Idina Menzel doesn’t like using the word “spiritual.” It’s towards the beginning of our 30-minute Zoom conversation about her new Broadway musical “Redwood,” and the 53-year-old Tony Award winner is explaining how it feels to sing, dance and flip through the air around the massive fake redwood tree at the heart of the show’s set. But she pauses to tell me this. I couldn’t agree more. In my experience, words like “spirituality” and “faith” have an evangelical Christian or woo-woo celebrity Kabbalist connotation. At best, they feel insincere. At worst, lightly oppressive.

“But it is spiritual,” Menzel says. “The energy that goes back and forth, the reciprocity and connectivity of the performer and the audience, what we give each other, it’s a very profound experience for me. I feel closest to my authentic self. It’s when I feel the closest to some kind of higher power.”

So, too, is “Redwood” a sacred, divine, yes, even spiritual experience. But whatever the right word to encapsulate the intimate soul-searching currently performed onstage at the Nederlander Theatre eight times a week might be, it’s undeniable that this show is deeply rooted — pun not intended — in Jewishness.

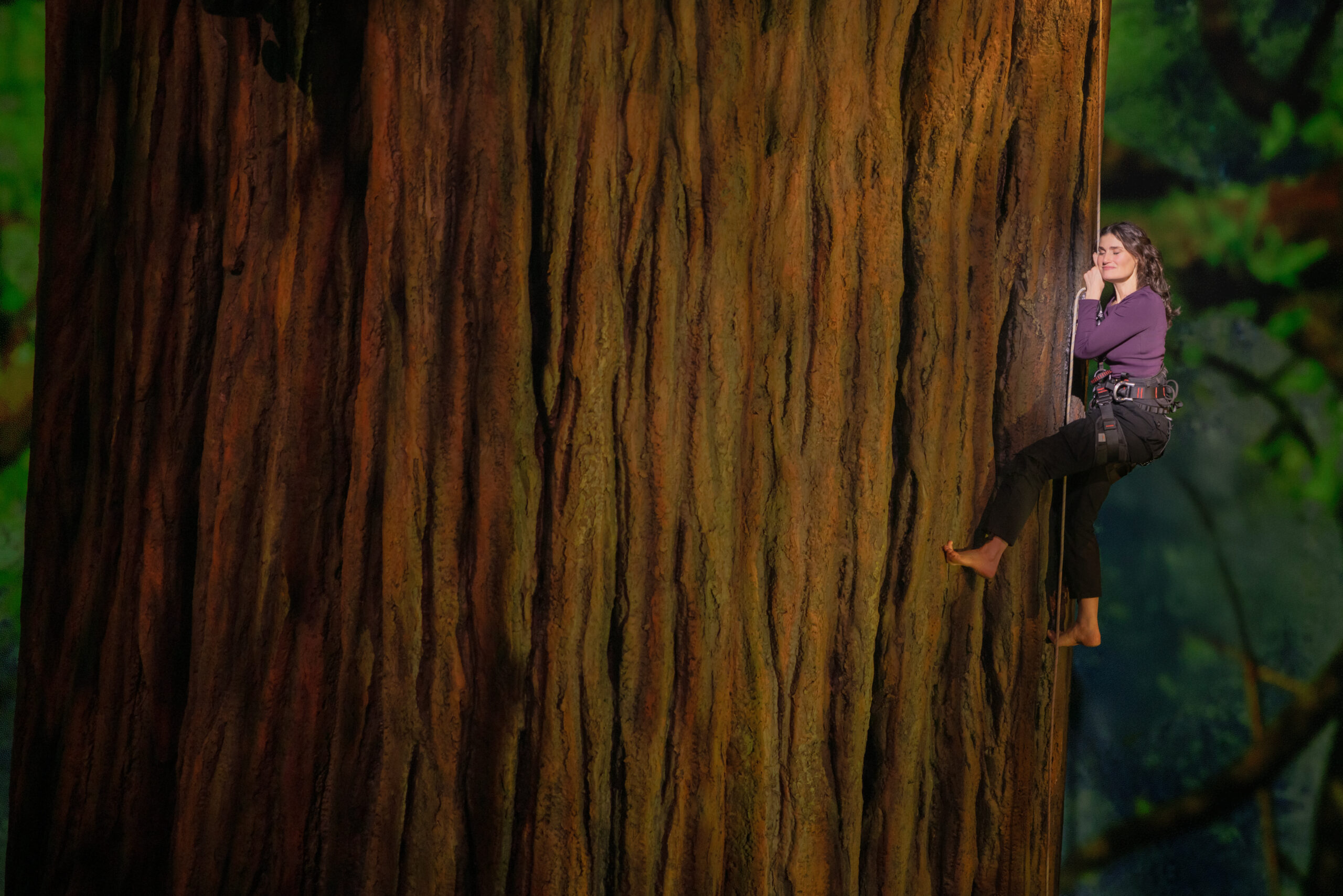

In “Redwood,” Menzel plays Jesse, a queer Jewish woman in the throes of grief. Her son Spencer, played by Hapa Jewish actor Zachary Noah Piser in a stand-out performance, died from an accidental overdose nearly a year ago. As the anniversary approaches, Jesse can’t take it anymore. She leaves her wife Mel (De’Adre Aziza) and drives across the country to Eureka, California, where she stumbles upon a redwood forest. Thanks to two canopy researchers, Finn (Michael Park) and Becca (Khaila Wilcoxon), Jesse has the opportunity to climb one of the trees. It is in the canopy of the redwoods and the branches of Stella, the name Jesse gives the tree, that she finds, for the first time in nearly a year, solace.

She communes with nature, dancing and singing in the trees and wrestles with her demons all in the majesty of the Redwood. It’s in Stella’s canopy, too, that Jesse learns about the Jewish concepts of tikkun olam, healing the world and bal taschit, the prohibition in the Torah against wanton destruction that is also often interpreted as a decree against needless waste. Earlier in the show, we learn that Jesse is Jewish thanks to lyrics in the song “Climb”: “I can hold a tree pose. I can do a downward dog, / ’cause I did yoga once at my old synagogue.” But it’s through Becca, who is proudly Black and Jewish, that Jesse learns about these ancient concepts. Becca shares that she is driven to conservationism because of her Jewishness — at 10 years old she lost her home in a wildfire and found comfort and purpose in tikkun olam. She sings: “Working hard to save the trees / Is my responsibility / I know what I must do / I gotta leave the world better than the one I came into.”

Though Jesse initially pushes back against Becca’s lesson, telling her that repair is not always possible, Jesse later experiences a wildfire while in Stella’s branches. This moment causes her to finally face the memory of her son and understand that healing is both possible and cannot be done alone.

From an audience member’s perspective, as the show goes on, the catharsis happening around me was palpable. Almost like the recitation of the viddui, the collective confession on Yom Kippur, everyone was simultaneously having their own private moment with the show and was emotionally connected to the people around them. This emotional resonance in “Redwood” obviously doesn’t occur just because of the Jewish values that anchor the show. But in highlighting tikkun olam and bal taschit, the discussion of the those concepts in the havruta-like pairing of Jesse and Becca and, notably, what might be the first Black and Jewish original character on a Broadway stage in Becca, “Redwood” finds its authentic spark.

Menzel first had the idea that would become “Redwood” years ago and then co-conceived of the musical with Jewish playwright Tina Landau. It took the pandemic for the project to find its legs, but eventually Landau wrote the book and co-wrote the lyrics with composer Kate Diaz. Completely by coincidence, the show opened on Tu Bishvat 5785.

And it is through this sequence of events that I find myself on a Zoom call with the Idina Menzel talking about spirituality, of all things. But, weirdly enough, talking around the concept of God with one of the most talented Jewish actresses of a generation is quite a down-to-earth experience. When I ask Menzel why it was important to her and Landau to ground the show in tikkun olam and bal taschit, she’s open that these ideas are relatively new to her. “Idina, me and Jesse, my character, are sort of both learning a lot through this story,” she says. “I’ll be humble and say I didn’t know a lot of these… what would you call them?”

I was wholly unprepared for Idina Menzel to be asking me questions, but I offer the term “values.” She thinks aloud, too, bouncing the word “constructs” and the phrase “Jewish mysticism” off of me. We land somewhere in the middle of all three. “Tina introduced them to me, and I just think they’re so beautiful in [the show],” she continues. “We wanted the story to be about how people cope with adversity, pain, how they choose to repair, when they choose to repair, if they ever choose to repair… if they try to escape these things, or if they choose to hold them in their hearts and allow that to spur them on and to live a richer, deeper life.”

In spite of not being, in her owns words, “a terribly religious person,” Menzel affirms that she is “very attached to my Jewish tradition and culture.” The great-grandchild of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants, Menzel grew up on Long Island. She idolized Barbra Streisand as a teen and began her professional career at 16, singing at weddings and b-mitzvahs in the tristate area — though Menzel didn’t have her own bat mitzvah. (She also didn’t grow up celebrating Tu Bishvat, despite her love of trees.) Almost inevitably, part of Menzel’s Jewish culture has shone through her weighty career.

While she’s best known as Maureen Johnson in “Rent,” Elphaba Thropp in “Wicked” and Elsa in “Frozen,” Menzel has also played Dinah Ratner in “Uncut Gems” and Bree Friedman in “You Are So Not Invited to My Bat Mitzvah,” collaborating time and again with Adam Sandler. She also included Jewish songs on her 2019 holiday album. The 11th track, “Walker’s 3rd Hanukkah,” is a simple recording of Menzel singing the Hanukkah blessings, with her then 3-year-old son Walker, whom she shared with ex-husband and former “Rent” co-star Taye Diggs, imitating the Hebrew prayers back to her.

At one point in our conversation, I’m blathering on about how much I loved the character of Becca and how important it is for audiences to see that Black Jews exist. “Like my son,” Menzel smiles. I ask if he’s seen the show and she nods. “He’s really proud. He’s proud of me. He’s proud of the process and all the work that went into it,” she says. “And he gets it on a deep level.”

Surely part of that understanding stems from the experience Idina’s family had during the devastating L.A. wildfires in January. While Menzel was in tech for “Redwood” in New York, dry conditions and the fierce Santa Ana winds caused multiple wildfires to ravage Southern California, killing at least 30 and destroying nearly 16,000 homes. Initially, Menzel’s home, where her husband Aaron Lohr and her son were staying wasn’t close to the fire. But as it continued to burn uncontained, they eventually had to evacuate for two days. No amount of training with “vertical performance” dance company Bandaloop or actually scaling a real redwood with a licensed climber and singing reverberating songs through the redwood forest — things Menzel actually did in preparation for the show — prepared her for this too-close-to-home moment. “I was [in New York] and had no control of anything, and I just wanted to get them out of there. And I was trying to put on the show and memorize lines and…” she winces slightly. Menzel counts herself as very lucky. But immediately afterwards, the “Redwood” team had to assess on how to proceed.

“There was a worry of: Is this going to be too raw for people now? Is this the wrong time now?” Menzel, who was mourning alongside friends who lost their homes, reflects. “But also we realize that when you have a new original musical, that’s fresh and modern and of its time, things are going to happen all the time that parallel what’s going on in the world.” Ultimately, the team did some rewriting to make sure there was a palpable sense of security in Stella’s canopy, and it seems to have paid off. Menzel tells me that people have come to see “Redwood” who have lost their homes who found the show to be healing. “It seems like people have found peace in it through the show,” she says.

Menzel has previously spoken about struggling with self-deprecation as a performer, and it’s on full display when we talk about what else she hopes audiences will take from the show or what impact she hopes Jesse will leave on Broadway. She tells me its hard for her to pat herself on the back and be presumptuous about what others will take away from the show. But when she gives herself a little leeway, Menzel points to the heartwood. As viewers learn in the show, the innermost part of a redwood tree is called the heartwood. Even though it’s technically dead, it’s the strongest part of the tree. “I would hope that people would embrace their heartwood,” she says. “I think it’s that embracing of the things we’ve lost in our lives that can actually give us rebirth and resilience and a reason to live again.”

As for herself, Menzel is certain that she will be able to carry this show with her, and the Jewish values-constructs-mysticism she’s learned because of it, forever. It’s clear this is indeed the case as we wrap up our conversation. I ask her about where she finds meaning in Jewishness in her daily life and her answer is like a sapling, brought forth from ancient roots, expressed into the bright world anew.

“It’s family. I think it’s just resilience,” she says. “It’s literally like the trees. It’s knowing that throughout history we’ve withstood so much, and we are survivors. The trees — the redwoods — fire actually helps them open their seeds and disperse their seeds and grow new life. I feel like that’s been our experience as Jewish people for thousands of years, is to support one another. To be fighters and survivors, to find meaning and to always bring the light out of the darkness.”

It’s a lofty, gorgeous, spiritual note to end. I’m about to say goodbye when she poses one more unexpected question to me, and in doing so, she adds her perfectly Jewish inflection to the note she just hit. “Am I going to sound like a bad Jew in this piece?” she asks. I tell her she definitely won’t. Like a slow rappel down the sides of a redwood tree, we softly land on earth once more.