At the start of the pandemic, I found myself back in my parents’ house, stressed and sad. It was not my childhood bedroom — they moved when I left for college — but I had meticulously transferred all my books from the bedroom I grew up in to this new, unfamiliar bookshelf. While plenty got donated, I was unable to part with some, including my well-worn copy of The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster.

So, in early March 2020, I found myself pulled back into the Kingdom of Wisdom, following the adventures of a boy named Milo and Tock, the “watch” dog, come to life by Juster’s magical writing filled with wordplay and puns. Growing up, The Phantom Tollbooth was everything to me. It’s one of those formative books in my life, and returning to it was like a cozy, warm hug. Even amidst the chaos of the early days of the pandemic, the transition to remote work, and the fear of the spreading virus, The Phantom Tollbooth was there to remind me it would all be okay.

Though clearly intended for children, returning to Juster’s writing as an adult is still wondrous and relevant. “Whether or not you find your own way, you’re bound to find some way. If you happen to find my way, please return it, as it was lost years ago. I imagine by now it’s quite rusty.” Every sentence, every plot point, has meaning layered upon meaning, often found right there in the names of characters and places: the princesses of Rhyme and Reason, the Sea of Knowledge, the Doldrums, and so much more.

This is the legacy that Juster, who passed away on March 8, 2021, at the age of 91, leaves behind.

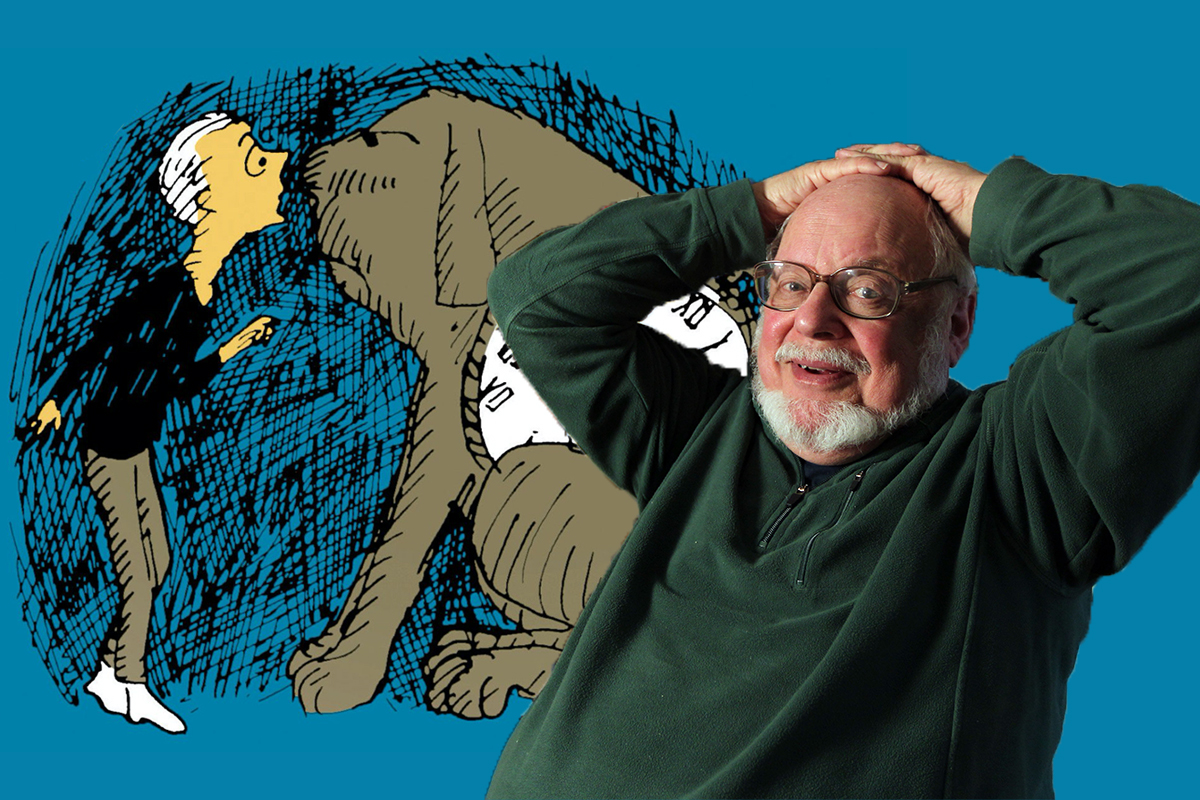

“His singular quality was being mischievous,” Jules Feiffer, who illustrated The Phantom Tollbooth, said in a statement. “He saw humor as turning everything on its head. It’s incredible the effect he had on millions of readers who turned The Phantom Tollbooth into something of a cult or a religion.”

Speaking of religion, while I didn’t know it when I first fell in love with his words, Juster was Jewish. “I define myself as a culinary Jew. I am a great cook. One of my favorite breakfasts is matzoh brei. I take great pleasure in making chicken soup,” he told Moment Magazine. (Norton Juster, I also love matzah brei, and reading this quote as I write this made me quite emotional.)

Born to a Jewish family in Brooklyn, New York in 1929, Juster studied architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. Juster’s elder brother was high-achieving, while he was more of a reluctant student. He followed both his brother and father into the world of architecture. After graduating, he spent time in the U.S. Navy, where he began to write. After leaving the Navy, he worked as an architect in New York, and taught architecture, design, and planning at Pratt Institute of New York and Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts.

One of the defining books of his childhood was reading I.J. Singer’s (the brother of Isaac Bashevis Singer) The Brothers Ashkenazi when he was 11 or 12. “I didn’t understand a word of what I read, but I read it all the way through. I had never heard language used like this.” His love of wordplay and puns comes directly from his father, a Jewish immigrant from Romania who worked as an architect in America. “He had a quiet, sly sense of humor. I’d sometimes walk into a room and he’d say, ‘Aha! I see you’re coming early since lately. You used to be behind before but now you’re first at last.’ Day after day he spoke this way. As a kid you don’t get it but later you do and you learn to control language in a very creative way,” Juster recalled.

He wrote The Phantom Tollbooth while procrastinating on another project. “The secret, at least in my life, is that if you want to do something you have to do something else to get away from that and that’s the thing that turns out to be worthwhile — whatever you’re doing to escape from doing what you’re supposed to be doing,” Juster said.

And I am so grateful he procrastinated his way to The Phantom Tollbooth, teaming up with cartoonist (and fellow Jew!) Jules Feiffer. Many of Juster’s ideas in the book were created just to challenge Feiffer to illustrate them, like The Triple Demons of Compromise (“one tall and thin, one short and fat, and the third exactly like the other two”). The two men remained friends their entire lives.

“I started thinking about it,” Juster said of the book, “and I came to the conclusion that this kid had gone into a world where everything was correct but nothing was right. That was a feeling I understood.”

For a little girl with a very active imagination — my sister and I were regularly spies, queens, train conductors, wizards, and anything and everything we dreamed of — The Phantom Tollbooth spoke to me on a deep level. I could dream that a cardboard tollbooth would appear in my room in the New York City suburbs, ready to whisk me away on a quest to reunite a kingdom. And while no such tollbooth ever actually appeared, it was Juster’s words themselves that allowed me that escape.

Back to those early pandemic days last March, surrounded by my childhood books in a grown-up version of my childhood room, I couldn’t have asked for a better escape than rereading The Phantom Tollbooth for the gazillionth time. Because while I was trying to do “everything correct” — wash my hands, don’t touch my face, avoid literally everybody in the world — absolutely nothing felt right. That is, except for Norton Juster’s silly words, and imaginative characters, and magical lands. May his memory be for a blessing. I know it’s already quite the blessing for me.

I’m off to re-read The Phantom Tollbooth and cry into some matzah brei.