Witches have taken on many forms in contemporary popular culture: They might look like Hermione Granger, Sabrina, or the ‘90s icons in The Craft. But, of course, the mother of all witches is the cackling, potion-brewing, broom-riding crone-archetype that we see every year around Halloween.

The witch is the female icon of spookiness, descended from centuries of various stereotypes, images, and beliefs from medieval and early modern Western and Northern European cultures. In those days, witches, primarily believed to be female, were thought to have pacts with the Devil, commit acts of beastiality, and have an appetite for newborn babies.

But these slanderous stereotypes were not only reserved for women. In fact, such cultural images are derived from a long tradition of demonizing societal “others” — including, of course, Jews.

Let’s dig into the spookily antisemitic history of witches and witchcraft, shall we?

You might already be familiar with the history of violent misogyny that fueled the persecution of “witches” in the United States — i.e. the Salem witch hysteria and consequent trials during the 1690s. You might also be familiar with the centuries-long history of ongoing witch hunts in early modern Europe, which most scholars agree began with the widespread persecution of heresy during the medieval Inquisition and continued up until the 18th century. Misogyny was undeniably a major motive for the execution of somewhere between 40,000 and 100,000 people across three centuries of witch hunting in Europe. The majority of those accused of witchcraft during this time were women — around 75% to 85%.

However, the popular construction of female witches as we think of them today didn’t truly pick up until the European “witch craze”, which took place from approximately 1450 to 1750, according to history scholars Lara Apps and Andrew Gow. Prior to that, “witch” was a catch-all term that referred to a wide variety of accused heretics or generally non-conforming “others” in Christian European society, such as Jews. European constructions of the witch actually come from a long line of myths about “Jewish ‘heresy’ and the nature of its persecution,” notes Yvonne Owens, a professor of Art History and Critical Studies at the Victoria College of Art.

This explains why many Christian superstitions about Jews in early modern Europe sound a lot like characteristics associated with witches. For example, that familiar pointed, black witch hat may have a unique relationship to Jewish history. After around 1215, Jews were required to wear a distinguishing cone-shaped judenhut, which soon made Jews visible targets for antisemitism. So closely were Jews associated with Satanic threats that a law was passed in 1431 in Hungary requiring those accused of sorcery to wear “peaked Jew caps.”

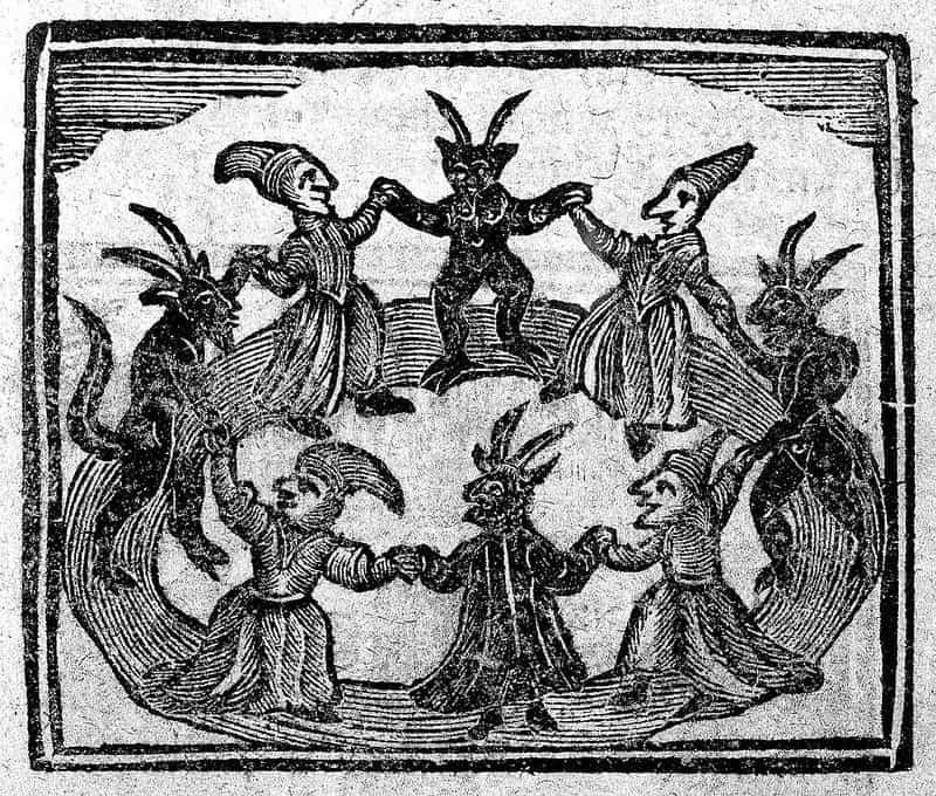

Shabbat was also wrapped up in early modern narratives of witchcraft — specifically, the notion of the “witches’ Sabbath,” which referred to the nighttime gatherings of witches during which sorcery and Satanic rituals supposedly took place. In early modern times, non-Christian gatherings or meetings of any kind were automatically seen as anti-Christian and therefore threatening, Satanic, and heretical, and usually involving sexual orgies, according to Lily Clemenhaga. The weekly Jewish Sabbath is of course a ritualistic practice existing outside the Christian norm, and therefore it was automatically associated with heresy and Devil worship in medieval Europe.

The term “synagogue” was even used during the 12th century by medieval writer Walter Map to refer to the meeting place of any kind of heretical communion. By the 15th century, the term “synagogue” was replaced by “Sabbath” within the church’s popular rhetoric, Clemenhaga writes. This antisemetic rhetoric around Shabbat and other Jewish worship practices, Clemenhaga points out, laid the groundwork for the concept of the “witches’ Sabbath,” an idea that was later popularized during the “witch craze.”

On top of accusations of orgies in the synagogue, Jews were also frequently depicted with physical features associated with the Devil, such as claw feet, talons, and horns: You may have heard of the absolutely bonkers myth that Jews have “horns under their curls” (this is actually believed to originate from the Biblical depiction of Moses sporting some cute lil’ horns).

The depiction of people with animalistic, demonic qualitites wasn’t just unique to the Jews: anyone outside the societal Christian norms were frequently depicted as having Satanic or demon-like qualities. Nonetheless, classications of witches and Jews were very closely related in medieval and early modern Europe. And that might be due to the fact the actual physical anatomy of both Jews and women were classified under the same medieval medical categories.

The medieval medical system of the four humors/tempraments served as the foundation for superstitions against both Jews and women. As Yvonne Owens points out, Jews and women were both believed to be inhernetly melancholic, phlegmatic, and made up of “putrid black blood,” and were thought to be ruled by the planet Saturn. Hence, Jews, like women, were considered to be passive, inferior, polluted, and untrustworthy. Due to these inherent humoristic and temperamental qualities, it was believed Jews and witches were more likely to veer towards Satanism and commit demonic acts such as cannibalism, infanticide, holding communion with demons and the Devil, and taking flight at night. These behaviors, originating from Jews’ and women’s supposed “putrid black blood,” would later come to be closely affiliated with ideas of witchcraft.

So, how did all these myths about Jews, witches, and other heretics boil down to create the iconic Halloween witch herself? Some scholars credit the printing press with the creation and spread of the Western witch archetype as we know it. After its invention in 1440 (remember, the “witch craze” was kicked off only 10 years prior), the simplified image of the female witch, herself an amalgamation of centuries of beliefs and classifications of Jews and other kinds of heretics, was printed and rapidly circulated across Europe and later within the United States. As a result, the printed image of the old, ugly female witch flying on broomsticks and donning a black peaked cap and gown became cemented into the Euro-Christian imagination, and lives on in American Halloween traditions today.

The intertwining history of the demonization and persecution of Jews, women, and other heretics in European societies is complex, contested, and vast. Indeed, the relationship between the witch archetype and antisemitism has many possible origins, histories, and understandings. However, it appears that medieval Jews and witches did indeed share a common struggle: the struggle of being othered, demonized, and persecuted based on Christian superstition, mythologization, and stereotyping.

So, be right back, just gonna honor my ancestors and go make some matzah ball soup with baby’s blood before I take off on my broomstick, cackling hava nagila in the light of the full moon.

Header image from “Witches at a Sabbath, The History of Witches and Wizards,” England, 1720, Public Domain Review.