Lately, when I can’t sleep, I lean into the experience. Insomnia is boring as well as infuriating, and it’s a comfort to transform those long predawn hours into something else entirely. So I usually find myself wandering around Boston’s cobblestoned streets until the sun rises and the air starts to get sticky with summer heat.

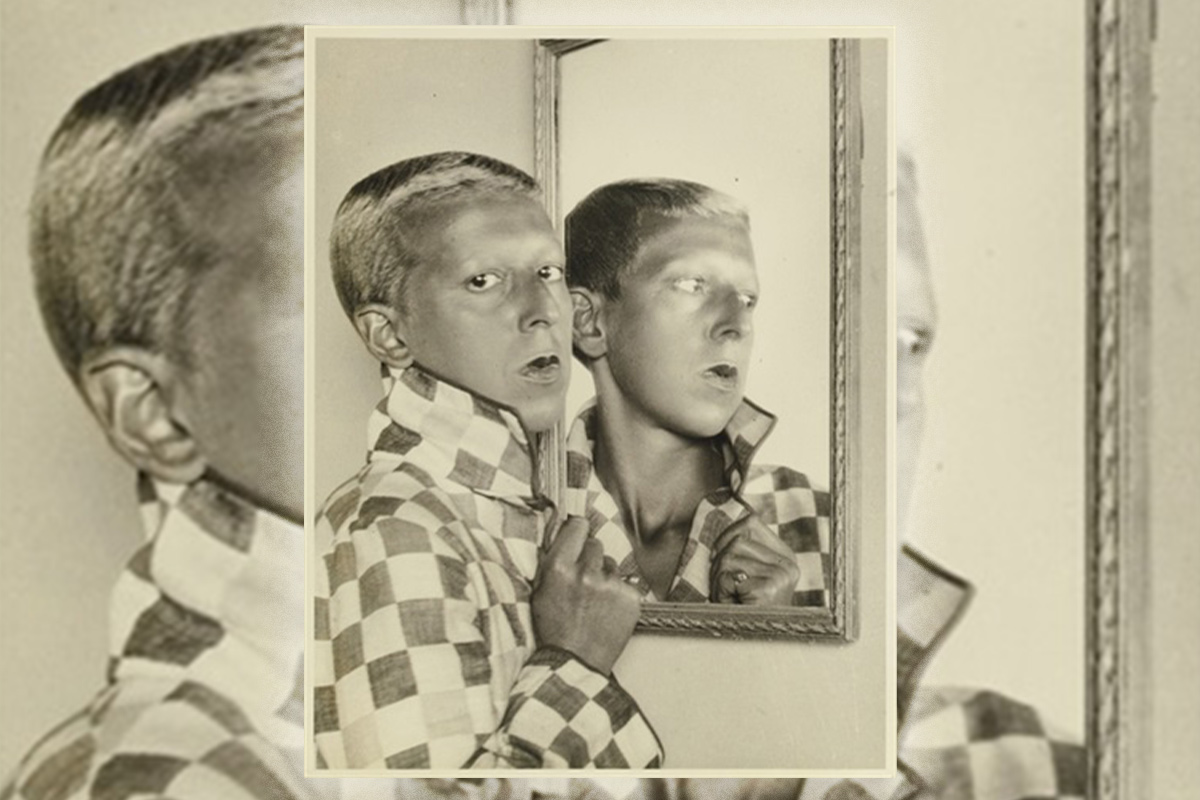

I was on my way back home from one of these walks when I happened to check Instagram and noticed a picture on my feed; I couldn’t tear my eyes away. Immediately, I was captivated by the figure’s sharp, convex nose, accentuated in equal measure by an angular jaw and a distinctive bald head.

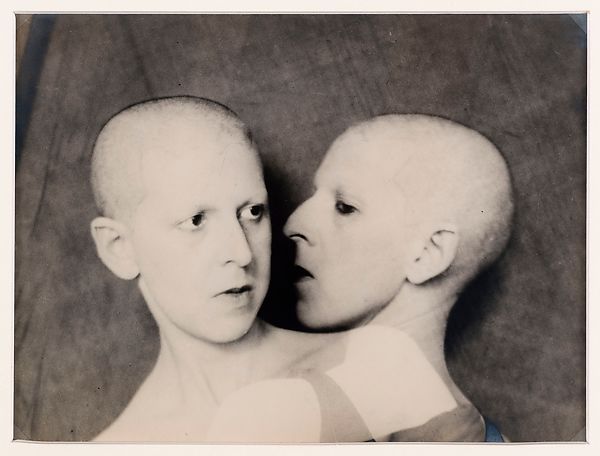

Gazing fixedly at me through the screen was the stark image of an ambiguously gendered person, in a composite photograph with two negatives printed at opposing angles. The person, whom I now know to be 20th century French artist Claude Cahun, positions her gentler profile in apparent retreat from her other advancing, seemingly predatory face. With her lips in a light pout, Cahun contemptuously directs her eyes downwards. The piece is titled “Que me veux-tu?” (“What do you want from me?”).

I could not help but feel an immediate kinship with Cahun. Even before I Googled her and learned that her birth name was originally Lucy Schwob, before she changed it to the gender-neutral Claude Cahun, I saw something intensely compelling in her work.

Born in 1894 in Nantes, France, Claude Cahun’s family background is more than a simple biographical note. Cahun’s father came from an established family of Jewish writers, but her mother was Christian and from an antisemitic family, the first of many binaries Cahun would go on to challenge during her life. Across numerous photographs, sculptures, various forms of writing, and eventually in anti-Nazi propaganda, Cahun tested the boundaries of gender and ethnic identities.

During World War II, Cahun and her partner, Marcel Moore, lived in Jersey, one of several islands off the coast of Normandy that was used as a training ground for new recruits under Nazi-occupied France. The queer couple systemically and artistically resisted Nazi occupation through political leaflets containing satirical sketches and anti-Nazi slogans, which the couple hid on German car windscreens, between pages of newspapers and sometimes, daringly, in soldiers’ pockets. While little of their anti-Nazi resistance art survived the decades, the scale of what Cahun and Moore achieved together is, ironically, best encapsulated by their trial before a Nazi court in 1944, in which the authorities were unable to believe that there were only two people behind the entirety of their self-organized, anti-fascist propaganda campaign.

Long before Claude Cahun turned to Surrealist art to resist fascism, she was already using photography as a means of self-determination. Never as publicly famous as her cishet Surrealist counterparts, like Pablo Picasso and René Magritte, Cahun was nonetheless well-known for her self-portraits, with André Breton once describing her as “one of the most curious spirits of our time.”

Her 1920s photographs were explorations of possible selfhoods, and she easily slipped between identities in her art, subtly challenging otherwise seemingly firm boundaries. In her posthumously published memoir “Disavowals,” Cahun confides, “under this mask, another mask. I will never finish removing all these faces.”

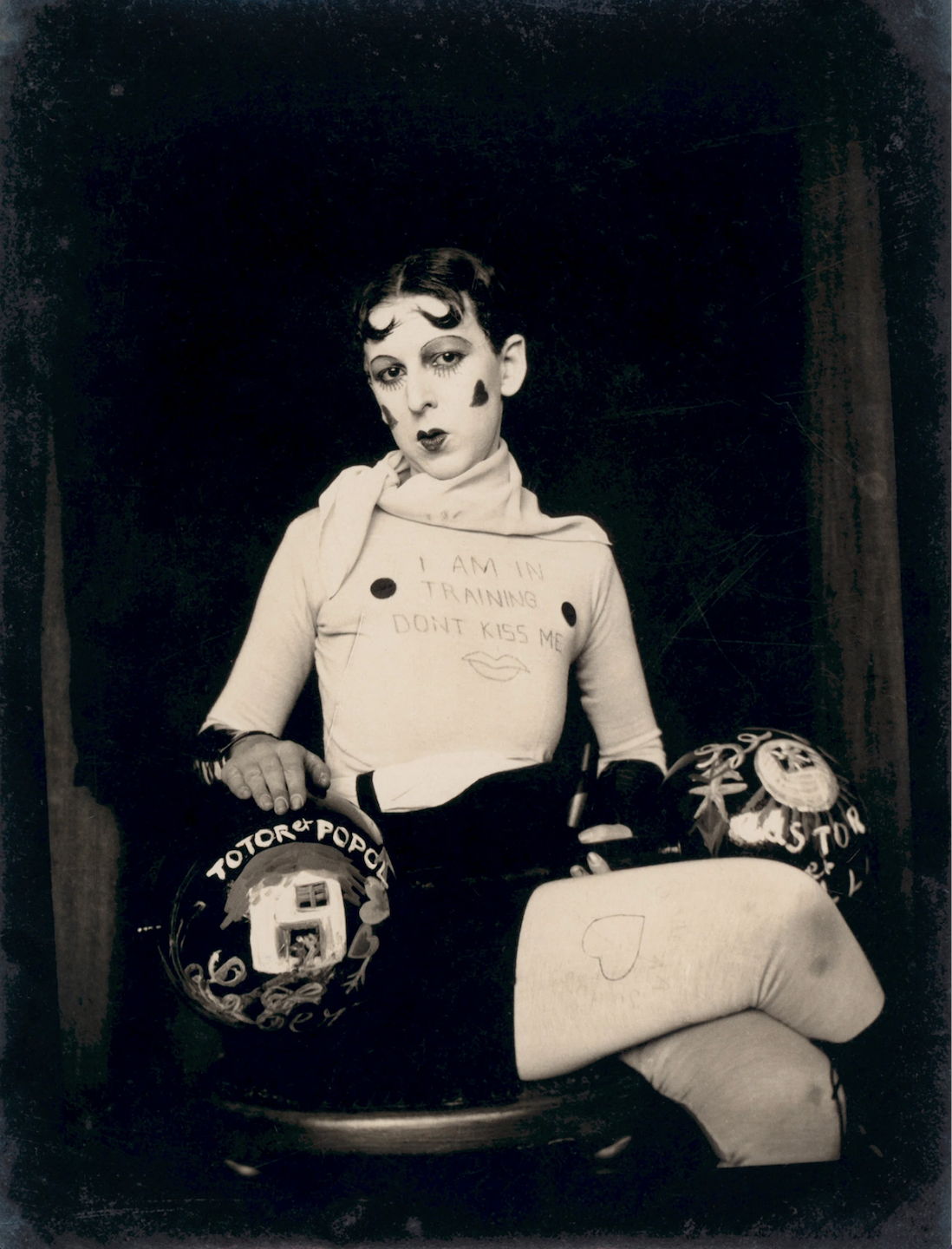

In perhaps one of her most visually arresting and reproduced images, Cahun adopts the persona of a slim bodybuilder. With slightly pursed lips darkened and glossy with lipstick, this version of Cahun meaningfully meets our eyes, seemingly daring the viewer to make a comment about her flat chest, which is adorned with the tantalizing message: “I am in training, don’t kiss me.”

Instead of focusing solely on gender and religion, Cahun’s art was a protest against the idea that categories of identity are purely determined by nature, rather than also culturally constructed. By shapeshifting categories across a series of self-portraits, Cahun can be seen as arguing for an external location for gender, sexual, and ethnic identities.

Cahun calls attention to the outward, visible factors which often shape identity: Her queerness is readily apparent, as is her recognizably “Jewish” nose. That nose was one of the first things that drew me to her image, and this was no accident. By using supposedly biological signs of a Jewish identity that was less a religious belief than a cultural identity to her, Cahun’s photograph registers her ambivalence toward classifications of identity, while still acknowledging the comfort of a label. In her images, she somehow also questions the very idea of a cohesive self.

Across numerous self-portraits, Cahun calls attention to the constructed nature of gender roles and identities. She uses external, visible factors to signal drag and the adoption of a variety of identities: a dandy, a vampiric parasite and even her own father.

“Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me,” Cahun wrote in “Disavowals,” before longingly concluding, “If it existed in our language no one would be able to see my thought’s vacillations.”

Yet Cahun is almost universally discussed as a lesbian and referred to unquestionably with she/her pronouns. The surface level nature of this approach avoids Cahun’s lifelong artistic and personal preoccupation with gender.

It’s impossible for me to separate my own gender feelings from Cahun’s, and there is really no right answer here. She lived in a different time, spoke a different language, and is not here to respond. But I am sure that Cahun would have taken great joy in the continued ambiguity surrounding her pronouns and gender identity: Even in death, she continues to destabilize supposedly fixed types.

Walking back though the tree-lined street towards my apartment, I continued to feel that I saw something of myself in Claude Cahun. Her adoption of various identities and gender performativity reminded me of the only reason I feel safe walking alone late at night. During those in-between moonlit hours, I look convincingly like a cisgender man. I first realized this one night when I was walking home from my (now) ex-girlfriend’s apartment and noticed a woman hurriedly crossing the street when she saw me approaching. She had the same darted backwards glances and hastened footsteps so familiar to me: She mistook me for one of the men I had just myself been walking quickly away from minutes before, another mask I find myself wearing.