On a warm yet windy afternoon last September, I found myself at the Art Institute of Chicago, wandering aimlessly with my friends. I was there because our professor had instructed us to visit and look at different artworks for inspiration for our first project in our Research Studio Art class, but nothing felt impactful for me. The museum was freezing and I was restless, so I snuck away from my friends and wandered around the modern art gallery. I passed Matisse, Picasso, Mondrian, Dalí and many more, but the works weren’t making me feel anything.

Then I saw “White Crucifixion,” a huge painting by Marc Chagall. The scenes it depicted felt too familiar. People running for their lives with their belongings shoved in a bag, houses on fire, an army with red flags and angels crying. In the center there’s Jesus on a cross with tzitzit. Above him are the words “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” in Aramaic. I’ve never been stunned by a painting before. I knew I had to learn more about Chagall.

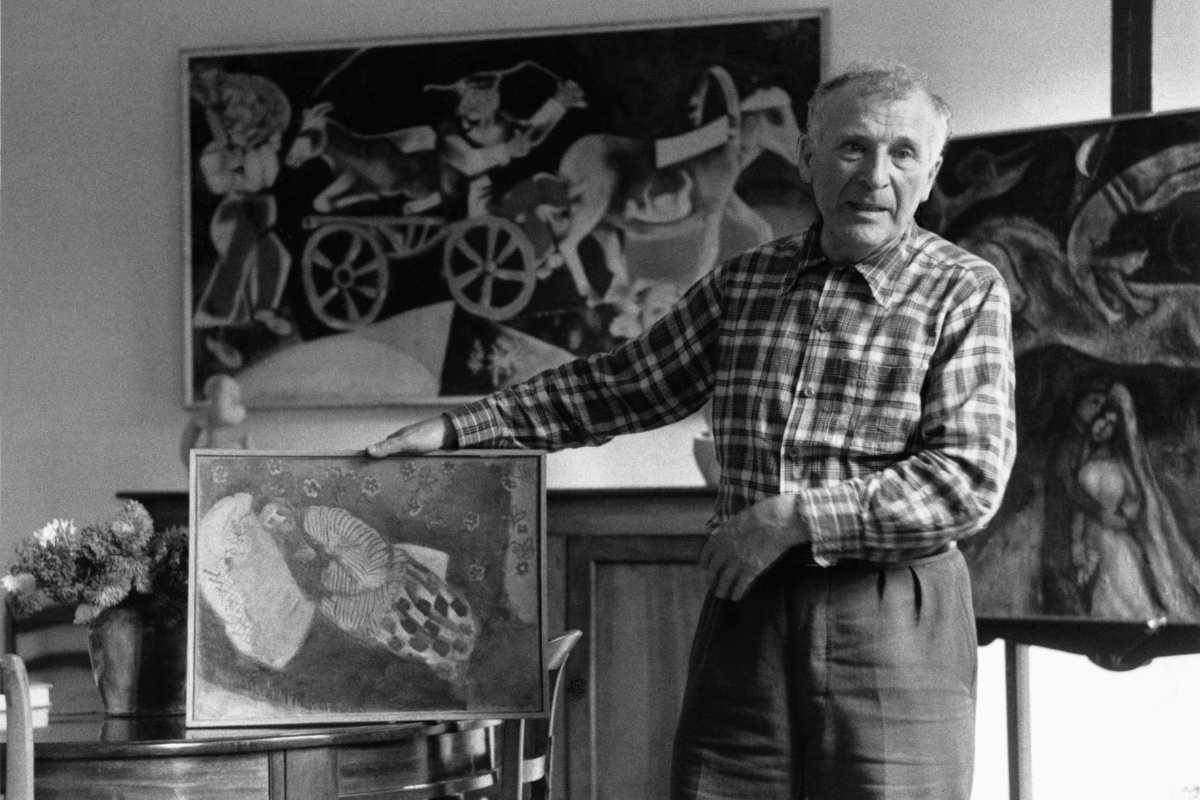

Each piece of his that I saw revolved around historical events, personal events and shared experiences. I felt deeply connected to the Jewish aspects of Chagall’s work, but when I tried to research this part of his art, I was unsatisfied with what I found. It felt as though his traditions were erased, which was particularly upsetting because I learned he primarily painted Jewish traditions and memories of home because he felt that the traditions that he grew up with were disappearing. His art was his way of preserving them for the next generations.

I knew I had to make my presentation about Marc Chagall. While researching him I learned that he was raised a Hasidic Jew and had dealt with so much antisemitism in his lifetime. He had survived a pogrom as a child by claiming he wasn’t Jewish, was forced to pay university tuition while non-Jews in Russia were not, and he survived Nazi occupied France. I worked all these facts into my presentation.

I was nervous the day of the presentation. None of my classmates were Jewish, and they did not know I was Jewish. My past experiences with antisemitism in school environments made me fearful about what might happen if my classmates learned my identity as a Jew. I stopped before I opened the door to my classroom. I was so nervous that I quickly whispered the Shema to calm myself down.

My classmates did have questions about Judaism, sort of. As I stood at the front of the room, a student in the back row raised his hand and innocently asked, “What’s a pogrom?” I knew this student; he was kind and genuinely asking. But I got nervous. To be honest I thought everyone knew what a pogrom was.

“Pogroms are organized massacres of Jews,” I said quickly, swaying my body to try and regulate my stress, speeding my way through the definition. The boy who had asked the question looked uncomfortable, and other students nervously looked around at each other avoiding eye contact with me. I felt my voice rise to a higher pitch as I continued my explanation: “A lot of my family members were murdered in them. Some of us survived though! Which is how I ended up here!” I felt my knees lock and the sweat drip down my neck. It was a terrible example and an incredibly rushed definition, but I had not been prepared for this kind of questioning at all. When I finally looked up from the floor and made eye contact with my teacher, who looked extremely concerned, I realized I’d done exactly what I’d hoped to avoid. My mouth became dry and I felt the blood drain from my face. I just told my whole class that I’m Jewish.

I’d heard horror stories about antisemitic behavior at other colleges, and I was afraid of what might happen if my classmates knew that I’m a Jew. I felt my mind spiraling as I took my seat at the end of my presentation — had I made everyone uncomfortable? Would I lose friends? In the coming days, I was relieved to realize my fears didn’t come true. Nobody hated me. I decided that like Chagall, I would always incorporate Jewish elements into my future art works. My Jewish identity would be a purposeful central theme in my work. I wanted to embrace my Judaism; I didn’t want to hide.

For our next class project we each had to make a piece that was heavily inspired by our chosen artist’s style, yet also had our own elements. I chose to make a piece that was inspired by “America Windows.” In each panel I saw my own family history being played out. I saw my family celebrating the Jewish holidays, singing, dancing and lighting a menorah. I saw long journeys, one taken by my ancestors that fled the Spanish Inquisition, one taken by my great-grandfather fleeing Germany, one taken by my family fleeing Poland, Turkey, Ukraine, you name it. I saw the journey that my mother took from Israel to America. I saw my childhood, family dinners and my dreams.

Chagall made the windows to celebrate America’s second century of existence and featured iconic American landmarks, such as the Statue of Liberty and the Chicago skyline. I made my work to celebrate my family’s existence with our own landmarks.

In the middle section of “America Windows” there is a cityscape with plants in the sky, the Statue of Liberty, desks with feather quills and books. In the foreground there is a giant pink bird with purple shadows and tiniest hint of green. It has black defining lines on each piece of glass. To me the bird symbolizes myself, as I have left home for the first time and am living on my own. But unlike Chagall’s bird, mine is surrounded by things that remind me of my family — a watering can for my mother that has Ima written on it in Hebrew, hidden music notes for my sister who is a drummer and a half a guitar for my father — because they are the people who define my world.

I drew my design on parchment paper. I used multiple coats of Sharpies to act as the lines between each piece of glass. To replicate the colors and shifting light, I used two arduinos (small computers), ten LEDs (eight of which were RGB LEDs meaning that I could customize the colors that they emitted), 63 wires and two nine-volt batteries. I had coded each color value and each LED group. The lights shone through the parchment, echoing the way the light shines through Chagall’s windows. The lights shifted colors and gently pulsed and shifted location, mimicking the way the light changes through stained glass as the sun moves in the sky. The final product was beautiful. The final step was to present it to my peers in class.

The night before my critique, I was astronomically excited. Everything was planned: my presentation speech, my outfit, even my makeup.

The piece was very well received. I got some negative comments about technology being used as a medium, but I was still really proud of myself. It was my first art project of my university career and I had done what I had set out to do. I, like Chagall, had made Jewish work about my own memories of home.

As I walked back to my dorm after class, feeling light and carefree on Oct. 6, 2023, I thought to myself: This is the happiest day of my life.