Abbie Spector tore open a package from her grandfather one day in 2021. After months of keeping each other company long-distance during COVID by sending cookbooks and recipes back and forth between his home in Pennsylvania and her apartment in Detroit, and reviewing new recipes over the phone, he had sent her a final cookbook, marking the end of the ritual as their vaccines kicked in and their social lives picked up. The package contained, to Abbie’s initial horror, a yellowed and mildewing book whose cover read “THE WAY TO A MAN’S HEART… THE SETTLEMENT COOK BOOK.”

What Abbie found, on further investigation, was that the book was a hand-me-down from his own mother, Beatrice A. Spector, who had clearly put it to good use, based on the worn edges and abundant marginalia. And over the following two years of reading it, tinkering with recipes from it, and bonding with other inheritors of it, she learned the book was a wild ride through the psychology of early 20th century Jewish immigrant women living in the United States.

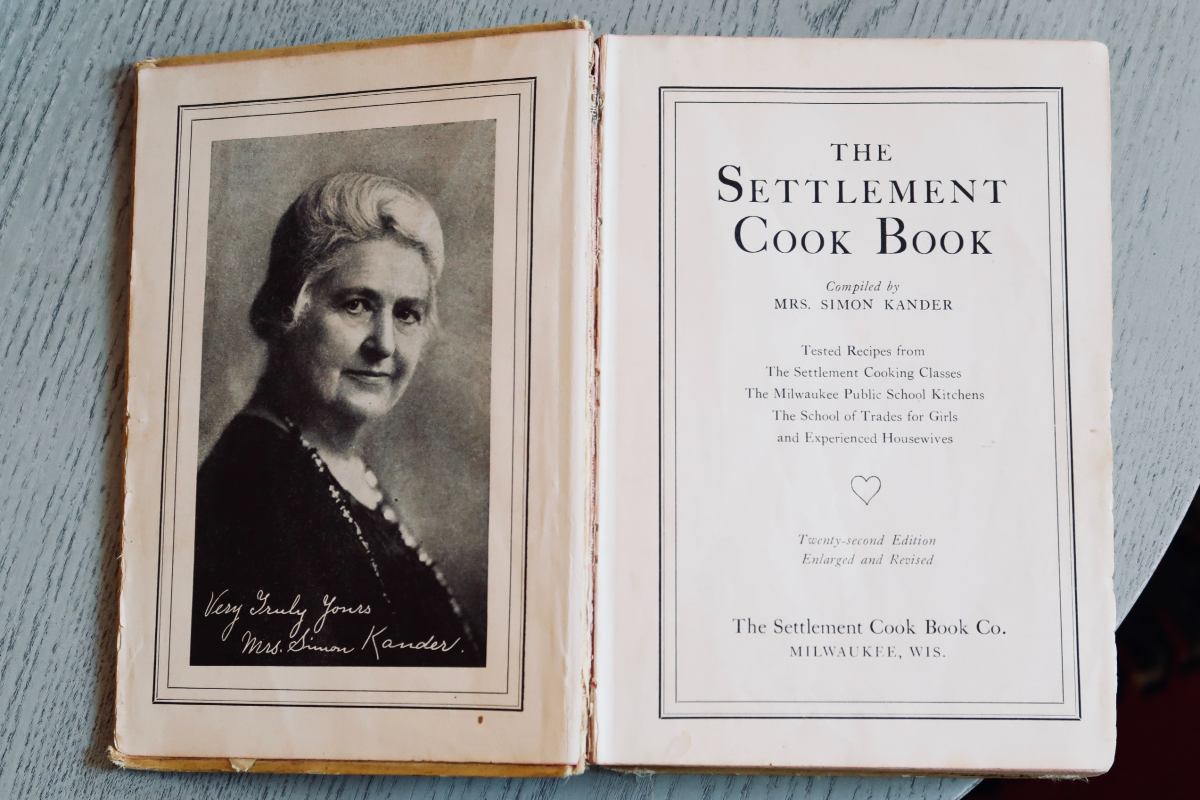

For the uninitiated, “The Settlement Cook Book” was originally published in 1901 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as a complete guide to how to cook, run a household and clumsily assimilate into American life as a recent Jewish immigrant. It was written by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Black Kander, a progressive philanthropist who, as part of the broader settlement movement, had founded The Settlement House, a social services organization for the waves of Jewish immigrants arriving in Milwaukee from Eastern Europe. The proceeds from the “Cook Book” funded the organization’s operations for nine years as well as its acquisition of and expansion to a new building, in a publishing fairy tale that sounds legitimately impossible but was a real thing that happened in 1910.

Every year, for 39 years, Lizzie revised and reissued editions of the “Cook Book,” all while getting elected as president of and running a rapidly expanding social services organization, teaching cooking and sewing classes to “Americanize” immigrant girls and educate them about nutrition, getting elected to the Milwaukee School Board (in 1907, a full 12 years before she could have voted for herself), successfully petitioning to open Milwaukee’s first girls’ trade school and running city-wide hunger and food exchange programs during World War I and the Depression. In short, she was a legend.

So it’s no wonder that when, on a recent Saturday night in Philadelphia, Abbie opened the door to her new apartment for the First Annual Settlement Cook Book Party, a photograph of Lizzie herself was hung from the doorway like a reverential cross between a presidential portrait and Jewish mistletoe.

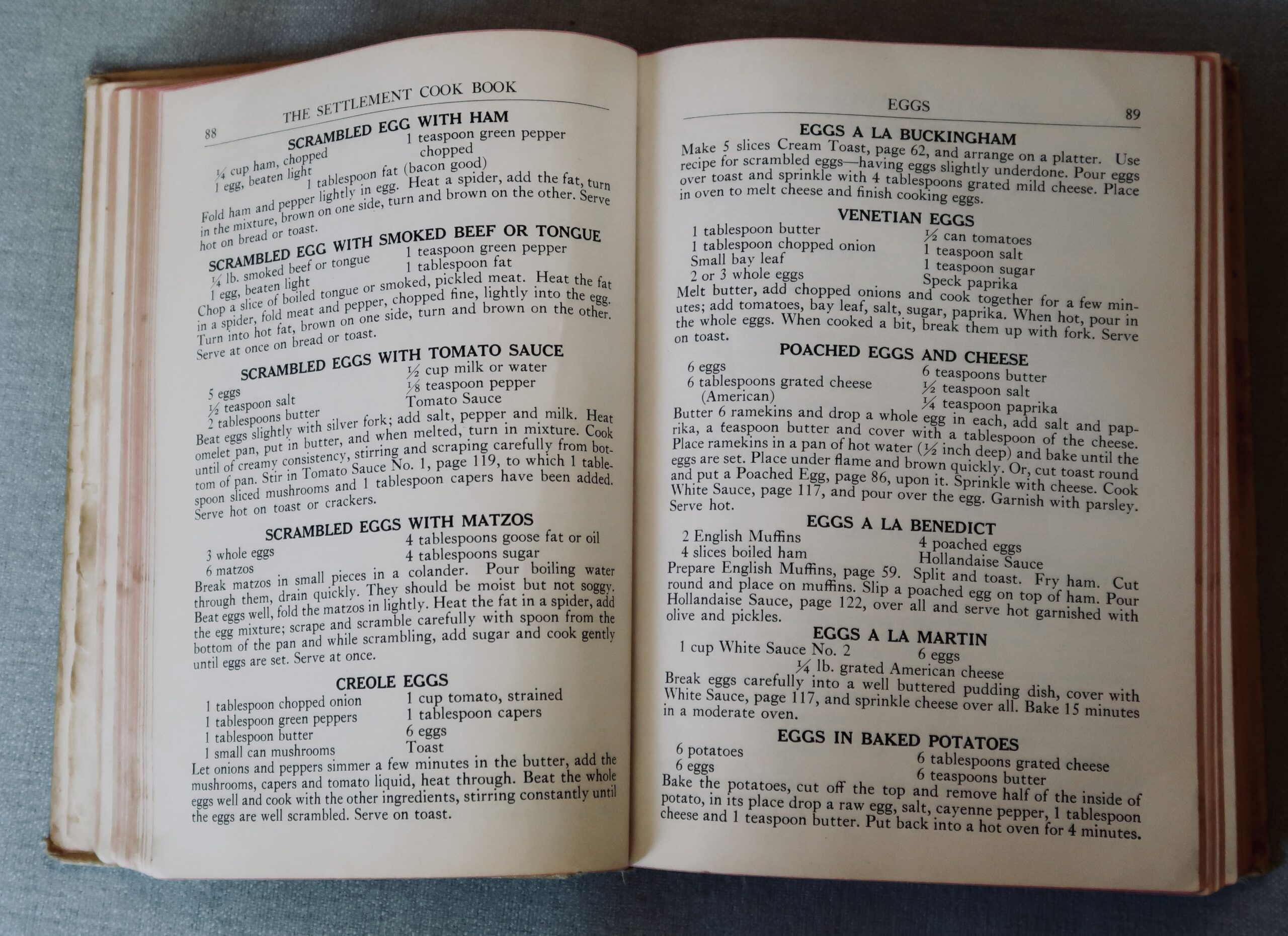

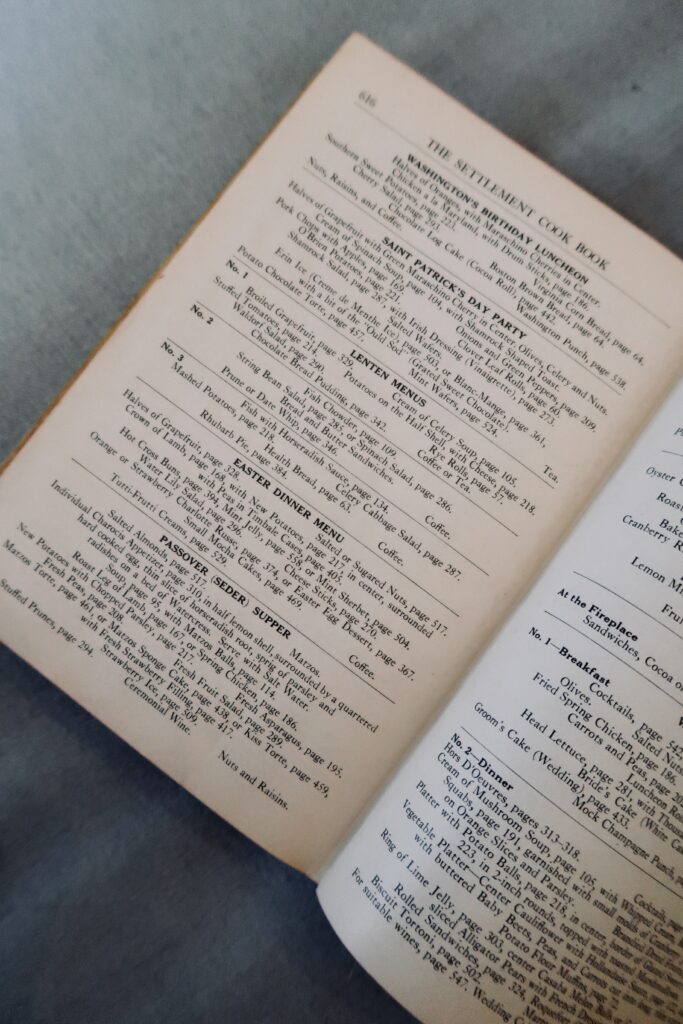

Abbie had decided to throw a party in honor of and in the style of the “Cook Book,” excited about uncovering and sharing this sliver of American Jewish history with friends. The book is “a trove of gems,” she says after I arrive, handing it to me and encouraging me to flip through it. It’s true: There are 40 different egg recipes, inspired by sloppily appropriated estimations of the other immigrant culinary traditions its author was exposed to. There is a section on the “Proper Care for Invalids,” which recommends fresh flowers daily, the use of dainty and delicate China, and the immediate removal of any leftover food from a “sick room.” There are thorough instructions for the use of an Electrical Toaster, a then-novel innovation in home cookery. And there is a self-conscious drive to enthusiastic assimilation, with recipes for Matzah Brei and Bacon And Eggs On Toast neighboring each other on a single page. In the back, there are recommended menus for various kinds of meals, from a Passover seder to a St. Patrick’s Day party.

To flip through “The Settlement Cook Book” is to feel the frantic attempt to be everything for everyone, absorbed and reissued as advice for Jewish immigrant homemakers. The book wants to be American, it wants to be Jewish, it wants to be elegant and refined, it wants to be heimish and it wants — needs — to be useful, above all. As a primary funding source for this organization meeting the basic caregiving needs of decades of Eastern European emigres arriving in desperate poverty, it needed both in content and in resulting demand to keep up with the crush of new information and immigration. And as a manual for running a household and, thereby, finding and retaining a husband, it was of critical importance to women who had few other opportunities for economic safety. It distills the deep fear about — and earnest desire for — assimilation and its requirements. This book was a how-to guide for American Hyphenate survival, anxiously pursued and guided by women on behalf of their families.

Abbie invited family and friends, both Jewish and not, from all over the East Coast to attend this party, dressed in their finest it’s-the-late-1930s-and-you’re-a-recent-American-immigrant garb. And friends turned out.

The costume directive was interpreted with wide variance. A few people showed up in (disappointingly) contemporary Saturday night outfits. One woman showed up dressed as Georgia O’Keefe, paint night prop included. Several men admitted to making last-minute thrift store excursions. Abbie wore the Tanya pie dress by Rachel Antonoff, of viral Pasta Puffer fame.

The snacks were more on-theme, drawing directly from the “Cook Book.” There was caviar and blini, lots of tinned fish, mayonnaise in almost every recipe, an “Ice Box Tiramisu Cake,” Milk Punch (recommended by Mrs. Kander for convalescents on soft diets despite being 50% booze) and a dairy jello mold that jiggled, untouched, for an uninterrupted six hours.

The foods followed the “Cook Book’s” lead: Some were visibly Eastern European, like the vile jello mold and hazelnut wafers from the local Russian grocery, unwrapped from packages illustrated with flowers and toddlers. Some were anxious Americanized hybrids, like dark rye bread with cream cheese and lox. Some were as imported and appropriated as the “Vietnamese Sweet Sauce” of Kander’s absolutely inaccurate imagination, like the Portuguese tinned fish we ate on Ritz crackers. Lizzie and her students at the Settlement House learned how to source the ingredients they needed to make matzah balls and flanken in the U.S., and contorted themselves into a taste for Cheese Tomato and Bacon Sandwiches. And it worked — well enough that we’re still doing the same thing all these years later, surrounded by friends whose grandparents and parents got similar support. It’s what we’ve been doing this whole time: mashing up what we know and what we’re open to trying into a smorgasbord of different flavors and combinations. “The Settlement Cook Book” happens to be Jewish, but it’s American through and through.

Also on the agenda for the evening? A competitive blind pickle taste test conducted by Abbie’s brother, in which seven different pickled foods were on offer and the shockingly difficult task involved correctly identifying the vegetable or fruit the participant was ingesting. The soundtrack, curated by a friend of the hostess and radio programmer of Philly’s WRTI classical music station, was heavy on Coleman Hawkins and Glen Miller. We played a viciously competitive round of Late 30s trivia in which we guessed the 10 most popular first names of the year (when in doubt, John is always correct) and were reminded of the Time magazine Person of the Year pick for 1938 (Adolf Hitler). The prize was a bag full of items that first hit the market in 1938 (Kraft Mac and Cheese! Lifesavers!) and the winner did an extravagant unboxing haul for the benefit of the crowd.

There was something sweetly uncanny about a party dedicated to a book that was so evidently successful and so thoroughly forgotten, at least among younger generations. Here we were: a mixed crowd of second and third generation immigrants, with heritage from Ashkenazi shtetls across Eastern Europe, but also from Italy, Cameroon, Colombia, Ireland, Poland, Peru and Pakistan. The Jews among us likely celebrate Easter far less than Lizzie would ever have imagined, and eat less bacon than her cookbook believed we might. We worked for startups, mixology bars, media companies, consulting firms, medical clinics. Not a single one of us — in particular the women — is interested in home making as more than a necessity or a skill to be deployed occasionally for the planning of an elaborate theme party. And all of this is true because of Lizzie and her peers: the mostly forgotten women who led the tremendous humanitarian effort of integrating thousands of impoverished and bewildered women, and by extension, their families, into a new homeland.

When Lizzie Kander originally asked the board of The Settlement for $18 to print the first run of the book, she was refused. She went on to scrape together the funding from local businesses for the first 1000 copies, which sold out within the year. In all, over 40 editions of “The Settlement Cook Book” were printed between 1901 and the 1970s (Joan Nathan has something like 20 of them in her collection), and over two million copies were sold, not including various reprints, spinoffs, and “The New Settlement Cook Book” published as a tribute in 1991.

Abbie thinks there are as many editions of this theme party in her future: with versions for various holidays (St. Valentine’s Day! Rosh Hashanah!) and times of year (A Cold Summer Picnic, a Lenten Feast) begging for air time. A brainstorm at the inaugural party had us scheming up a 1930s-style Charity Ball To Raise Collections for the Newly Emigrated. Lizzie would be proud, we hope.