Typically, when American Jews advocate for reparations for slavery, we base our argument in our community’s experience of receiving reparations following the Holocaust. But the Jewish case for reparations dates back much further than the Holocaust; it’s in our Torah, including in the iconic story of Passover.

If you’re like me, this may come as a surprise. My memory of the Passover story (admittedly informed predominantly by DreamWorks’ The Prince of Egypt and foggy memories of childhood Hebrew school) definitely did not include reparations paid by the Egyptians for the Israelite’s 430 years of slave labor. But it’s right there in our Torah.

So, what does the Torah say about reparations, and how does it apply to modern times? Let’s break it down.

First, what exactly are reparations?

In 2021, reparations are often discussed in financial terms. This is largely appropriate, as the offenses necessitating reparations are crimes that often steal a peoples’ labor, land, and always their liberty. In the case of the enslavement of Africans, the ensuing legal segregation (Jim Crow), and ongoing brutality and discrimination toward Black Americans, this can be put in financial terms to the tune of between 10 to 12 trillion US dollars.

However, in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ transformative essay, “The Case for Reparations,” he is clear on a more comprehensive definition:

Reparations — by which I mean the full acceptance of our collective biography and its consequences — is the price we must pay to see ourselves squarely … What I’m talking about is more than recompense for past injustices — more than a handout, a payoff, hush money, or a reluctant bribe. What I’m talking about is a national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal.

Reparations are not merely a stimulus check. Coates is clear: “What is needed is a healing of the American psyche and the banishment of white guilt” as we grapple with the unfinished business of fulfilling America’s promise to enslaved Africans and their descendants.

So, you say reparations are mentioned in our Torah?

Yup, in at least three of the five books:

Exodus 3:19-22

… I will stretch out My hand and smite Egypt with various wonders which I will work upon them; after that he shall let you go. And I will dispose the Egyptians favorably toward this people, so that when you go, you will not go away empty-handed. Each woman shall ask of her neighbor and the lodger in her house objects of silver and gold, and clothing, and you shall put these on your sons and daughters, thus stripping the Egyptians.”

Women asking of their neighbor “objects of silver and gold” fits the bill of financial reparations, but admittedly lacks the reckoning Coates calls for. Regardless, it’s commanded by God here and elsewhere throughout the first, middle, and last book of Torah as a necessary component of liberation:

Genesis 15:13-14

And He [God] said to Abram, “Know well that your offspring shall be strangers in a land not theirs, and they shall be enslaved and oppressed four hundred years; but I will execute judgment on the nation they shall serve, and in the end they shall go free with great wealth.”

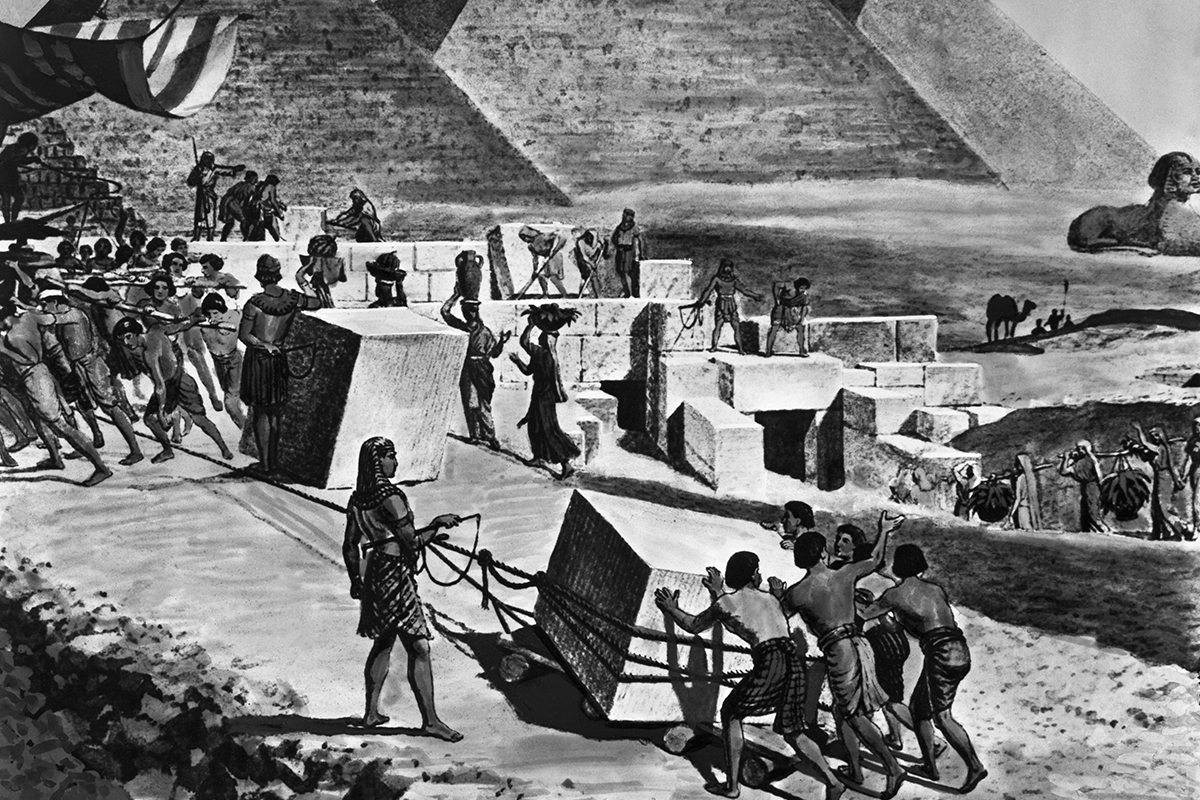

As you can see, this was not a one-off comment from God to Moses in a moment of excitement at the burning bush. God’s intent from the first book of the Torah, Genesis, is to ensure that the Hebrews are monetarily compensated following enslavement (though the Israelites were of course not aware of this fact while they were forced to work on behalf of the ancient Egyptians). These are not the only examples of the Jews’ repayment for their 430 years of unpaid labor in the Torah (or Talmud actually), but for the sake of my word count I recommend you read this excellent and thorough piece by Rabbi Aryeh Bernstein entitled The Torah Case for Reparations.

If the connections Rabbi Bernstein and I make aren’t sufficiently compelling, it may interest you that Coates’ “The Case for Reparations” opens with a quote from the last book of Torah as well (Deuteronomy 15: 12–15).

It’s important to say that, as someone who works for a reproductive health and rights organization, I’m the last person to advocate for policy change on the basis of interpretations of ancient religious documents. (Really!) However, I do find it deeply important to understand what our most essential religious texts say on the matter to inform our community’s stance.

Why is this an issue for white American Jews? Or, more commonly phrased as: “My family hadn’t immigrated to the United States at this time, so why should I be implicated in the fight for reparations?”

Well, two reasons. First, while most Jews and your relatives personally may not have found their way to the United States in this period, that is not to say that there were no Jewish people involved in the slave trade. (And no, I’m not about to make the extremely antisemetic claim that Jews “controlled” or played a major role in the slave trade. That’s been debunked many times and I can’t believe people still go there.) However, we cannot deny that a small number of members of our community did indeed engage in — and profit from — the trade of enslaved people. For one, the Lehman brothers.

Now, there are tremendous issues with holding an entire community accountable for the actions of a few members. That is indeed one of the tenants of how white supremacy functions: lumping all members of a community together in such a way that the actions of a few inform an individual or society’s view of all who belong to that community. That’s not what we’re doing here.

I raise this particular claim because there is a specifically Jewish tradition of collective responsibility we hold ourselves personally accountable to. You participate every year if you go to synagogue for Yom Kippur. It’s the recitation of the Viddui:

We are not so brazen-faced / and stiff-necked / to say to you, / Adonoi, our God, and God of our ancestors, / “We are righteous and have not sinned.” / But, indeed, we and our ancestors have sinned.

The prayer goes on to list a number of chataim (transgressions) we collectively confess to and repent for as we beat our chests. As My Jewish Learning describes: “[The Viddui] is said in first-person plural, because while each individual may not have committed these specific sins, as a community we surely have, and our fates are intertwined.” It’s not “I have stolen” but “we have stolen.” And that “we” includes our ancestors.

This is our call to remedy the sin of members of our community, and our country.

Further, if we take the spirit of teshuvah, or repentance, to heart, do we not have an opportunity and an obligation to examine how our actions may have been anti-Black or otherwise harmful? Chattel slavery is long since past, but we must grapple with its effects, as well as ongoing behaviors such as discrimination and stigmatization that bear recognition and reparations.

What’s next?

It’s not the place of this article to dictate how reparations to Black and Afrian Americans could or should be explored and rendered; there are smarter people in this fight who have been in it longer than I have, and you should check them out. I’ll list a few here to this end: N’COBRA, NAARC, the team at NPR’s CodeSwitch who did a very nuanced podcast on the topic, and many more.

What I am arguing is that non-Black American Jewish communities see this issue for what it is: an issue we must lend our voices to, including in support of H.R. 40. There’s precedent for it in the Jewish community and besides, America has tried reparations before. Why not for Black and African Americans? We must be rigorous in pursuit of justice, as the Torah commands. On Passover — and every day — it is not enough to celebrate our freedom while others have not been granted freedom in the way God commanded it. Lo dayenu.

I am extremely grateful to the many thought leaders whose work I relied upon in writing this article; namely Ta-Nehisi Coates, Rabbi Aryeh Bernstein, and MyJewishLearning.com, and Pre-Passover Reparations Cohort at GatherDC. Thank you especially to Rabbi Ilana Zietman, for planting the seed, sending me many (if not most) of the sources, and all of her invaluable wisdom.