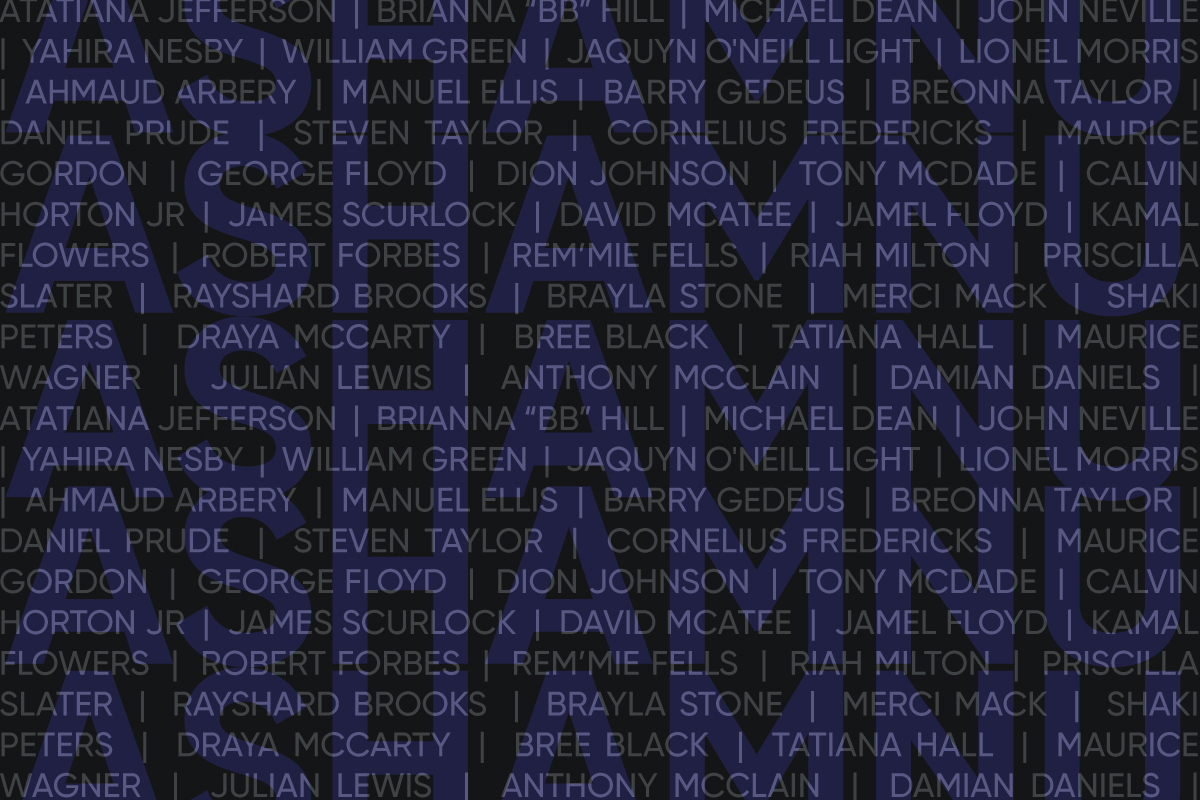

In the heat of my first Black Lives Matter protest, a prayer vigil at a local park, the names of Black people who had been murdered by police brutality were recited. It’s a long list of names I have tried to familiarize myself with, seemingly constantly expanding. In these moments, I have always wanted to punctuate each person, individualize lives by recognizing them as not just a drop in a sweeping wave of inequality, but a person who lived as I do but died prematurely at the hands of injustice.

Instinctually, the names called reminded me of a Jewish ritual for guilt: Ashamnu, the short confession of sins recited during Slichot and Yom Kippur services while congregants pound their chests in a collective form of atonement.

That day in the park, I struck my fist across my chest with each name, immortalizing each human being taken too soon.

When I was younger, I struggled with the Ashamnu prayer. At age 10, in synagogue striking my hand across my white Yom Kippur dress, I looked at the words of prayer and thought, well, I’m not guilty of most of that. While I wanted to devote the day to turn over a new leaf, I barely even understood the sins of moral corruption and adultery, never mind having committed such acts. Even as I got older, there are still sins that, at the end of the year, I’m pretty sure I have not committed. I soon learned that I was missing the entire point of the prayer.

The short confessions of the Ashamnu are said in the plural form: “We have trespassed, we have betrayed…” This choice to speak in the first person plural is because even if we are not personally fully culpable for such sins, our community is. With our own sins and inactions, we have created a community that allows for major violations to occur. We have to hold ourselves accountable for how we have been compliant in aiding the sins of another, and how our smaller sins can impact the standards of the broader community.

Tapping my chest at each name — “Eric Garner, John Crawford III, Michael Brown Jr…” — I know I must hold myself responsible, to feel the weight of each sin knowing that while it was not my actions that caused their death, my inaction is immoral, and my belonging to a society that has let this injustice go on for as long as it had means I am complicit. I can not lower myself in dignity and say, “I have murdered,” but I can and should acknowledge that we have.

As a white Jew, I have more work to do — on myself and for my community — so that I am not complicit in the murder of any more innocent people. I am not only responsible for my sins, but for my passivity in the sins of others, and for the world that I create when I, even minimally, contribute to more injustice and inequality. Each grief deserves to be punctuated with an exclamation point, a strike on the chest, and a reminder that if I — we — are liable for something, that also means we have the power to change it.

As we prepare for Yom Kippur, there is a plethora of guilt for which we can hold ourselves accountable. Emotional burn-out from the crossfire of social isolation and global turmoil has sent many of us reeling, too exhausted by the constantly piling pandemonium and its impact on our psyche to find a way to seek justice, only furthering our guilt. Solitude has deluded many to believe that they must hold the world on their shoulders, feeling a constant solitary responsibility to fix everything.

Ashamnu teaches us that we must all hold ourselves accountable — together. While this means we are culpable for the sins of others, it also means we are never meant to be alone in our efforts of making the world a better place. Striking my hand against my chest, I recognize how much work I have to repent and repair for injustice, and am alleviated by the fact that I am not in it alone.

Header image design by Grace Yagel. Names of those we lost in 5780 sourced from Say Every Name and Human Rights Campaign.