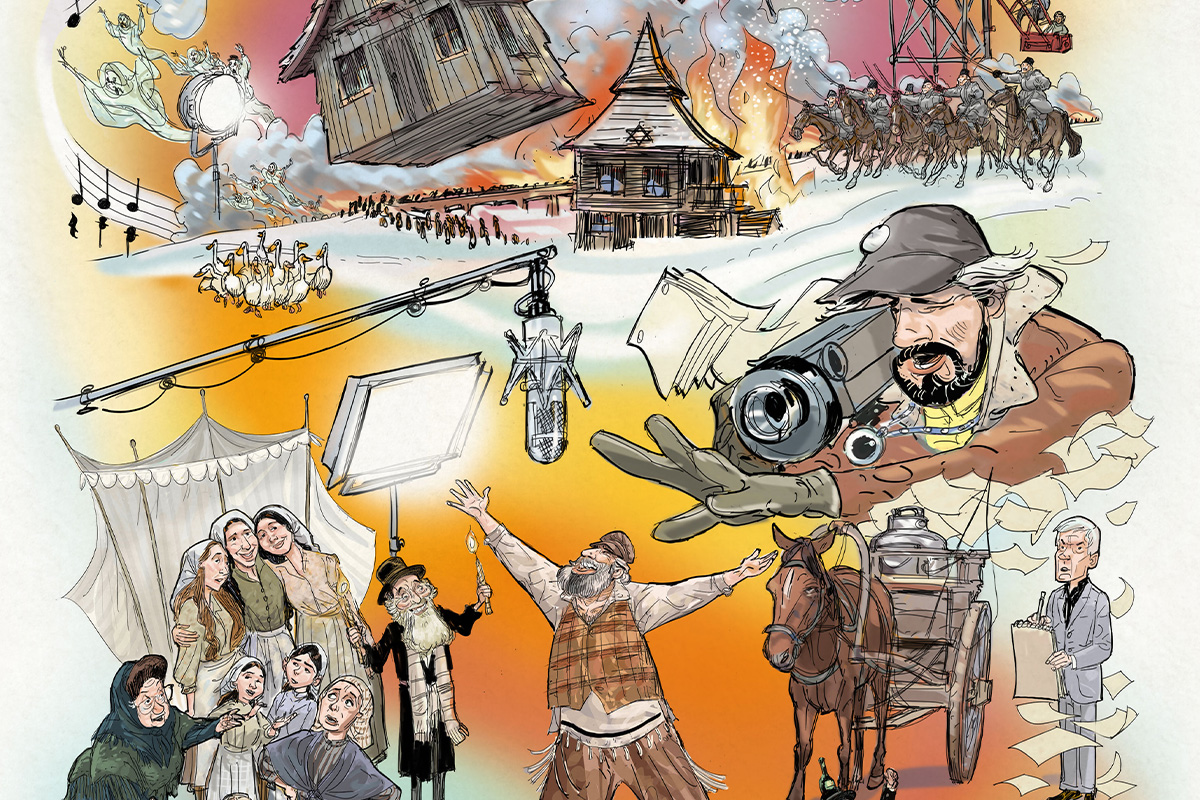

For more than 50 years, “Fiddler on the Roof” has been among the most beloved films in the Jewish canon. To celebrate the musical, filmmaker Daniel Raim spent over a decade creating the new documentary “Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen.” With original interviews from many of the cast and crew members and narration by Jeff Goldblum, the documentary reveals the musical’s heart and explores how a humble Jewish tale became an international phenomenon.

While Raim is just one filmmaker with one perception of “Fiddler on the Roof,” his experience with the movie and sense of its place in the world today ring true. You can’t think about the shtetl today without thinking about “Fiddler” — but you also can’t think about “Fiddler” today without thinking about the current state of Eastern Europe and Russia.

In speaking with Raim and watching “Fiddler’s Journey to the Big Screen,” I gained some insight into what makes this movie, produced with hardly a Jew involved, such a quintessential telling of the Ashkenazi Jewish experience — and why it’s still such a universal story today.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and brevity.

What is special about “Fiddler on the Roof” for you personally?

I first saw “Fiddler on the Roof,” the movie version, with my grandparents at their home. It made quite a strong impact on me. My grandparents are survivors of the Holocaust and, sadly, their siblings and parents did not survive. The music and the story itself were so powerful and moving and engaging. It connected with my own curiosity about Jewish history and inspired me to learn more about where my ancestors came from, how they lived, how the State of Israel was created, and what the political forces were that led Jewish people out of Eastern Europe in 1905. Seeing that movie was a window into a world that doesn’t exist anymore.

What about the movie’s production and history made you want to make a whole film about it yourself?

That’s a great question and a lot to unpack. Over the last 20 years, my focus has been making documentaries about unsung heroes, often working behind the scenes and behind the cameras: production designers, cinematographers, directors. Their art, and humanizing the artform. One of my very first mentors at the American Film Institute was Hitchcock production designer Robert Boyle, who was also the production designer for “Fiddler on the Roof.” So, when I was graduating from AFI, I asked Boyle for permission to make a documentary about his life and his work. And that of course led to talking about “Fiddler.”

In 1999 I interviewed “Fiddler” director Norman Jewison and was totally taken by his personality and his storytelling, not just on screen but on camera. When I was interviewing him at the time, he really helped elevate my Robert Boyle documentary “The Man on Lincoln’s Nose.” I first had the idea to make this “Fiddler” documentary in 2009 after seeing Chaim Topal’s farewell tour in LA. I was moved seeing “Fiddler” on stage for the first time — and with Topol! And the audience at the Pantages Theater was of so many different backgrounds, I just thought, wow, this story and this movie and this play connect with audiences on such a deep level, I’d like to know more.

And that led to me conducting a series of interviews over the years from 2009-2021 with the cast and crew of the film. But ultimately, I felt that what I was excited about was to get into director Norman Jewison’s shoes, and get into his heart and mind and soul, and find out what his journey was. I thought that could make a strong story. Ultimately, it’s my love for “Fiddler,” for Robert Boyle, for Norman Jewison, and my own curiosity about how they could put together such a timeless masterpiece.

It’s clear in the way the documentary is put together that Jewison is one of the most essential pieces of what makes this movie version of “Fiddler” what it is. What about him as a person do you think most impacted the way “Fiddler” ultimately came together as the beloved film that it is?

This is a filmmaker who brings incredible empathy and concern for people into his storytelling. I think that it starts with the irony of his last name. From the age of 6 he thought he was Jewish. He’s not. But he went with his friend to Hebrew lessons and to synagogue and was really moved by Jewish culture. He made a spiritual connection with Judaism at that young impressionable age that never left him.

In the late ‘60s, he was experiencing a spiritual crisis spurred on politics and the assassination of one of his close friends, Bobby Kennedy. It had him really feeling like he might have to just give up making films because he didn’t feel that joy anymore. And it just happens that at that time, he was asked to direct “Fiddler on the Roof.” He really leaned back into that spiritual connection he had with Judaism: He went to Jerusalem and met with survivors of the Holocaust and pogroms. He really learned directly from survivors, making that connection with them where he felt a social obligation to tell their story. He was already a social-minded director, making socially driven movies about his own social concerns like “In the Heat of the Night.”

Beyond that, he was able to marry his incredible talent for directing actors, moving the camera and producing musical comedy. He also did a brilliant job of casting and picking the incredible team, including John Williams and Robert Boyle and Oswald Morris, to make the film. Jewison was already at the top of his game in terms of command of visual language and structure, and was really able to work with some of the top talent in Hollywood to design the visual language of “Fiddler on the Roof.”

Who else would you highlight as especially essential to the heart of the movie?

The real discovery for me in the edit was how powerfully I connected with the three actresses who played Tevye’s oldest daughters, Rosalind Harris (Tzeitel), Michele Marsh (Hodel), and Neva Small (Chava). We see them 50 years later and we understand their humanity and their personalities powerfully. Jewison was creating a family on screen — beyond Tevye and the A-list talent behind the scenes, these three daughters, they’re the heart and soul of the movie. A large part of why I think this movie was so successful was their charisma and their personalities and just who they were as people, not just actors. These were three actresses who had never acted on camera before, and they really brought themselves into the characters. I was just so glad to capture them 50 years later.

I also learned that “Fiddler” has a special place in the hearts of everyone who worked on the film. Including John Williams, who, as we know, is the maestro of cinema — and yet when he talks about, “Fiddler on the Roof” he remembers everything, even the smallest little detail. And he loved working with Norman Jewison, even though they never collaborated again on another project. Also, I think it’s interesting to note that all the department heads, really all the key figures behind the movie — the director, the composer, arranger, conductor, production designer, editor, cinematographer — none of them were Jewish. And yet, they made one of the single greatest Jewish movies ever made. And to me, that points to the power of their artistry and humanity, as well as to how cinema is a universal language.

I once sang “If I Were a Rich Man” in my kitchen while making breakfast and my neighbor chimed in through the wall. So, clearly, it’s a quite universal film. And that universality is a focus of the doc as well. Yes, “Fiddler” is about a Jewish experience very specifically, but in your own words, what makes this tale of traditional Jewish life, religion and struggle so relatable to lived experiences the world over?

It has to start with how specific it is about the rituals and traditions of Jewish life. It’s certainly rooted in a very specific exploration and celebration of Jewish culture and Jewish life. It’s also all rooted in this one family and the mind and heart and soul of this milkman who takes his issues to God. He’s very charming and lovable, and we understand his frustrations. And the frustrations he has, those are universal: He wants his daughters to be happy, but he’s torn, because tradition.

I think that’s where they tap into the universal experience of the tensions in all families — the relationship between parents and children who want to move away from the traditions of their mothers and fathers. We all understand that. Wherever you are on the planet, whatever culture you come from, whatever language you speak, you can identify. So that’s why I think the movie, which could reach millions and millions of people across the globe, unlike the play, really had a huge cultural impact and is beloved to this day.

And that comes back to what I was experiencing with the Topol farewell tour in LA in 2009. The diversity of the audience was incredible. I think the creators of “Fiddler on the Roof” — lyricists Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock, screenplay writer Joseph Stein and original stage director Jerome Robbins — did an incredible job adapting this Yiddish author, Shalom Aleichem’s, stories, and creating this world called Anatevka that never existed. It was a Jewish shtetl that was unlike anything that really ever existed. Shtetls were usually market towns with multiple groups living there, not just Jews. Yet, we feel the issues and concerns today maybe even more poignantly because we see the images of the exodus at the end of the film reflected on our televisions today, unfortunately.

Your documentary spends a lot of time focusing on the balance the movie strikes between tragedy and joy, beauty, and destruction. After spending so much time with the movie and the people that made it, is “Fiddler on the Roof” a hopeful movie or is it a tragedy? Does it matter?

I think the hope that I find is the act of preserving history. Jewison, as a filmmaker and a storyteller, addresses socio-political issues through his films. He intended to do something with the movie that the play couldn’t, which is to show the pogrom, the exodus. He also had visited Israel and become quite moved by his encounters with survivors of pogroms and the Holocaust, and was moved by the Zionist movement of that time. I think the act of hope in “Fiddler on the Roof” is preserving that history and that memory so we can learn from it.

What makes the movie so special for me is that when we see the scenes of the people leaving Anatevka with their worldly belongings, we see them sloshing through the mud. They’re singing that incredible song, “Anatevka,” that was so beautifully composed by Jerry Bock and written by Sheldon Harnick. The verisimilitude of it being a movie photographed in Eastern Europe, with the sets that Robert Boyle built, leaves you feeling like we are all Anatevkans. We are leaving Anatevka in a way that is so profound and so powerful, and I think that’s what makes the movie of “Fiddler on the Roof” a timeless masterpiece.

“Fiddler’s Journey to the the Big Screen” begins a limited theatrical run on Friday, April 29th.