In my introductory sociology class, I learned that language is a vital and inseparable element of any culture, fostering a sense of communal identity and profoundly shaping cultural traditions. This principle elucidates why a near-universal element of colonization is stripping native people of their cultures and the forced universalization of the colonizer’s language.

The Bukharian Jews, like other Jewish groups across the world, were minorities in countries that underwent countless conquests and regime changes over the centuries; like other Jewish groups, they learned to adapt to their host countries’ cultures while still retaining their distinctly Jewish identities. The Bukharian language — Bukhori, or Judeo-Tajik — could not be more emblematic of this delicate balance, fusing elements of Hebrew, Persian and Tajik.

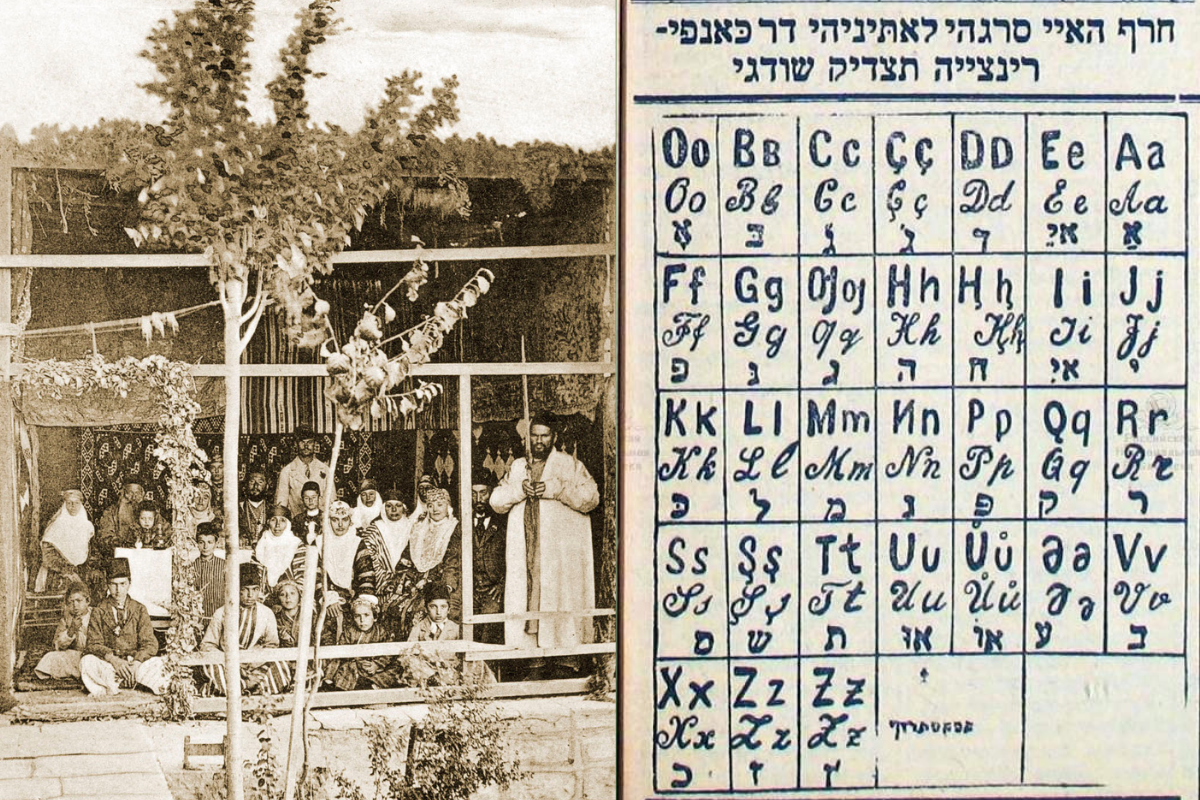

For most of my life, I had assumed that the Bukharian language was purely a spoken one, perhaps a sort of villagers’ dialect for Jews living in secluded communal enclaves. But upon accidentally coming across the archives of Rahamim, an early-20th-century newspaper written in Bukhori, I began to question my preconceptions. To my surprise, the newspapers were not printed using Latin or Cyrillic script — rather, in the signature fashion of other Jewish languages, they used Hebrew lettering. Upon doing further research, I learned that the development of Bukhori into a literary language can be attributed to Rabbi Shimon Hakham, who founded Jerusalem’s Bukharian quarter in the late-19th century and first translated numerous sacred texts into Bukhori.

Though I felt deeply inspired by the sight of the newspapers, it quickly hit me that I was unable to read a word of them, effectively preventing me from accessing any historical or cultural insight they might have contained. Indeed, I anticipate that only a few thousand individuals possess the ability to read this version of Bukhori, as it requires a rare and dwindling dual skill set: total fluency in Bukhori and total proficiency in Hebrew script. Only a few minutes after coming upon the newspapers, I closed the archives struck by a real sense of loss.

Growing up as an American-born Bukharian Jew, my primary exposure to Bukhori was through my grandmother. Despite her upbringing in Soviet-controlled Uzbekistan, she always reverted to Bukhori while on the phone with her sisters, venting her frustrations or recounting her triumphs in her native tongue rather than in the Russian she had been educated in. My parents, belonging to a significantly more Russified generation of Soviet-born Bukharians, can only somewhat understand Bukhori. And I, a member of the first generation of Bukharians born in America, cannot speak or understand Bukhori at all.

In this sense, I am far from alone among Bukharian Jewish youth, who are currently splintered between America and Israel. While virtually all of our grandparents grew up speaking Bukhori at home, only a select few youth who were raised by their grandparents can understand the language today, and fewer still are able to speak it well enough to pass it onto their children. In short, the Bukharian language is slowly dying, and while documentation efforts are well underway, it would be senseless to fantasize about any spoken revival of the language after my grandparents’ generation draws its last breath.

Acknowledging Bukhori’s inevitable decline is difficult, but it brings forth a pressing question: If language is supposed to serve as the cohesive force binding a culture, what lies ahead for the Bukharian community? How are we to preserve our heritage and traditions without a unique common tongue?

So far, we have found a temporary alternative. As Bukhori continues to fade from our vernacular, most younger Bukharian Jews in America remain linguistically united by a shared usage of the Russian language speckled with Bukhori interjections and inflections. But even this shared language is slipping from us, especially as a new generation with American-born parents emerges, likely to only speak English.

Our numbers are few and our culture is beautiful, far too precious to exist exclusively in academic archives scattered in dusty corners of the internet. Still, I cannot help but wonder whether the loss of Bukhori signifies the beginning of the end for the Bukharian community, a defining step towards total cultural homogeneity with the average American. I can only hope that despite what I learned in sociology class, there’s a fighting chance for our long-term cultural continuity beyond our shared lingual identity.

Though I was initially daunted by the thought of maintaining such lasting cultural endurance, I eventually realized that I did not need to look far to find a successful example — the Ashkenazi American Jewish community, which has resided in America for approximately a century longer than Bukharian Jews have, still retains a distinct cultural identity despite Yiddish not being its primary spoken language. While we do not need to mimic Ashkenazim, we can learn from certain initiatives taken by fellow Jews to keep traditional cultural elements intact while also forging a modern, revitalized Jewish culture for a new country.

By fostering intergenerational connections with our elders, we as Bukharian Jewish youth can take concrete steps to ensure that our heritage remains vibrant and accessible to future generations. In many ways, I believe that we are already doing so by hosting Bukharian community events without the help of our parents — our success is a matter of remaining steadfast in our efforts and our ability to pass this zeal onto the next generations.

Picture this: The scent of traditional Bukharian dishes like osh plov and bakhsh fills the air. The rhythms of the doira pulse through the room while teenagers join their parents in twisting their arms in the classic Bukharian dance style, donning the joma, our traditional ceremonial robe. Such community-building events are already in full swing, and it’s our responsibility as youth to sustain them. While uncertainties will remain omnipresent as the threat of cultural assimilation looms large, our determination can pave the way for our continuity, no matter what language we do it in.