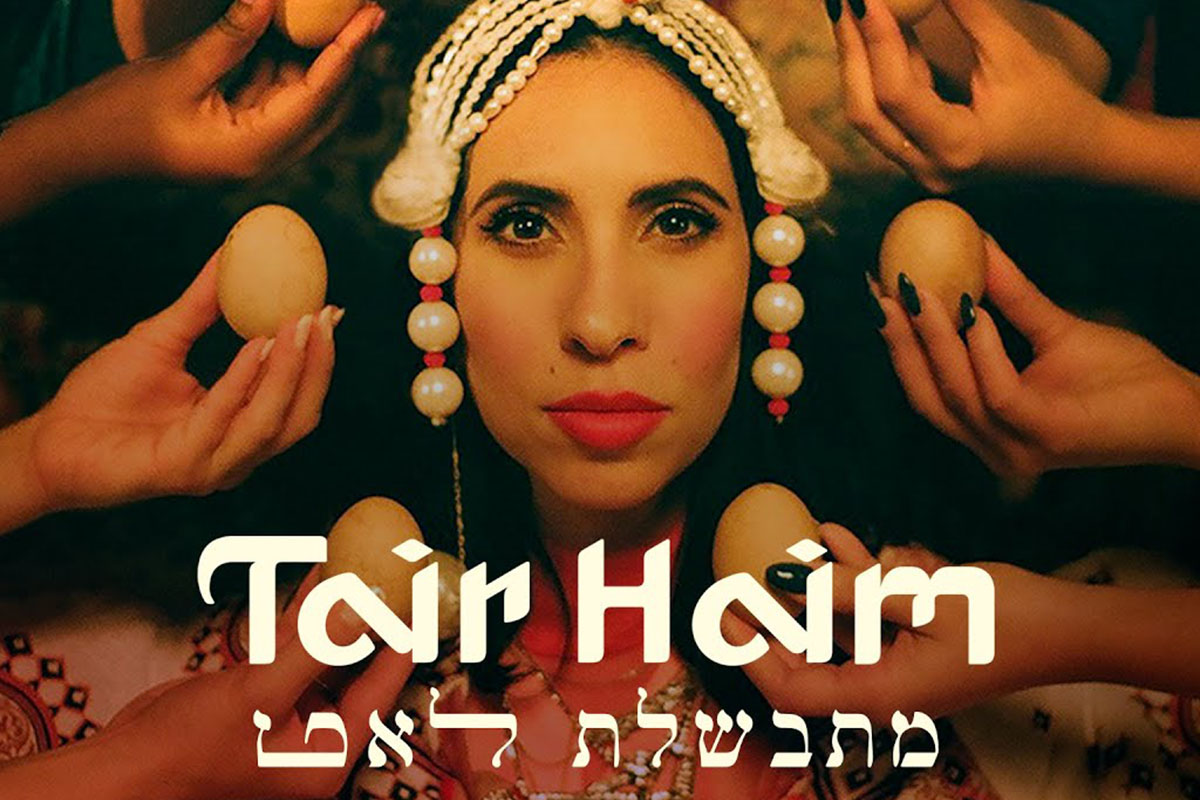

When I first saw the promotion for Tair Haim’s new single, urgent questions raced through my mind. Is she going solo forever? Will all her new music be in Hebrew? What will happen to the beloved Yemenite tunes she’s been making with her sisters in their band, A-WA? Despite all my snooping on Instagram, I have yet to get answers to these questions. But it’s almost irrelevant to dwell on it at this point, because her new music video is so, so good.

The first 20 seconds of the video tell you all you need to know about her bold solo statement. The Yemenite Arabic phrase “Kheli ya hali” repeats over a powerful drum beat, while the camera pans over luxurious red and gold carpets until we see Tair, decked out in a resplendent gown, jewelry, and headdress. It couldn’t be more clear — Tair’s Yemenite pride isn’t going anywhere. It’s here to stay.

The first two lines of the song hook you in to its message. “I simmer slowly,” she croons in Hebrew, “like Chamin on Shabbat.” At this point, eight hard-boiled eggs are thrust into the camera, framing her face. I recognized the meaning of this juxtaposition instantly. Chamin is the catch-all phrase for a slow-cooked stew that is prepared on Shabbat, simmering for hours from Friday evening until Saturday lunch. Jewish communities from the diaspora have different versions — Ashkenazim are familiar with cholent, Iraqis take pride in their chicken and rice dish called “t’bit,” and Moroccans stew a meaty dish alternately called “sechena” or “dafina.”

In my father’s Moroccan home, the flavor of our sechena was distinct. An aunt would prepare it and then it would sit for hours on the plata, or stove top heater, until the rich chunky stew was served. There were always hard-boiled eggs in the stew that had turned brown — there’s nothing quite like their distinct, smoky flavor. Yemenite chamin also often contains eggs as well. But the meaning of the eggs goes beyond the literal. In many cultures, eggs are a symbol of fertility, and they are used in Yemenite wedding rituals to bode for a healthy reproductive life. In more than one way, the eggs represent the importance of feminine labor.

The next few moments of the video show off the dancers’ insane skills (dancing with eggs, no less). But Tair is stationary, and remains either sitting or standing in place for almost the whole video. She doesn’t move towards the camera; the camera moves towards her. Her stance radiates power. This imagery reminds me of a phrase coined by the writer Jenny Odell: “resistance-in-place.” Odell writes, “To resist in place is to make oneself into a shape that cannot so easily be appropriated by a capitalist value system. To do this means refusing the frame of reference [in] which value is determined by productivity.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CAGHH7SgM4C/

Tair’s refusal to alter herself into an easily consumable form are echoed in her lyrics. “So don’t chew me like fast food,” she sings, and later, “I’m not easy to digest.” She stubbornly resists any model that is conventional in the music industry. She rejects what her critics want in the lyrics, “You wanted me in Hebrew already / But my heart sings in Yemenite.” Rather than an outright rejection, this refusal is playfully subversive. She sings the song in Hebrew after all, but pronounces the word chamin with the “chet” of a Yemenite accent. This echoes Odell’s kind of refusal — not saying “no” outright, but instead refusing the frame of reference altogether.

In the next minute of the video, the playful destruction of ‘50s era symbols is a familiar rejection of misogyny. We see a rotary phone drowning in soup, kitten heels placed on a table, the burning of a retro alarm clock. But the imagery that the video celebrates is timeless. The abundance of gold jewelry is a nod to Mizrahi women who have been wearing them for centuries. (My own Moroccan grandmother never took her gold bangles off, which made a gentle clinking sound as she handled various pots in the kitchen.) Although it may seem like a small detail, the use of red lipstick and gold jewelry is a celebration of Mizrahi ideals of beauty in a country whose advertising prioritizes models who are white, blonde, and take up as little space as possible. Tair’s embrace of an old-school Mizrahi aesthetic suggests that her music is rooted in the past as much as it innovates in the present. Her feminism nods to something more ancient, celebrating the jewelry and customs of her foremothers.

As good as the video has been so far, the big reveal is at the end. With the help of her dancers, Tair finally stands up from her throne, walks to the camera, and turns to the side. Her silhouette shows off her pregnant belly. She is radiant as she rubs her stomach and smiles. It’s then the viewer realizes that the whole time she’s been sitting, her body was going through internal cycles of growth. She’s simmering, growing, becoming who she is, and preparing to pass on her legacy to the next generation.

Header image via @tairhaim on Instagram.