On the eve of his inauguration, incoming President Joe Biden held a memorial for the more than 400,000 Americans who have died of COVID-19. After an acknowledgment of the nation’s grief by incoming VP Kamala Harris, Lori Marie Key, a Detroit nurse who sings in her COVID ward to bring joy, performed “Amazing Grace” a cappella. Then, Joe Biden spoke. “To heal, we must remember,” he said. “Between sundown and dusk, let us shine the lights in the darkness, along the sacred pool of reflection, and remember all whom we lost.” At that moment, 400 lights, each one representing a thousand people lost to the coronavirus, were illuminated along the edge of the basin. As the ceremony culminated with sweeping shots of that famous place, with the Lincoln Memorial at one end and the Washington Monument at the other, Yolanda Adams sang Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.”

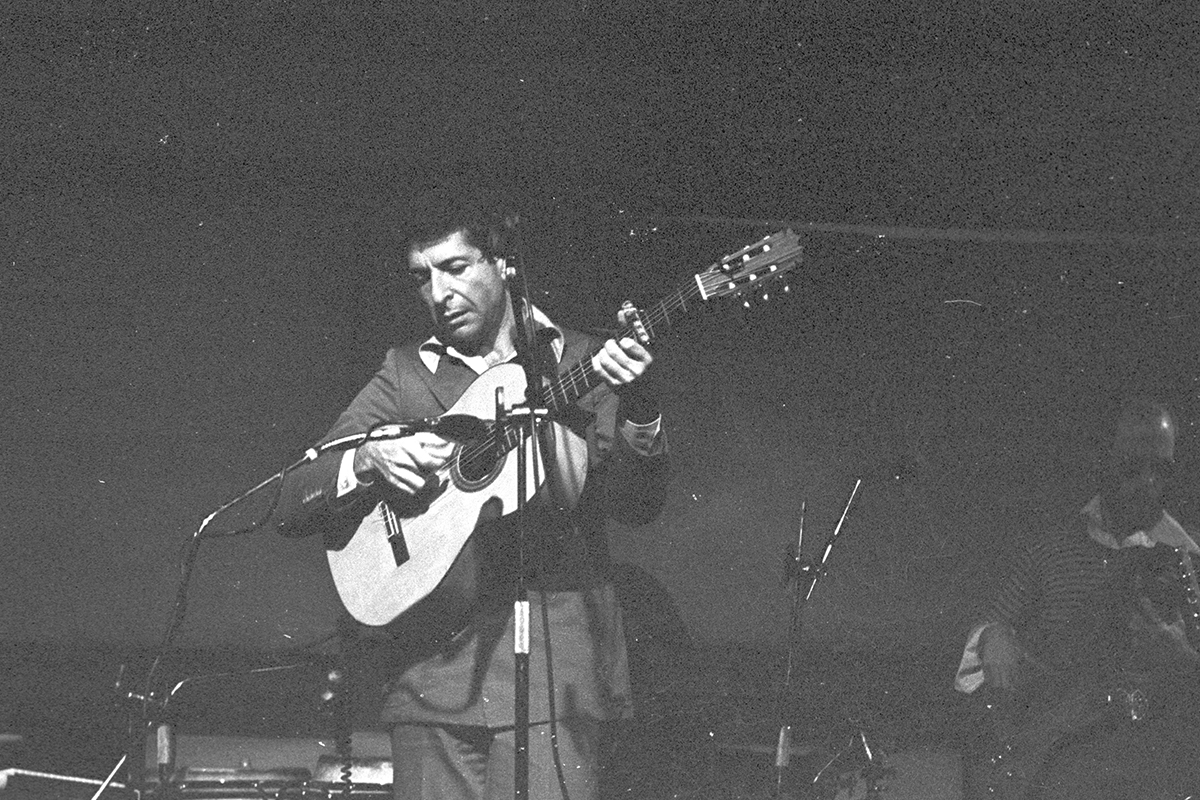

“Hallelujah” may be one of the few subjects on which Trump and Biden agree: Trump also played the song at the Republican National Convention in 2020, which led to a rebuke from Cohen’s estate. It is a law of the universe that “Hallelujah” makes momentous, emotional events feel… more momentous and emotional. This means it’s been in almost every TV show that’s run longer than two seasons at least once. (It may also be the only thing Ugly Betty, NCIS, and Shrek have in common.) Cohen himself commented on its overuse. “I think it’s a good song, but I think too many people sing it,” he told the Guardian in 2009.

It still does it for me. “Hallelujah” never fails to move me, and I’m not alone. It’s been covered by artists ranging from Bob Dylan to k.d. lang to Pentatonix, and it remains Leonard Cohen’s best-known song, even if many people don’t know that he wrote it, thinking instead that it’s by Jeff Buckley, who recorded its most famous version. That is arguably Jewish erasure, because “Hallelujah” is one of the more Jewish songs ever written. And its message might not be quite as inspirational — or appropriate — as these tribute planners and TV showrunners think it is.

Idk who needs to hear this but Hallelujah is a song about Jews clapping cheeks and questioning the existence of hashem

— Rebecca Pierce (@aptly_engineerd) January 20, 2021

Not only is Leonard Cohen Jewish (I mean, Cohen, come on), born to a Jewish family in Montreal, but the song’s lyrics are full of sexy references to the old Testament — in particular, to ancient Israel’s rock star, King David.

Most people know King David for his Biblical defeat of Goliath the Philistine, an inspiration to underdogs everywhere. But when David was still only a shepherd, he first found fame as a musician. “Hallelujah” opens with the phrase: “I heard there was a secret chord / that David played, and it pleased the Lord.“

This likely refers to the moment when David’s musical gifts saved King Saul from evil. Per Rolling Stone: “‘And it came to pass, when the evil spirit from God was upon Saul, that David took a harp, and played with his hand: so Saul was refreshed, and was well, and the evil spirit departed from him (1 Samuel 16:23).’ It was his musicianship that first earned David a spot in the royal court, the first step toward his rise to power and uniting the Jewish people.”

The next line — “But you don’t really care for music, do you?” — also feels pretty Jewish, but for a very different reason. As Alan Light wrote in his book about the song, “This first verse almost instantly undermines its own solemnity; after offering such an inspiring image in the opening lines, Cohen remembers whom he’s speaking to, and reminds his listener that ‘you don’t really care for music, do you?’ One of the funny things about ‘Hallelujah,’ said Bill Flanagan, ‘is that it’s got this profound opening couplet about King David, and then immediately it has this Woody Allen–type line of, ‘You don’t really care for music, do you?’” Nothing more classically Jewish than undercutting yourself with some self-deprecating humor.

The song goes on to describe its own musical progression — “minor fall, major lift” — before returning to David with the closer, “the baffled king composing Hallelujah.”

King David wasn’t just a divinely-gifted musician — he was also, in the words of My Jewish Learning, “a stud. ‘David’ means ‘beloved’ — of both God and humankind, especially women. It was the latter who used to chant (much to the consternation of David’s predecessor King Saul): ‘Saul has slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands!'” “Hallelujah” nods to one of his more famous episodes of womanizing in its second verse:

“Your faith was strong, but you needed proof / You saw her bathing on the roof / Her beauty in the moonlight overthrew you.” This alludes to David’s adulterous affair with Bathsheba, a beautiful woman married to a soldier named Uriah. “And it came to pass in an eveningtide, that David arose from off his bed, and walked upon the roof of the king’s house: and from the roof he saw a woman washing herself; and the woman was very beautiful to look upon.” (2 Samuel 11:2). After that fateful rooftop meeting, David seduced and impregnated Bathsheba. Then, to cover up his transgression, the king ordered Uriah home from war to sleep with his wife, so he would think the child was his. (A very intense move.) But Uriah chose to stay. So David sent him to the front lines to be killed, and married Bathsheba himself.

Inspiring!

Light’s book paraphrases a sermon on David and “Hallelujah”: “The story of David and Bathsheba is about the abuse of power in the name of lust, which leads to murder, intrigue, and brokenness. Until this point, David had been a brave and gifted leader, but that he now began to believe his own propaganda – he did what critics predicted, he began to take what he wanted… David is God’s chosen one, the righteous king who would rule Israel as God’s servant. The great King David becomes no more than a baffled king when he starts to live for himself. But even after the drama, the grasping, conniving, sinful King David is still Israel’s greatest poet, warrior and hope. There is so much brokenness in David’s life, only God can redeem and reconcile this complicated personality. That is why the baffled and wounded David lifts up to God a painful hallelujah.” It seems safe to infer that Leonard Cohen, who had his own complex history with women and music, saw himself in this “baffled king, composing.”

This isn’t the only reference to a sexual, worldly episode destroying a man with a higher purpose in the song. The next line jumps to another famous Biblical story, that of Samson and Delilah: “She tied you to a kitchen chair / she broke your throne, she cut your hair.” Samson, arguably the first Jewish superhero, drew his power from his hair. Delilah, the woman he loved and maybe also a weapon of the Philistines, learns the secret source of his strength and shaves his head while he sleeps, leading to Samson’s capture. Cohen ends this verse with “and from your lips, she drew the Hallelujah” — with “Hallelujah” as a cry of bodily, rather than religious, ecstasy.

The lesson in these stories is clear: that “even for larger-than-life figures and leaders of nations, the greatest physical pleasure can lead to disaster.”

So it turns out that “Hallellujah” isn’t just overused — it’s also misused. It’s definitely not a hymn, as many people believe, and it’s also maybe not the best choice for, say, memorials to the dead.

It may still be pertinent to the moment, even if not in the intended way. Leonard Cohen wrote “Hallelujah” at a low point in his career. He had fallen from grace, too: Both of his previous albums had been “commercial and critical disappointments,” and though the song was released in 1984, it wasn’t recognized as anything special until Bob Dylan began to cover it four years later. But it went on earn a place on Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

So while it may not be the feel-good anthem so many people seem to think it is, maybe it makes sense that “Hallelujah” has continually popped up in our national discourse. Examining these stories of powerful men toppled by their carnal urges, it’s hard not to think of the now-former President who left D.C. on Wednesday — a man who utterly failed to manage the crisis of the pandemic, and therefore allowed America to reach the horrific milestone of 400,000 dead.

Let’s hope that the story of “Hallelujah’s” writing — from ruin to glory, not the other way around — proves more relevant than the stories it actually tells. As it did for Leonard Cohen, may the song herald the beginning of the end of a dark time. Hallelujah.