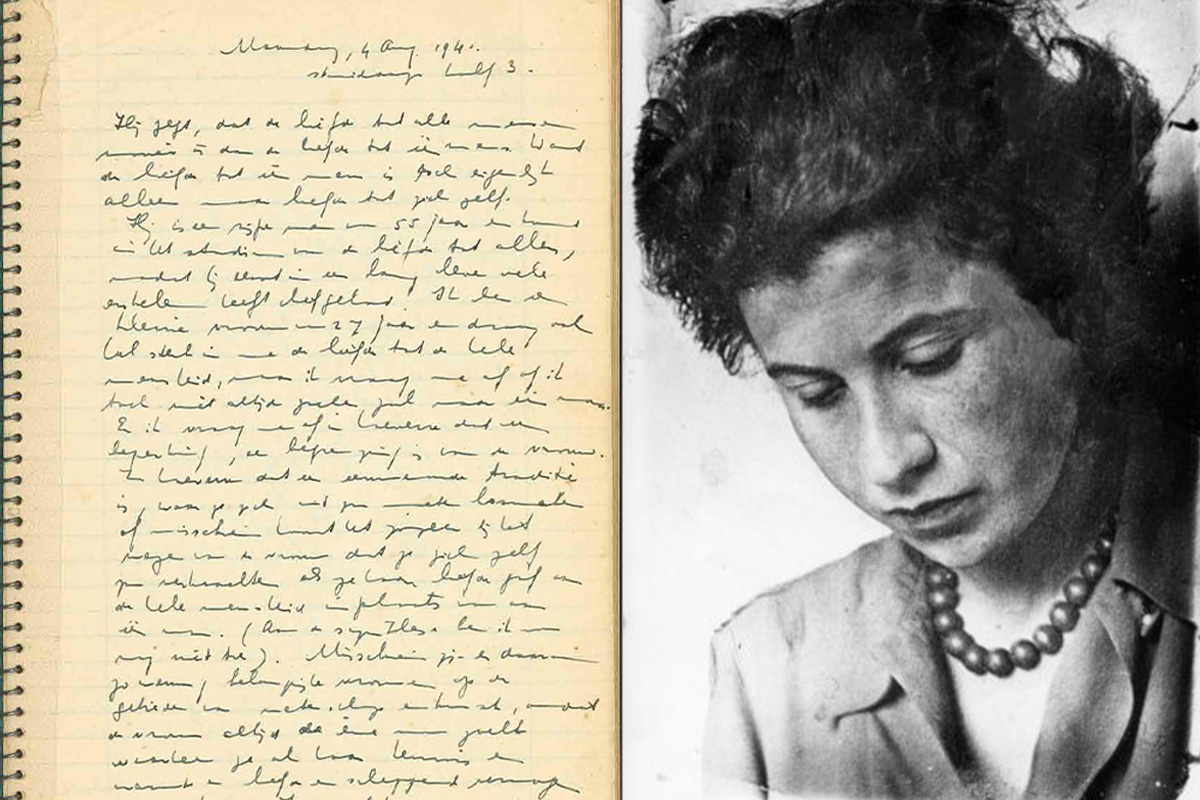

In small, neat cursive Dutch, on Sunday, March 9, in 1941, at a small desk in a room off of Gabriel Mesustraat in Amsterdam, Holland, a brilliant young Jewish woman began her first diary entry: “These thoughts in my head are sometimes so clear and so sharp and the feelings so deep, but writing about them comes hard.” The author, Etty Hillesum, started keeping a diary as a therapeutic exercise prescribed by her psychoanalyst and lover, Julius Spier (that he had terrible professional boundaries is an understatement).

In the pages that follow, Etty proved to be whip smart, unapologetic, an intellectual, self-assured and at the same time, insecure and frustrated with a life not yet fully lived and work not yet created. “The main difficulty,” she writes, “is a sense of shame. So many inhibitions, so much fear of letting go, of allowing things to pour out of me, and yet that is what I must do if I am ever to give my life a reasonable and satisfactory purpose. It is like the final, liberating scream that always sticks bashfully in your throat when you make love.”

I was 28 when I first read Etty’s diary, published in English as “An Interrupted Life” — just about the same age she was when she wrote it. Then, Etty was just about the same age as my grandmother, too, who was living in a flat on some other street in Amsterdam at that time. My grandmother had a sharp mind and a love of academia. She earned a law degree in Paris (one of two women in her class) and worked there in the field of Comparative Law before the war compelled her to join her father and two sisters, themselves escaping Germany, in the neutral Netherlands. A year and a half later, the country was occupied, and three years after that, her family was arrested and sent to the camps. She and one sister survived; her father and her other sister did not. I read Etty for a glimpse of who I imagined my grandmother had been before the terrible times that left an indelible stamp on trauma on her psyche. I wanted to know, too, who I would have been, what I would have done, had I been there. In my imagination, Etty and my grandmother unknowingly crossed paths somewhere along those cold, Dutch streets.

In the pages of her diary, Etty is alive. She meets up with an old boyfriend days before he marries and they share a kind of bittersweet goodbye to the relationship they once had. She reads Rilke, studies philosophy at the University of Amsterdam and tutors students in Russian. She has two boyfriends, Hans and Spier, and writes, “I don’t think I am cut out for one man….Nor could I be faithful to one man.” She dissects the events of each day. She has period cramps.

But the Nazi occupation of Holland begins to seep into the pages of Etty’s diary. In an entry from February, 1942, Etty describes the scene at the Gestapo Hall, where a crowd of Jews in Amsterdam have been corralled for questioning. She notes the behavior of a young, harried SS officer. When it’s her turn before his desk, he tries to put Etty in her place. “Wipe that smirk off your face!” he says. She tells him, “The smirk is my face.”

She analyzes the systems of fascism that have resulted in the Gestapo Hall: “despite all the suffering and injustice I cannot hate others…The terrifying thing is that systems grow too big for men and hold them in a satanic grip, the builders no less than the victims of the system, much as large edifices and spires, created by men’s hands, tower high above us, dominate us, yet many collapse over our heads and bury us.”

In another room in the same city, another diarist held fast to her perception of humanity’s goodness: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are good at heart.” While Anne Frank’s story has become the single story of the Holocaust, Etty Hillesum’s life and letters remain in relative obscurity. Anne Frank is palatable to a Christian audience already attuned to stories of martyred innocence and magnanimous forgiveness. Etty’s story, filled as it is with poly romance, philosophy, analyses of systems of power, and even an abortion, is no less important.

By 1942, Dutch Jews understood the violence that lay in wait for them at the end of the train track lines. Etty worked in the Dutch Jewish Council and, during that time, her diary takes on a tone of moral clarity.

She writes, “I feel as I were the guardian of a precious slice of life, with all the responsibility that entails. There are moments when I feel like giving up or giving in, but I soon rally again and do my duty as I see it: to keep the spark of life inside me ablaze.”

She might not have distributed leaflets or rose up against a guard or bombed a bridge, yet she shows us another method to resist fascism: refusal. Etty refused to extinguish her spark. She was generous to others and remained committed to what gave her joy: her friends, her studies, her Rilke.

From Westerbork concentration camp, she wrote to friends, “It is not easy — and no doubt less easy for us Jews than for anyone else — yet if we have nothing to offer a desolate postcard world but our bodies saved at any cost, if we fail to draw new meaning from the deep wells of our distress and despair, then it will not be enough. New thoughts will have to radiate outward from the camps themselves, new insights, spreading lucidity, will have to cross the barbed wire enclosing us and join with the insights that people outside will have to earn just as bloodily.”

Now 80 years and a couple generations removed from the Holocaust, we must make space to reveal unheard, more complex stories from that period. We need our ancestors’ stories, their writing, their art, their refusals, not only for a more complete history, but for our own survival.