If you had joined me at the Met Museum on a recent Sunday, you would believe what they’re saying: New York is back. Though I’d reserved a ticket online (the Met’s COVID protocols include timed entry), I still found myself standing in a long line in the thick heat along with approximately five trillion other people before making it inside, where there were another five trillion people but also, thankfully, air conditioning.

The exhibit I’d come to see, “The New Woman Behind the Camera,” was worth the wait. A sprawling photography show, it features the work of women photographers taken worldwide between the 1920s and the 1950s. From street photography in Japan to desolate U.S. Depression-era scenes to glamorous fashion shots, the exhibition has ambitious aims: to present the often overlooked work of the so-called “New Woman of the 1920s,” whom they describe as “a global phenomenon that embodied an ideal of female empowerment based on real women making revolutionary changes in life and art.” Included in the exhibit were many new-to-me Jewish women photographers, including the first female war photojournalist to be killed during combat and several masters of street photography.

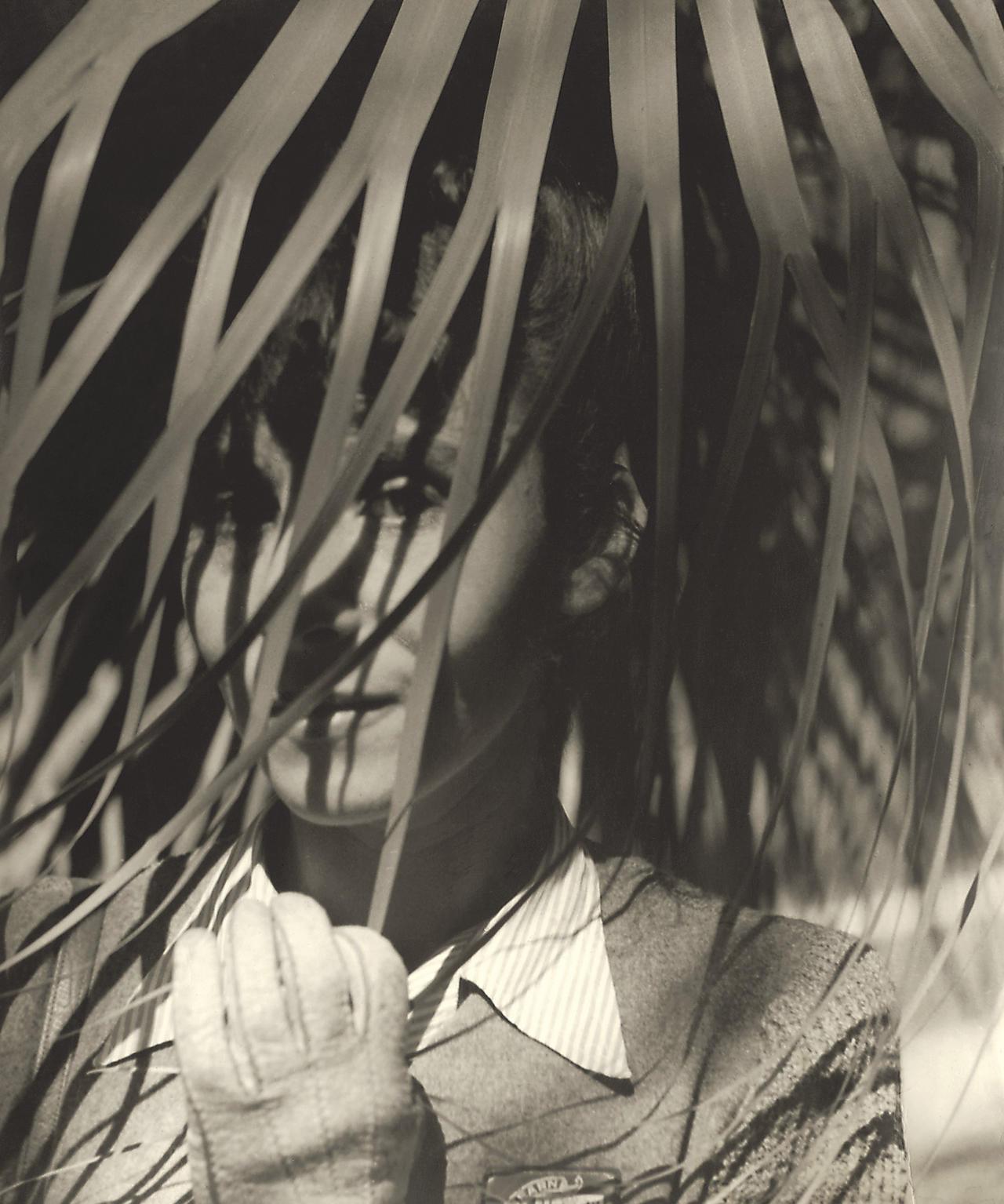

Jeanne Mandello, a German Jew living in exile in Uruguay, trained in Berlin and then opened a photography studio in Frankfurt. She took an experimental self-portrait in Montevideo in the early 1940s in which she gazes at the camera from beneath the leaves of a palm branch, her gloved hand ladylike, and her expression both inviting and enigmatic.

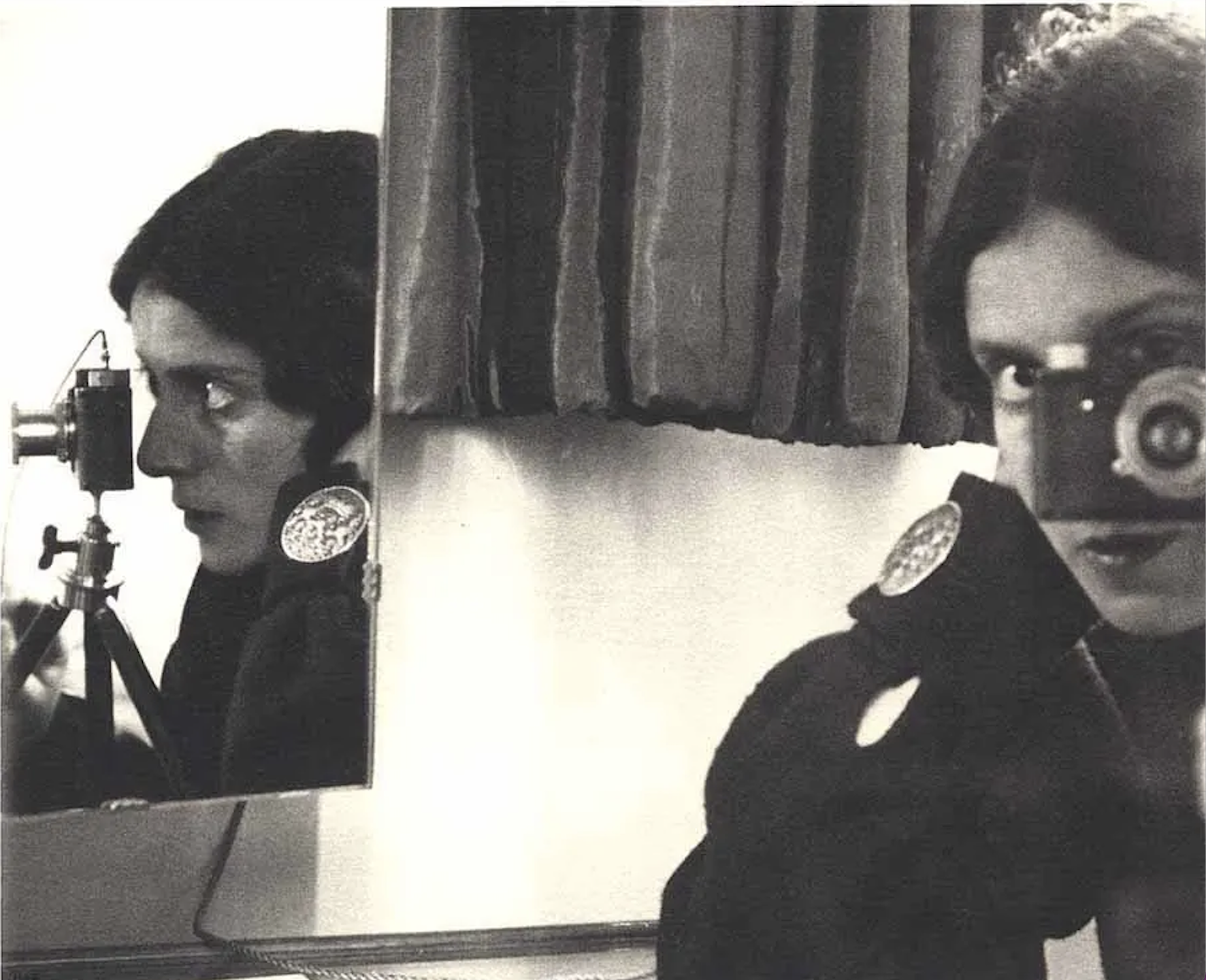

Ilse Bing, an American Jew born in Germany, began her career in 1929 and was one of the earliest photographers to embrace the Leica camera, a lightweight 35mm camera whose transportability transformed photography and inspired a surge in street photography and photojournalism. In 1930, Bing moved to Paris where she got her nickname, “the Queen of the Leica.” In this self-portrait, she uses mirrors and a striking composition to capture this quintessential image of the Woman Behind the Camera.

American Jewish photographer Rebecca Lepkoff made socially conscious work that often featured her Lower East Side neighborhood and its multiethnic residents. Her parents were Russian Jews who emigrated from Minsk to New York in 1910, and her photographs capture tenement life in the 1940s.

Helen Levitt, another American Jew, is known for her unromanticized street photography. She worked as a commercial photographer in the Bronx until the Leica camera allowed her to start exploring street photography in the 1930s. Cultural critic and poet David Levi Strauss has called her “a widely recognized modern master.” Her solo exhibition at the Met in 1992 was the museum’s first solo exhibition of a woman photographer.

Alice Brill grew up in São Paulo after fleeing Nazi Germany. (Her father died in a German concentration camp.) She left Brazil to study photography and returned in 1948. Her photography highlighted marginalized communities, like this photograph of an Afro-Brazilian woman selling goods on city steps in front of a busy street and cityscape.

Gertrude Fehr came from a prominent German Jewish family. She ran a portrait studio in Munich before escaping to Paris in 1933 after Hitler came to power. In Paris, she and her husband opened a photography school where she taught experimental exposure techniques (as seen in this luminescent photograph from 1936).

Liselotte Grschebina was born in Germany in 1908. In 1934, she emigrated to Mandatory Palestine and opened a photography studio in Tel Aviv. She was committed to the photography styles she learned in Weimar Germany: advocating for photography as its own unique artform, especially suited to capturing candid portraits.

Ilse Salberg was a German Jewish photographer who fled to Paris with her partner, the painter Anton Räderscheidt. The exhibition featured an extreme close-up of her partner’s underarm hair, which the photograph’s composition distorts into something strange and unfamiliar.

Gerda Taro was a German Jewish war photographer and antifascist activist who (like several others on this list) lived in Paris after escaping Nazi Germany. Her partner was the photographer Robert Capa, and much of her photography was credited to him. While documenting the Spanish Civil War in 1937, she was hit by a tank and died, becoming the first woman photographer to die in the field. Her affecting photographs of the frontlines and civilians appeared in several magazines.

Overall, the show’s selection is impressive and diverse, with sections on photography studios, avant-garde experimentation, fashion and advertising, social documentary, reportage and more. The exhibition explains this sweeping variety: “During this tumultuous period shaped by two world wars, women stood at the forefront of experimentation with the camera and produced invaluable visual testimony that reflects both their personal experiences and the extraordinary social and political transformations of the era.”

I found the curators’ understanding of the exhibit’s gendered terminology helpful: “Women constitute a heterogeneous group whose individual identities are defined by a host of variables and factors. Thus the designation ‘woman photographer’ is imperfect (as is the adjective ‘female’), yet it remains a useful framework for analysis.”

The show was not only heterogeneous, but so wide-ranging in sensibility, location and subject that it ran the risk of feeling barely curated, like a kind of highbrow vintage Instagram feed. Actually, that’s exactly what it felt like, and it was awesome. From war scenes to glamorous commercial photoshoots to indecipherable photos of the body, the photos captured work from many walks of life, countries and styles, and coalesced into a scattered exhibit that felt surprisingly contemporary.

As I left the museum, I found myself thinking about something the Jewish writer Nicole Krauss said in a 2017 interview I’d recently read: “Every writer is born into his or her material, whatever that may be.” This struck me as true for these photographers too, whose work was informed, if not defined, by the extraordinary times they were living in. I was inspired by their chutzpah. They captured what they saw and trusted it had value (or even if they didn’t trust it had value, they didn’t let that stop them). On the crowded steps of the Met, a young woman asked me to take a photo of her posing. I snapped a few options on her cell and then sanitized my hands, thinking about the insanity of the times we’re living in, too.

For a worldwide tour of women photographers from China to Spain to Hollywood, I highly recommend heading to the Met before October 3, 2021. And if you can’t make it in person, the virtual opening, which takes you through the exhibit in more detail, is available to view online.

“The New Woman Behind the Camera” is on display at the Met Fifth Avenue in New York from July 2-October 3, 2021.