When I was in college, I was a math whiz. Not in the academic sense, but in the culinary one. I could tell you the exact caloric count of everything from a hard-boiled egg to half a cheese stick from 7-11 to a sandwich from the Subway across from my dorm (no cheese, whole wheat flatbread, lettuce, pickles, and oil and vinegar only). I would go to my morning classes without having eaten since the afternoon before — I have a vivid memory of my stomach rumbling so loudly in one class that the person next to me was actually alarmed by the sound. I would never go out to eat with people, so I had no friends; eating was a strictly private, scientific task, best performed alone in my tiny dorm room.

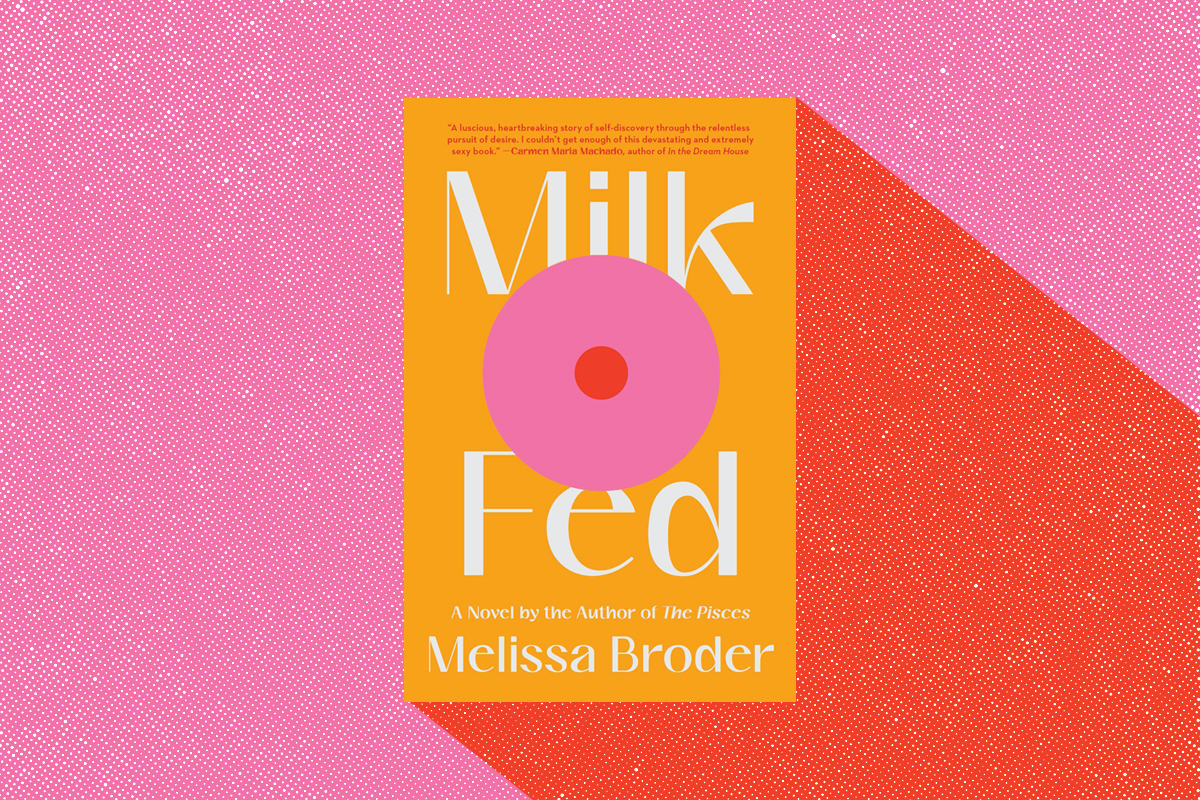

It was the darkest, most isolating time in my life, and I have never felt so seen as I did when reading Melissa Broder’s new novel, Milk Fed. As a queer Jew-in-progress who still sometimes struggles with the little voice in my head around food, Milk Fed is the story of Jewish self-love that I need in these tumultuous times.

The main character, a secular Jewish woman named Rachel, also obsessively counts calories, never dining out except when required for her job, and eats protein bars in the bathroom to avoid anyone seeing her eat. That is, until she meets Miriam, an unapologetically fat, frum woman who works at her family’s frozen yogurt shop. Miriam ignores Rachel’s insistence that she wants plain yogurt, no toppings, and never above the rim of the container (to better to know exactly how many calories she is consuming). She provides Rachel with beautiful, rich yogurt sundaes and a sense of appreciating both Judaism and the little things in life. Eventually, Rachel falls head over heels.

When her therapist asks Rachel to sculpt the “out of control” body she is so afraid of becoming, she creates a clay woman with “massive thighs, weight calves, a voluminous ass.” This sculpture, which Rachel later researches and decides might be a golem, becomes the catalyst for her to explore Judaism and find some self-acceptance along the way. She googles what a golem is and learns about the story of Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, who begins appearing in her dreams, telling her that noshing is a mitzvah, as is having sex with Miriam on Shabbat. For me personally, and as Rachel begins to learn, Judaism is not just a set of strict rules that tell you what you can’t do. Instead, it’s a way of living life that helps cultivate joy and appreciate things in life that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Miriam invites Rachel to dinner at a kosher Chinese restaurant, where she tells Rachel that not only is the whole restaurant, immense portions of food included, “God,” but the giant, fruity cocktail they are drinking is the most holy of all. For someone with disordered eating, food is the enemy. And community, the cornerstone of Jewish culture, can become the enemy by proxy. How can you enjoy a Shabbat dinner when you don’t know the amount of calories on your plate?

When I make challah on Fridays now, I don’t think about the calories in each loaf. Instead, I think about the mindfulness inherent in the mitzvah, the other people around the world also making challah before Shabbat, and the families who will share it. There is love in challah, along with history and Jewish joy. This small act is a big statement, especially for someone with a difficult relationship to food. The fact that Judaism urges us to bless and appreciate our food is a powerful statement about loving not just the world, but what we give ourselves.

While she makes some serious missteps with Miriam and doesn’t quite understand or respect all the nuances of observant Jewish life or Miriam’s boundaries, Rachel comes to appreciate and develop her own Judaism, taking the pieces that are most meaningful to her and allowing them to shape her view on the world. In one of her dreams, Rabbi Loew ben Bezalel tells her, “There are emanations of god we can’t even see. What’s important is you feel it.”

There is also empowerment in tradition. Just as I feel the legacy of Jewish culture when I make challah on Fridays, Rachel connects queerness with the legacy of Jewish women. She reflects that over the centuries, in the mikveh, “women [were] naked in the same hothouse. Some of them must have secretly gotten it on.” Imagining the legacy of Jewish queer women that have been silenced in our tradition is revolutionary and incredibly moving. This is the Judaism I want to be part of, and the one that leads Rachel to a path of true self-love.

Part of my own Jewish journey as I continue with my conversion process has been figuring out where I feel the divine the most, and engaging with those moments as much as I can. Similar to Rachel, I often feel it when in groups of people where I am comfortable to be myself fully. There is empowerment in finding community and living your life in accordance with that. Of course, there will always be compromises and challenges, but the struggle itself is the joy when it comes to Judaism, at least for me.

Just like what the rabbi tells Rachel in the novel, we are all our own golems (which in Hebrew originally meant “unfinished substances”), doing the best with ourselves and the people we meet, sometimes less than they (or we) deserve. Milk Fed showed me that Judaism has a place for all of us, golems included.