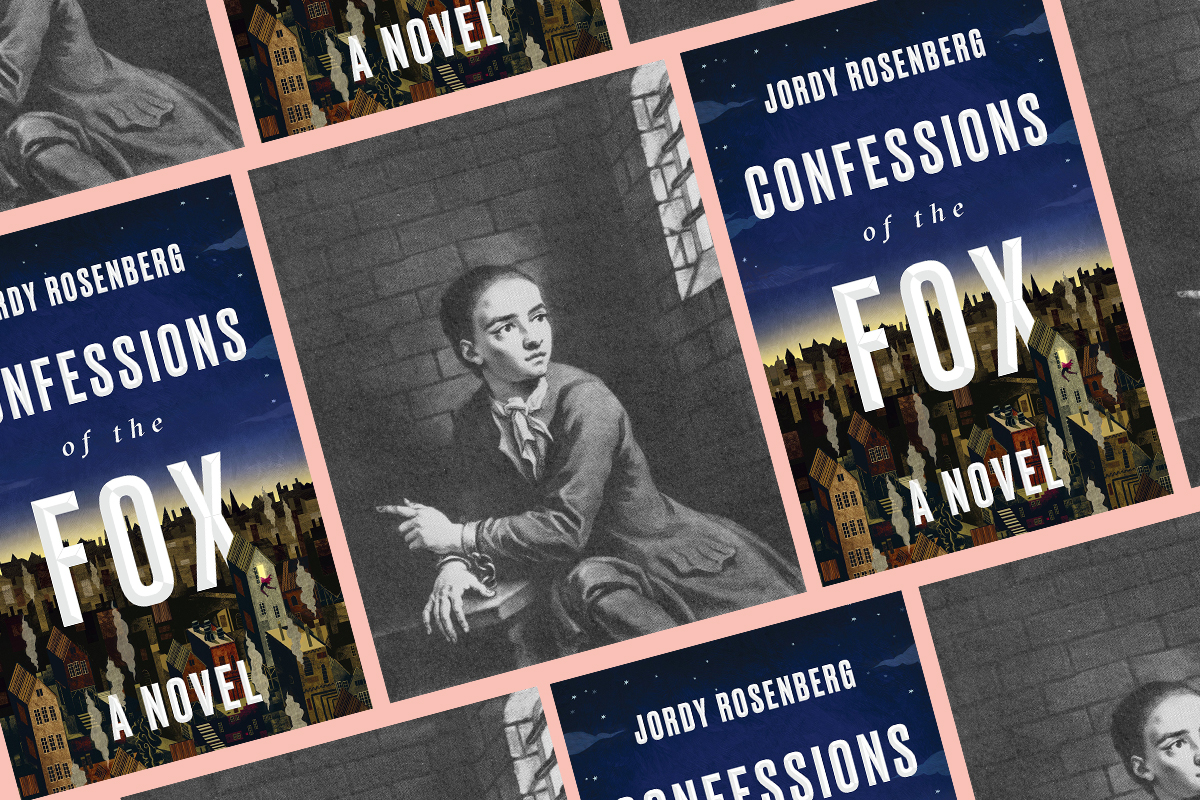

Jordy Rosenberg’s Confessions of the Fox begins with a note to the reader by its fictional narrator, Dr. R. Voth, who writes, “There are some things you can see only through tears.”

Filled to the brim with queer and trans theory, Rosenberg describes Confessions of the Fox as “Trans + anti-imperialist + anti-capitalist speculative fiction of jailbreaks and sex hormones.” As Eileen Myles explains on Twitter, the book is “so palpable and fantastic, dizzying and compulsively readable.”

Rosenberg’s debut novel is speculative metafiction; he takes a well-known historical figure and spins the narrative into something new. In Confessions of the Fox, Rosenberg writes Jack Sheppard — an English folk hero who really existed, who was an 18th-century English thief who escaped from the notorious Newgate Prison — as a trans man. In real life, Sheppard’s mom sent him to a workhouse when he was 6. In Rosenberg’s telling, Sheppard’s mom, confused by her daughter who identifies as male, was sent into servitude.

And while he’s telling his tale of Sheppard, Rosenberg is hyper aware of what he’s writing about (hence, the metafiction aspect of the book). The main text is a 1724 manuscript of the memoirs of Sheppard (fictional, obviously), but the footnotes are crucial to the story as well — and within the footnotes is the story of Dr. R. Voth, who found Sheppard’s manuscript and annotates it. The footnotes are both fascinating (to give you greater context for Sheppard’s story) and increasingly unhinged as Dr. Voth, a trans academic, tries to uncover the mysteries of Sheppard’s memoirs while also saving his own career.

Rosenberg writes the real-life sex worker Elizabeth Lyon (known as Edgworth Bess) as a woman of color: In the novel, Bess becomes Bess Khan, a woman of mixed-race descent (white mom; southeast Asian dad). Rosenberg explains his decision to reclaim Bess’s narrative to NPR:

In that material, she was not represented in a very kindly way in the period. She was represented as kind of the person that lured Jack into a life of crime. And I was sort of interested in re-envisioning that — really just writing it as a love story, more of a feminist take, where she isn’t sort of this vixen that creates this perilous path for Jack, but that there’s a kind of, like, consensual and jointly-shared hatred of capitalism that they embark on together.

As Dr. Voth writes in a footnote when Bess is introduced, “Given that London was not by any means a white city in the eighteenth century — and indeed that there were no legal prohibitions on interracial marriages at the time — we have to take the unquestion [sic] nature of Bess’s characterization as white as less a reflection of ‘actual’ history than as the occlusion of it.”

I love this idea — that Bess’s characterization as white is just assumed, and assumptions shouldn’t be a reflection of history but rather hiding true history. How many queer characters have been lost to history? Confessions of the Fox is at the forefront of books that take the stories we know and flips them on their head — that give voice to the voiceless, and stories to the story-less.

And this is what makes Rosenberg’s book so powerful: He reminds his readers that so much of history is forgotten. He is rewriting the history we’ve been taught and making it more queer and more diverse. While doing so, Rosenberg notes the difficulty white authors have writing characters of color. As he explains to Huffington Post, “My feeling was that the question of representation could not be left to the level of content alone, but that this question of a white author representing characters of color, which I find to be a very contradictory and complicated and, I’m sure ultimately on many levels, necessarily failed project of mine, that it was going to have to influence the form of the novel as well.”

Rosenberg, a trans Jewish professor of 18th century literature, gender and sexuality studies, and critical theory at University of Massachusetts-Amherst, is well suited to the subject matter. His fields of research intersect in this novel: 18th century literature, moral philosophy, political theory, queer theory, and Marxism. (And while Confessions of the Fox is his debut novel, Oxford University Press published his first book, Critical Enthusiasm: Capital Accumulation and the Transformation of Religious Passion, in 2011.)

Over the course of the story, Jack and Bess become partners — Vulture calls them “the Bonnie and Clyde of 18th century London” — embarking on adventures and falling in love. Rosenberg says in Slate, “the book is pretty dirty and contains explicit but non-spectacularizing material that I do hope might resonate with people in terms of some of the dynamics around queer and trans sex, intimacy, and how all that can get bound and tangled up with other kinds of political projects and impulses.” This is to say: He writes great sex scenes, without objectifying or fetishizing his characters. (Seriously. Great sex scenes. When I was reading Confessions of the Fox in a coffee shop, I almost felt like I shouldn’t be in public.)

When NPR asks Rosenberg if he believes “there’s a lot of history that can be rewritten or at least reimagined through the eyes of people who…had to live in the shadows, who were overlooked and discounted?” he answers, “I think we all know that what gets archived in the official archives, and what falls out, is not a neutral operation. So I guess my answer to you is yes, necessarily so. And yes.” Rosenberg writes into existence characters who have surely been lost to history.