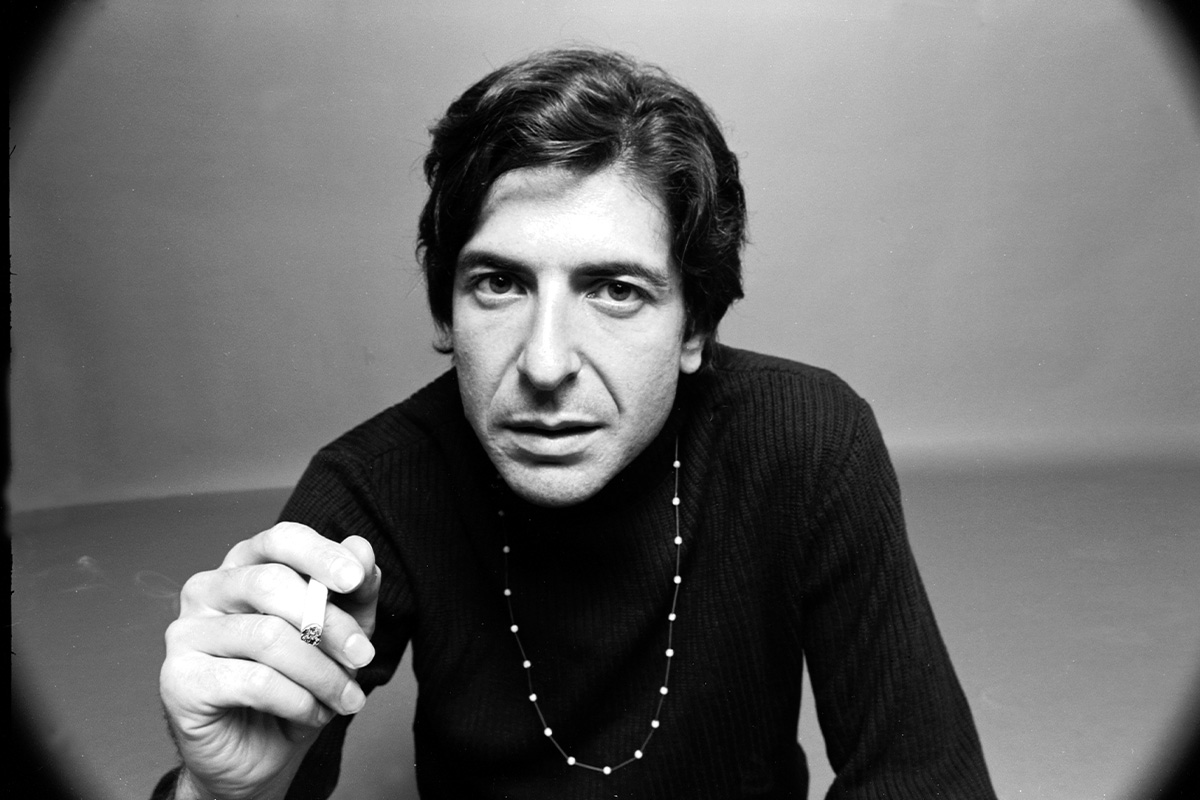

The co-founder of Ohr HaTorah Synagogue, Mordecai Finley, first met Leonard Cohen in August 2006, when the author of famous hymns like “Hallelujah” and “Suzanne” attended a wedding with his then-partner and fellow artist Anjani Thomas. Finley officiated, and after the ceremony, sat next to Cohen and Anjani.

Cohen asked about Finley’s denomination, and the rabbi jokingly replied, “Post-Orthodox neo-Hasidic.”

“He gave it a big laugh and just loved it,” Finley recalled when I spoke with him in September. Following the wedding, Cohen and Anjani joined Finley’s synagogue in Los Angeles, California and showed up for the rabbi’s Jewish spiritual psychology dharma talks on Monday nights.

Finley and Cohen became “spiritual study partners” of sorts, according to the rabbi. Cohen appreciated his breadth of knowledge in the field of philosophy, Jewish thought and Lurianic Kabbalah. Not only that, Cohen respected how “Reb,” as he came to call him, had internalized it all.

Cohen died in 2016. A new documentary released this year chronicles the musician’s life and work through one of his most widely recognized songs.

After viewing the film, Finley opted to expand his educational repertoire and offer a workshop called “The Theology of Leonard Cohen Through the Study of Selected Poems,” a five-week online course consisting of one-hour lessons that concluded this past September on Cohen’s birthday — and which I was lucky to attend.

“He was not a theological poet,” Finley said about Cohen in our initial gathering on Zoom. But spiritual concepts form the backdrop within his work. “When you look at the poetry, Lurianic Kabbalah leaks through,” Finley told his class of about 15 to 20 students in August.

An esoteric philosophy, a spiritual method and – many claim – a framework for mystical Jewish thought and experience, Kabbalah can also be considered a “theosophical” system, Finley’s students learned. If theology refers to ideas about the divine rooted in scripture, theosophy can refer to ideas about the divine derived from concealed and transcendent meaning in significant spiritual texts. You could conceive of Finley’s course as an introduction to the theosophy of Leonard Cohen, and you could call Kabbalah a kind of theosophy.

Cohen famously borrowed and repurposed a Kabbalistic metaphor in his song “Anthem,” as Finley discussed during the class. “Ring the bells that still can ring / Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack, a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in,” goes the refrain. In the Lurianic origin story, the Ein Sof, what’s infinite in extension and density – that “obsidian luminosity,” to borrow a phrase Finley used – long ago contracted out to create space filled by the absence of the divine. As light shined into the space of divinity’s absence, vessels holding the light cracked. What’s called the “Kabbalistic catastrophe” has to do with the breaking of the vessels or sefirot, the divine emanations. Cohen exercised poetic license, inverting the origin story so that rather than the light overwhelming and cracking the vessels, it’s the cracks within them, the brokenness, that lets the light in.

In “Anthem,” Cohen conjures up an image of the mythical breaking of the vessels incapable of containing the sacred splendor. He connects that motif to the mutilated nature of human beings – traits that ironically endear us to what’s holy, according to Cohen’s art and Finley’s course about its spiritual significance.

“We both agreed that depression and gloom – feeling disconnected, isolated – it’s a husk,” Finley told me. “But there’s a light in there. When he wrote, ‘There’s a crack in everything / That’s [how] the light gets in,’ that’s where that comes from. He deeply believed it.”

The concept also appears in Cohen’s song “Come Healing.” “O gather up the brokenness / And bring it to me now / The fragrance of those promises / You never dared to vow,” the song begins. Finley conceptually linked the lyrics to Psalm 51, wherein King David attests to the Lord’s preference for a broken spirit and affirms God won’t reject a contrite and crushed heart. The “fragrance” in the lyrics invokes the Kabbalistic metaphor of the vapor left behind after the contraction of the infinite – Reshimu, a barely detectable beatific blueprint.

If the purpose of life entails repairing the supernal, as certain Kabbalists contend, then part of that work entails coming to know your own brokenness. “If you don’t know you’re broken,” Finley said during class, “you can’t heal God.”

With the lucidity of an erudite professor and the equanimity of a Talmudic sage, Finley unearthed other spiritually-laden gems in the song during the online course. “O troubled dust concealing / An undivided love / The Heart beneath is teaching / To the broken Heart above,” Cohen continues on the track, incorporating a Kabbalistic imperative. That is, our broken spirit in this lower world must desire and aim to access and repair the damaged divinity residing in a world above, despite the difficulty inherent in doing so.

Put differently, poetry and art done well involves cracking and breaking those husks of darkness pervading a person’s inner life to release and raise the holy sparks hidden within. This is the same message Finley gave in his High Holiday sermon this year called “Break the Husk, Release the Spark.”

“I felt husks broken and sparks released when I read his poetry, and he felt it from my teaching,” Finley shared after his class ended, adding that he’s open to guiding future study of Cohen’s work. Anyone who shares a love for Leonard Cohen’s music and an interest in the spiritual philosophy underpinning it might appreciate Finley’s pedagogical approach aimed at letting the light in.

Rabbi Finley is offering a continuation of his class on the spiritual and religious background of the poetry of Leonard Cohen starting Tuesday, November 8.